|

The following is a Grad Paper and was written and submitted by Dave LaFontana of Harvard University, Massachusetts. A very big special thank you to Dave in allowing the Ottawa Beatle Site to e-publish his Grad Paper. Copyright by Dave LaFontana, July 10, 2003. First e-published by the Ottawa Beatles Site, October 30, 2003. All rights reserved. Photos presented below were used in his Grad Paper. |

You Say You Want a Velvet Revolution?

John Lennon and the Fall of the Soviet Union

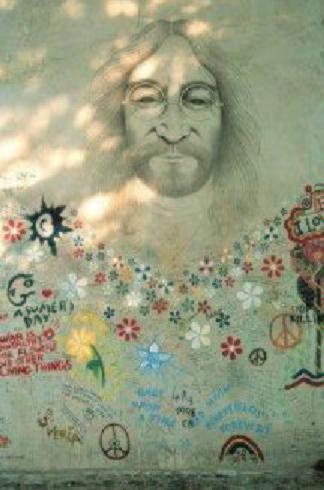

The Lennon Wall, Prague Czech Republic

(photo care of the “Bagism” website: http://www.bagism.com/ )

Dave LaFontana

History E-108/W

History of the 20th Century: 1951-2000

Grad Paper

July 10, 2003

Introduction

For a time during the Vietnam War, many Americans saw John Lennon as a threat. By 1968, the once-loveable mop top had morphed into a “New Left” revolutionary agitator, another “guerilla minstrel” the likes of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie. These radical folk singers in their time were considered—like Lennon was considered during Vietnam—a cultural force powerful enough to eventually pose a threat to the domestic stability of the US.

In America in the early 70s, many conservative Americans—including Strom Thurmond, Richard Nixon, and J. Edgar Hoover—considered (publicly at least) John Lennon’s radical leftist peace activism a subversive, communist-influenced force. A decade after J. Edgar Hoover warned against the Communists using “mass agitation” within “specialized fields: among women, among youth, among veterans, among racial and nationality groups, farmers, trade unions,1” Lennon and Yoko Ono were protesting on behalf of almost every group on the list.

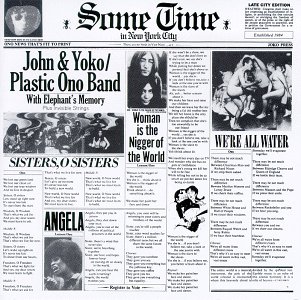

They declare themselves feminists, protest the Vietnam War, call for the release of imprisoned Black Panther Angela Davis, call for the release of imprisoned “White Panther” (and drug offender) John Sinclair, and demand that Britain “leave Ireland for the Irish,” all on one album alone 2. The fact that Lennon’s musical career with the Beatles gave him influence over American youth concerned many officials in the Nixon White House, since his fame would make him a powerful draw at politically charged anti-Nixon concerts and rallies before the 1972 election. Not surprisingly, the highly paranoid Nixon Administration (working through the FBI) eventually targeted Lennon for deportation. As funny as it may seem today, Lennon at this time was seen as—or at the very least treated as—a grave danger to the American way of life. However, hindsight has confirmed the opposite. John Lennon’s work—as a Beatle, with the Plastic Ono Band, and as a solo performer—has proven to be quite beneficial to western-style democracy and consumer capitalism in two distinct ways.

First and foremost, the music of Lennon and the Beatles was major triumph — both ideologically and commercially—for the West during the Cold War, a cultural explosion that not only triggered a demand for western products (like record albums, electric guitars, and blue jeans) by Soviet and Eastern European youths, but also bettered their perceptions of the West.

Secondly, Lennon was very much in line with the idea of “Socialism with a Human Face,” the idea of that was initially voiced by Czech leader Alexander Dubcek in 1968, and strongly influenced those in Gorbachev’s generation, a new breed of Communist leadership. Lennon’s message of peace and social justice in many ways matched, in some cases tested, and in one highly-important case—Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia—even influenced the concepts of Glasnost and Perestroika.

Lennon and the Beatles: a Threat to America?

Back in 1776

We fought the British then, folks.

Parents of America,

It's time to do it again, folks.

When they come back, here's how we'll begin,

We'll throw 'em in Boston harbor.

But please, before we toss 'em all in,

Let's take 'em to a barber.

|

- Lyrics from Allan Sherman’s 1964 novelty song “Pop Hates the Beatles" |

As the popular early 60s comedic singer Sherman satirized in his song “Pop Hates the Beatles,” not everyone in Britain and America loved the Beatles as much as the young people did. At the outset of Beatlemania, parents, politicians, members of the clergy, and other establishment figures worried that the morals of Western youth would be corrupted by the Beatles, and that the youth that flocked to the Beatles were no more than the “least fortunate of their generation, the dull, the idle, the failures” and a “fearful indictment of our educational system.3”

This was much as parents had worried ten years earlier about “Elvis the Pelvis.” But Elvis redeemed himself in the eyes of many parents in both Britain and America thanks to a two-year stint in the US Army in West Germany. By the end of the 60s, the Beatles—John Lennon in particular—had managed to alienate themselves even further from the American establishment: their hair got longer, their cloths got more outlandish and colorful, their drug use became obvious, and their music became more experimental (or even downright cacophonous). In Lennon’s case the message became radicalized. The American youth counterculture of the late Sixties was not entirely a product of the Beatles and the British Invasion—extended prosperity4 and the Vietnam War were the main causes—but popular culture and fashion were so changed by the musical phenomenon that it was easy for many older Americans to see it as such. For the World War II generation who had fought without question for their country—and had real fears of Communism knocking down countries like dominoes—the thought of subversive forces within their youth, working through drug-using “Hippies,” radical student activists, and left-leaning celebrities protesting a war against Communist North Vietnam was seen with real dread. Many feared that American youth culture was crawling with a “pink-tinged” infiltration of Communism in America.

The Beatles provided the soundtrack for the young generation, and from early on many American fundamentalist ministers and churchgoers had eyed them suspiciously. In 1966, Lennon had claimed that “Christianity will fade” and Beatles were “bigger than Jesus,” setting off anti-Beatle rallies and record burnings through the South and in places like Boston, eventually forcing him to apologize. “What have the Beatles said or done to so ingratiate themselves with those who eat, drink, and think Revolution?” asked David Noebel, author of a series of anti-Beatle tracts beginning in 1965. “The major value to the left in general…has been their usefulness in destroying youth’s faith in God.5” 1968’s “Revolution” raised eyebrows again. While Lennon did disavow Chairman Mao and anger many far left radicals by stating “count me out” of violent action, his message on one version of the song also said to count him “in;” he was remaining ambiguous on purpose since he hadn’t really made up his mind on it. American right-wingers complained about the song by arguing that Lennon and the Beatles were merely middle-of-the-road subversives warning the Maoists not to ‘blow’ the revolution by pushing too hard.6 Paul didn’t help the band’s standing in many people’s eyes by admitting publicly to using the dreaded LSD, as well as describing the band’s new company, Apple Corps (what could be thought of as an attempt at “People’s Venture Capitalism7”) “western-styled Communism” on The Tonight Show.8

As the Vietnam War dragged on, Lennon and Yoko Ono took their peace activism to more radical levels, having highly-publicized “bed-ins” in Amsterdam and Canada and recording songs like “Working Class Hero” and “Power to the People.” Lennon was soon considered a new “Guerilla Minstrel,” much in the vein of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, both of whom sang protest songs and were members—or were thought to be members—of the Communist Party.9

Lennon began to financially support the legal funds of controversial figures like Michael Abdul Malik, a.k.a. “Michael X,” a black Muslim radical from Britain who was eventually tried, convicted, and hanged in 1975 for the murder of two associates.10 He also began to publicly flaunt a leftist, sometimes downright Communist ideology. In a 1971 interview, Lennon complained that the class system of the west “hadn’t changed one bit,” and called on the middle class to “repatriate the people and get out of all that bourgeois shit.11” Even one of his most peaceful songs, “Imagine,” Lennon envisions a world with no religion, private possessions, or national boundaries, in other words a socialist, humanistic utopia.

But it was John and Yoko’s association with famous, or rather infamous members of the “New Left,” like Jerry Rubin, Rennie Davis, and Abbie Hoffman that got them unwanted attention from the federal authorities.12 Rubin, Davis, and Hoffman were all members of “The Chicago Seven,” and at least one—Rubin—was listed in FBI as an “Extremist” and “Key Activist.13”

By 1972, Lennon and Ono had released Some Time in New York City, an album containing songs protesting the imprisonment of radicals Angela Davis

and John Sinclair, the troubles in Northern Ireland, and women’s lib. The song “John Sinclair,” and Lennon’s participation in the 1971 Ann Arbor, Michigan rally protesting Sinclair’s imprisonment, would eventually lead President Nixon and the FBI to give Lennon and Ono special attention, investigating his anti-war activities, and trying to have him deported.14

The FBI classified Lennon as “Security Matter—New Left,” and later upgraded him to “Security Matter—Revolutionary Activities.15” In another FBI memo dated March 16, 1972, the New York branch office of the Bureau warned that Lennon was of a group that was planning “to coordinate New Left movement activities during this election year.” In the memo, a paragraph on New Left radical Stewart “Stu” Albert identified him incorrectly as associated with the Progressive Labor Party (PLP). The implication was clear: Lennon was associating with Communists.16

Hoover himself sent a memo on Lennon warning of his intentions of assisting in “organizing disruption of RNC [the Republican National Convention in San Diego, California, in August 1972].17” Hoover also mentioned Lennon in a memo to Nixon dated January 23, 1972 warning the President about Chicago Seven Defendant Rennie Davis’ future protest activities at the RNC.18

Even Lennon’s childhood hero, Elvis, didn’t trust him. During his visit to the White House on December 21, 1970, Presley told President Nixon that he was concerned for the youth of America, and feared that they had been seduced to drugs and immorality by the “filthy, unkempt appearance and suggestive music of the Beatles.19” He was unhappy that the Beatles were taking so much money out of America and back to England. Presley referred to them as “anti-American” accused them of saying “anti-American stuff when they got back [to England].20

+ + +

So, the question stands, was Lennon truly a Communist, hoping to knock down the American system? Those who knew him seem to think not. His radicalism seemed more naďve than sinister. Lennon was a product of the times, much as the rest of the counterculture. As many people close to him have said, Lennon felt guilty that he was a rich, privileged rock star, living a cushy life during turbulent times. Albert Goldman notes in The Lives of John Lennon that later in life, Lennon dismissed his radical period as something he dabbled in “more out of guilt than anything else. Guilt for being rich and guilt for thinking that peace and love isn’t enough, and you have to go and get shot or punched in the face to prove I’m one of the people. I was doing it [i.e. taking part in radical politics] against my instincts.21”

He was a also peace activist who realized that to succeed in his goals, he needed publicity, money, and a far-reaching medium—i.e. healthy sales of John and Yoko records, books, etc.—to work. At a press conference at the Ontario Science Center in promotion of the “John and Yoko Peace Festival,” Lennon was asked what got him started in the peace campaign. He answered by recalling getting a letter from filmmaker Peter Walkins, who told Lennon “People in our position have a responsibility especially to use the media for world peace.”

It’s not surprising that in a period of intense popular anger at the government, Lennon would call attention to himself as in line with the counterculture as it became increasingly radical. As cynical as it might sound, it sold records. Once his activities with the New Left became a liability to his personal interests (i.e. staying in America), Lennon and Ono backed off their political commitments “in a panic flight.22”

_________________________

In his

book The Love You Make: an Insider’s Story of the Beatles, Peter Brown,

the director of NEMS as well as Lennon’s best man at his wedding to Yoko,

referred to him as “just ripe for the far-left, publicity conscious brand of

politics,” and that Lennon was “by instinct part socialist, part right-wing

Archie Bunker; to be an indolent, wealthy rock star would have made him feel

guilty as sin, Yet the passionate politician he was to become was a phoney pose,

possessed with the guilty enthusiasm of a hypocrite.23” But Lennon was truly for peace in Vietnam

and women’s liberation, and regardless of his leftist leanings, he

never spoke out against Capitalism, in fact, he freely admitted to

using Capitalism to his own goals. At the Toronto press conference, Lennon

was asked how long he and Yoko were planning on leaving up their “War is Over”

billboards (like the one in New York City pictured at

right24). “We’d like to have as much money as Coca Cola and

Ford to be able to keep up [the “War Is Over” billboards]” he answered, “we

think advertising’s the game, and is the way to do it, and we’d like to have the

posters there all the time, and when you turn on the TV, they’re saying ‘Drink

Peace.’” He said of the song “Revolution” that even though he was dabbling with

the idea of socialism, he freely admitted playing the Capitalist

thing.25 He even jeered at his own hypocrisy when returning

his MBE to the Queen. In his note, he stated that he was returning it in protest

of Britain’s involvement in “the Nigeria-Biafra thing,” its endorsement of

America in Vietnam and that “Cold Turkey” was “slipping down the

charts.26”

Capitalism, in fact, he freely admitted to

using Capitalism to his own goals. At the Toronto press conference, Lennon

was asked how long he and Yoko were planning on leaving up their “War is Over”

billboards (like the one in New York City pictured at

right24). “We’d like to have as much money as Coca Cola and

Ford to be able to keep up [the “War Is Over” billboards]” he answered, “we

think advertising’s the game, and is the way to do it, and we’d like to have the

posters there all the time, and when you turn on the TV, they’re saying ‘Drink

Peace.’” He said of the song “Revolution” that even though he was dabbling with

the idea of socialism, he freely admitted playing the Capitalist

thing.25 He even jeered at his own hypocrisy when returning

his MBE to the Queen. In his note, he stated that he was returning it in protest

of Britain’s involvement in “the Nigeria-Biafra thing,” its endorsement of

America in Vietnam and that “Cold Turkey” was “slipping down the

charts.26”

Nixon probably didn’t really think Lennon was truly a Communist, but he did have a history of using Communism as a method for eliminating political enemies, such as he did during the 1950 California Senate race against progressive Democrat, feminist activist, and former actress Helen Gahagan Douglas, dubbed “the Pink Lady.” Former Beatle John Lennon working to mobilize the country’s youth to vote him out of office would definitely qualify him an enemy in Nixon’s eyes. Even the Feds’ own informants were not convinced he was truly a dangerous or subversive force. In a confidential informant report sent by the New York FBI office, the informer makes a significant statement that an unnamed person “had numerous conversations with John Lennon and his wife about becoming active in the New Left movement in the United States and that Lennon

and his wife seemed uninterested…Lennon and his wife are passé about United States politics.27” In another report, an FBI confidential informant reported that Lennon said he would participate in demonstrations at the Republican National Convention only “if they are peaceful. 28”

Meanwhile, Back in the U.S.S.R…

“Don’t be such a ‘bitels’”

My papa tells me

My mama, like my mama says:

”To the barber go!

’cause the barber’s running

after you with scissors.

Cut off your shaggy hair!

Shame on you son, shame!”

- Lyrics from popular Polish singer

|

Czeslaw Nieman’s mid 1960s novelty song “Don’t Be such a Bitels29” |

As we discussed in class during the semester, during the Cold War both the Western and Soviet societies tended to mirror one another’s trends and fears. The west had McCarthyism; the east had Zhadovism, for example.30 And not surprisingly, this phenomenon showed itself in the appearance of both a Western and Eastern counterculture. Just as singers like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez were condemning racism and injustice in coffeehouses in America, West German-born singer Wolf Biermann was criticizing Stalinist East German ideologues, and the Berlin Wall.31 And, while Beatlemania was turning western fashion trends and pop culture on its ear, it was doing the same in the Eastern Europe and eventually the Soviet Union. Official and parental reaction to the counterculture upheaval Beatlemania brought in its wake was no different than their western counterparts. But the sinister, subversive powers corrupting the youth were feared by the Soviets to be a tool of the Capitalistic, decadent, imperialist west. Krokodil (Crocodile), an all-Union satirical magazine, compared the Beatles with U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater - an insult in the then USSR. 32

Western authorities were not only leery of rock music and the counterculture left, but also the influence of older college professors they feared were using their influence in the classroom to destroy the American system from within. Eastern authorities were likewise worried about western jazz and rock and roll, western influences on the young “hooligan” counterculture, but also the more liberal minded authorities in Bloc countries like Poland and Czechoslovakia they feared were using their influence to destroy the Soviet system from within.

Leaders like Alexander Dubcek in Czechoslovakia had granted the people of his country more freedom from censorship, facilitated the spread of western music, jazz or rock and roll, within the USSR.

+ + +

The Beatles are a very early example of Globalization: a cultural phenomenon that affected youth in every corner of the world. The Beatles learned American music in England, honed their skills by playing for American, British, and German audiences in Hamburg, and proved to American record executives that the US no longer cornered the market on big musical acts. Through the Beatles, American-style rock music and the youth counter-culture that went along with it made its way behind the Iron Curtain in a huge way. Soviet parents, much like their American and British counterparts, scratched their heads in bewilderment at their children's love of British rock 25 years before the wall fell.

The Beatles were far from the first western music heard in the Soviet Union. Western popular culture made its first real headway in the form of American Jazz immediately following World War II. In the 50s, Elvis, Bill Haley, and Chubby Checker and the Twist also made their way into the USSR. But not even Elvis Presley got the reaction that the Beatles got.

As Ryback writes in Rock Around the Bloc, during the 1950s, young people around the Soviet Empire had their own western-influenced fads and fashions: Russian stiliagi hung out around Gorky Prospekt in Moscow; The Czech pásek hung out in Wenceslaus Square, pinned American cigarette labels to their ties and chewed paraffin wax (in lieu of Western-styled chewing gum). Poland had the bikiniarze. Hungary had the jampec.33 The Eastern European and Soviet Youth who embraced the Beatles after 1964 differed than those who had danced to the music of Bill Haley and Elvis Presley in 1956 because “Beatlemania swept away many of the national and social distinctions. The Beatle look became de rigueur. In the Soviet Union, Beatle fans wore jackets without lapels called bitlovka. In Poland, bitels, as Beatles fans became known, sported Beatles buttons sent by relatives in the West. In Budapest Hungarian Beatles fans cut their hair into Beatles-frizura, tailored their coats into Beatles-kábat, and proudly pounded the streets in boots they dubbed Beatles-cipö.34”

Many Eastern European and Russians writers who grew up behind the Iron Curtain concur with this sentiment. The book Strings for a Beatle Bass: The Beatles Generation in the USSR is a fascinating first-hand account of growing up a Beatle fan in the USSR, and its author, Dr. Yury Pelyushonok35 recalls how the name ‘Beatly’ made it to the Russian lexicon even before the music did (basically meaning western-influenced music). He also reminisced about hearing Can’t Buy Me Love played as background music in a Soviet documentary about the decadent Capitalist West. The song had been picked by the producers as “an example of something disgusting, noisy, and bourgeois.” The effect on the audience, however, was the opposite, and the kids would gather around the courtyard to listen to the song coming from the apartment window of one lucky enough to have a TV.36

As Trey Donovan Drake writes in The Historical Political Development of Soviet Rock Music, “their [The Beatles’] style inspired the Soviet rockers to form what they called ‘beatle bands.’ Alexander Gradsky was one of the leaders of a beatle band, whose uncle danced in the Moiseev Ballet company…His uncle brought him Beatles records from abroad which ‘put him in a state of shock...everything except the Beatles became pointless.’ It was no longer an expression of trendiness or snobbery-fans repaid the Beatles in kind for the sincerity they felt in their music.”

In a 1996 Kiev Post article titled “Communism Destroyed,” Alexander Zheleznjak writes, “Their names were John, Paul, George and Ringo. The Four that destroyed Communism inside of me. And it was loooong [sic] before ‘glasnost’ and ‘perestroika.’ It was even long before Leonid Brezhnev announced that we had built ‘developed socialism’ in the Soviet Union…The first Beatles’ song I heard was ‘A Hard Day’s Night.’ It was a revelation. It was so beautiful and so clear that I, a naive teenager, thought everyone listening to the song must feel the same way. Then came their other songs and, step-by-step, I turned into a fan of the group.”

In an article titled “You Say You Want a Revolution” published in the August 2003 issue of History Today, Mikhail Safonov (senior researcher at the Institute of Russian History at St Petersburg) gives another first-hand account of the Beatle’s influence on his generation. He writes “The name of [Mark David] Chapman has become linked with that of Lennon, as other murderers are connected to their victims: Brutus and Caesar, Charlotte Corday and Jean-Paul Marat. Paradoxically, Lennon himself can be linked with the name of the Soviet Union in just the same manner. It was Lennon who murdered the Soviet Union.”

“He did not live to see its collapse, and could not have predicted that the Beatles would cultivate a generation of freedom-loving people throughout this country that covers one-sixth of the Earth. But without that love of freedom, the fall of totalitarianism would have been impossible, however bankrupt economically the communist regime may have been…the music came to us from an unknown, incomprehensible world, and it bewitched us.37”

As Reuters reported on May 24, 2003, while Paul McCartney was touring Russia, he heard a similar story from the current Russian president: The story reads “President Vladimir Putin has told Paul McCartney the Beatles, hugely popular in Soviet times despite being frowned on as propagandists for an alien ideology, had been a breath of fresh air for Russians.” “‘It was very popular, more than popular,’ Putin said when asked whether he had listened to the Beatles when contacts with Western pop music were discouraged. “It was like a breath of fresh air, like a window on to the outside world.”

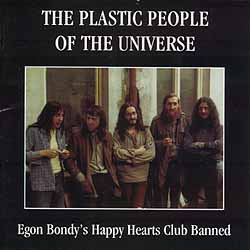

In his

March 1996 article on the Czech band “The Plastic People of the Universe” (more

on them later), Joseph Yanosik wrote that “the story [of the Plastic People of

the Universe] begins, of course, with the Beatles and 1964 (the Beatles’

influence was seen clearly in the title of the Plastic

People’s album,  Egon

Bondy’s Happy Hearts Club Banned,

pictured at right38). It is imperative to

understand that Beatlemania was not an isolated event limited to America and the

United Kingdom. Young people throughout Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union had

their lives changed by John Lennon and the Beatles. Since the beginning of the

Cold War, kids from the eastern side of the Iron Curtain had hungered for all

things American as an escape from their cultural isolation. American jazz had

served this purpose in the late 1940's through the fifties. The gates were then

kicked open by Elvis and Bill Haley, but it was the Beatles who brought down the

wall.”

Egon

Bondy’s Happy Hearts Club Banned,

pictured at right38). It is imperative to

understand that Beatlemania was not an isolated event limited to America and the

United Kingdom. Young people throughout Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union had

their lives changed by John Lennon and the Beatles. Since the beginning of the

Cold War, kids from the eastern side of the Iron Curtain had hungered for all

things American as an escape from their cultural isolation. American jazz had

served this purpose in the late 1940's through the fifties. The gates were then

kicked open by Elvis and Bill Haley, but it was the Beatles who brought down the

wall.”

+ + +

But what might have been even as important for the West than the ideological victory was the fact that rock and roll and western pop culture created a demand for western products. Since LP versions of records were confiscated by the Soviet authorities, resourceful music fans used X-ray plates, flexi-discs, and if they were privileged enough, tape recorders (with the help of radio DJs playing entire albums uninterrupted so they could be recorded). But these pirated copies were of very poor quality. To follow the fashion of their idols, blue jeans were equally in demand. A thriving black market provided young people with records, instruments, and jeans smuggled-in from the West. Eventually, the Soviet authorities saw the financial gains in creating official Vocal Instrument Ensembles, or “VIAs” and releasing officially authorized releases of Russian rock groups, and even of some Beatles singles. In short, the Beatles spawned a cultural revolution that can be thought of as “creeping Capitalism.” Even though they were Soviet ‘beatle’ bands popping up all over Russia and Eastern Europe, there were practically no Soviet-made guitars until 1965. “Many groups were forced to make their own instruments or purchase copies of Western guitars that were produced by unofficial manufacturers. One of these manufacturers in 1969 managed to publish in a popular mechanical magazine a technique of converting an acoustic guitar into an electric one using a telephone voice coil, and shortly thereafter there were reportedly no functioning public telephones in all of Moscow. Such activities only called more attention to the growing youth cultural trends, and would cause the Soviet officials from time to time to call for anti-rock action. 39”

And, in hindsight, although both sides were caught up in the paranoia of the era, the Soviet officials’ fears turned out to be right. A generation of young people across national boundaries—on both sides of the Iron Curtain—were sharing a common ground with each other in the form of rock and roll music. This shared cultural experience and the message of “All You Need is Love” provided young people in Soviet Bloc countries with a reason to not fear the people that they had always been told were their enemy. It also planted the notion that the Communist authority, not the Imperialist west, was the actual barrier between themselves and happiness.

As acclaimed Czech director Milos Forman said the Beatles brought down the communism that caused him to spend most of his life in the US…It has long been an argument that teenagers' desire for blue jeans and western music brought down the Iron Curtain. But Forman maintained it was actually the regime's criticism of the “fabulous” Beatles that punched a hole in their own credibility. “Suddenly the ideologues are telling you this is decadent, these are four apes escaping from the jungle. I thought I'm not such an idiot that I love this music and suddenly these political ideologues were strangers.40”

In “You Say You Want a Revolution,” Safonov writes “the more the authorities fought the corrupting influence of the Beatles - or ‘Bugs’ as they were nicknamed by the Soviet media (the word has negative connotations in Russian) - the more we resented this authority, and questioned the official ideology drummed into us from childhood…the history of the Beatles' persecution in the Soviet Union is the history of the self-exposure of the idiocy of Brezhnev's rule. The more they persecuted something the world had already fallen in love with, the more they exposed the falsehood and hypocrisy of Soviet ideology.41”

Even when the Beatles songs were officially released, Safonov writes “all the songs were named correctly, but they were credited to "a vocal-instrumental group" - rather as if A Hero of our Time were published in England, but instead of MY Lermontov's name, the publisher put simply “a writer. It was these details that forced eople to feel the full inhumanity of the regime. Why did the communists persecute the Beatles to such an extent? Deep down, the communists felt that the Beatles were a concealed and potent threat to their regime. And they were right. Beatlemania washed away the foundations of Soviet society because a person brought up with the world of the Beatles, with its images and message of love and non-violence, was an individual with internal freedom. Although the Beatles barely sang about politics (our country was directly mentioned only once in their repertoire, in Back in the USSR), one could argue that the Beatles did more for the destruction of totalitarianism than the Nobel prizewinners Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Andrei Sakharov. 42”

+ + +

This resentment towards Soviet authorities who would put down western rock and roll is very important because of the before mentioned Plastic People of the Universe. In his 1996 article, Yanosik wrote “The Plastic People were ultimately a major catalyst to the overthrow of communism in Eastern Europe. History would most surely have been very different without them. Apart from the aforementioned Beatles and the Velvet Underground, there's not a lot of rock and roll bands you can say that about.”

Yanosik writes this about the Plastic People because of their role as the origin for the creation of Charter 77, the human rights document that would bring rock and roll fan43 and playwright Vaclav Havel into the world of politics. The band was formed after the brief explosion of pop culture that came in the 1968 Prague Spring with Alexander Dubcek's liberalization of communism. Mirroring their Western long-haired contemporaries, for a while the much abused peace, love and freedom ethos of the hippy culture actually meant something more than annoying people with short hair.44 It was their arrest in 1976 on trumped-up charges of “disturbing the peace” that galvanized Czechoslovakia's leading artists, writers and intellectuals—including Havel—to draw up Charter 77. In May, 1986, the dissident playwright told a British journalist that Havel political change was coming in Czechoslovakia—not from above but from below, from what he called “the fifth column of social conscio usness.45” Havel knew what the Czech people knew: the nation that claimed Milan Kundera, Franz Kafka and President playwright Vaclav Havel believed that words are tantamount.46 How appropriate that the man who would eventually reach the presidency of a formerly repressive Communist country after the peaceful Velvet Revolution of 1989, a man with such strong roots in the 60s counterculture movement, would be a native Bohemian.

In his book Open Letters: Selective Writings, 1965-1990, Havel explained the importance of the Plastic People, rock and roll, and Charter 77 to the history of his country:

|

UNDENIABLY, the most important political event in Czechoslovakia after the advent of the Husak leadership in 1969 was the appearance of Charter 77. The spiritual and intellectual climate surrounding its appearance, however, was not the product of any immediate political event. That climate was created by the trial of some young musicians associated with a rock group called “The Plastic People of the Universe.”

Their trial was not a confrontation of two differing political forces or conceptions, but two differing conceptions of life. On the one hand, there was the sterile Puritanism of the post totalitarian establishment and, on the other hand, unknown young people who wanted no more than to be able to live within the truth, to play the music they enjoyed, to sing songs that were relevant to their lives, and to live freely in dignity and partnership. These people had no past history of political activity. They were not highly motivated members of the opposition with political ambitions, nor were they former politicians expelled from the power structures. They had been given every opportunity to adapt to the status quo, to accept the principles of living within a lie and thus to enjoy life undisturbed by the authorities. Yet they decided on a different course. Despite this, or perhaps precisely because of it, their case had a very special impact on everyone who had not yet given up hope. Moreover, when the trial took place, a new mood had begun to surface after the years of waiting, of apathy and of skepticism toward various forms of resistance. People were “tired of being tired”; they were fed up with the stagnation, the inactivity, barely hanging on in the hope that things might improve after all. In some ways the trial was the final straw. Many groups of differing tendencies which until then had remained isolated from each other, reluctant to cooperate, or which were committed to forms of action that made cooperation difficult, were suddenly struck with the powerful realization that freedom is indivisible. Everyone understood that an attack on the Czech musical underground was an attack on a most elementary and important thing, something that in fact bound everyone together: it was an attack on the very notion of living within the truth, on the real aims of life. The freedom to play rock music was under stood as a human freedom and thus as essentially the same as the freedom to engage in philosophical and political reflection, the freedom to write, the freedom to express and defend the various social and political interests of society.

People were inspired to feel a genuine sense of solidarity with the young musicians and they came to realize that not standing up for the freedom of others, regardless of how remote their means of creativity or their attitude to life, meant surrendering one's own freedom. (There is no freedom without equality before the law, and there is no equality before the law without freedom; Charter 77 has given this ancient notion a new and characteristic dimension, which has immensely important implications for modern Czech history. What Sladecek, the author of the book Sixty-eight, in a brilliant analysis, calls the “principle of exclusion,” lies at the root of all our present-day moral and political misery. This principle was born at the end of the Second World War in that strange collusion of democrats and communists and was subsequently developed further and further, right to the bitter end. For the first time in decades this principle has been overcome, by Charter 77: all those united in the Charter have, for the first time, become equal partners. Charter 77 is not merely a coalition of communists and noncommunists-that would be nothing historically new and, from the moral and political point of view, nothing revolutionary-but it is a community that is a priori open to anyone, and no one in it is a priori assigned an inferior position.) This was the climate, then, in which Charter 77 was created. Who could have foreseen that the prosecution of one or two obscure rock groups would have such far-reaching consequences?47 |

Havel’s concept of “Power to the Powerless” was very much in line with Lennon’s ideas of “Power to the People.48” The utopian ideas that Lennon spoke about, such as peace, justice for the working class, and socialist democracy was basically the same ideas of “Socialism with a Human Face,” the idea brought about by Alexander Dubcek and later Mikhail Gorbachev. These new Communist leaders of Soviet Union saw hope in the idea of socialism, but saw the dire need for reform of the old totalitarian ways of the Party.

And so did John Lennon. In February 1972, when being interviewed by Alan Smith for Hit Parader magazine, Lennon states that “they [members of the American and British Establishment] knock me for saying 'Power To The People' and say that no one section should have the power. Rubbish. The people aren't a section. The people means everyone…I think that everyone should own everything equally and that people should own part of the factories and they should have some say in who is the boss and who does what. Students should be able to select teachers…It may be like communism but I don't really know what real communism is. There is no real communism state in the world—you must realize that Russia isn't. It's a fascist state. The socialism I talk about is ‘British socialism,’ not where some daft Russian might do it or the Chinese might do it. That might suit them. Us, we'd rather have a nice socialism here...”

+ + +

When Lennon was assassinated on December 8, 1980, both American and Soviet leaders called him a hero and both sides praised his memory. “The bitter irony of this tragedy,” mourned Komsomolskaia pravda two days later, “is that a person who devoted his songs and music to the struggle against violence has himself become its victim.49” After his assassination, grieving fans in Prague and Sofia both created “Lennon Walls” as memorials to the fallen Beatle, which came to represent not only a memorial to Lennon and his ideas, but also a monument to free speech and the non-violent rebellion of Czech youth against the repressions of neo-Stalinism.

In his excellent essay on the Lennon Wall in Prague, Ron Synovitz writes “as John Lennon's ideals for peace thrived under totalitarianism at Prague's 'Lennon Wall' and helped inspire the non-violent “Velvet Revolution” that led to the fall of Communism in the former Czechoslovakia.”

“Shortly after Lennon's death in 1980, under the ever-watchful eyes of the Communist secret police, an anonymous group of Prague youth set up a mock grave for the ex-Beatle. The event was spontaneous, much in the same way that fans in New York City had gathered at Central Park upon hearing of Lennon's death. But unlike the gathering in New York, mourners in Prague risked prison for what authorities called “subversive activities against the state.”

“The Wall quickly took on a political focus and, inevitably, developed into a forum for grievances against the Communist state. Lennon marches also started to take place each year on Dec. 8. Those marches ultimately became linked to dissident protests on International Human Rights Day -- December 10.

Participants in those early marches say they were channeled through a gauntlet of uniformed and plain-clothes police. Many were jailed or beaten for joining the marches50.”

Ryback writes about the Sofia Lennon Wall, which was also an important political forum because an incident there that served as the first test for Bulgarian style glasnost :

|

On December 8, 1986, ten high-school students from class 8C of the Dimitur Polyanov High School solemnly paraded through the streets of the Bulgarian capital bearing a wreath they intended to place at Sofia's unofficial Lennon Wall, the facade of the city's notary building located in the Ignatiev Street. When the procession arrived at the memorial, one of the youths wrote on the `wall in English: “John, you are in our hearts.” The police appeared minutes later and apprehended the fourteen year olds. Following an interrogation at the ', police station, the youths were released and their families each fined two hundred leva.

A letter was subsequently sent to schools and factories in Sofia warning officials to be on the lookout for “spontaneous youth groups under foreign ideological influence.” Almost immediately, a response appeared in the city paper Pogled defending the students and criticizing officials for having reacted with such harshness to a peaceful tribute to John Lennon. A public debate quickly emerged in the pages of Pogled. Panayot Bonchev, the district's deputy chairman of the People's Council, defended the government actions. He criticized the youths' practice of organizing themselves into unofficial groups and also leveled criticism against the deceased former Beatle. “John Lennon,” wrote Bonchev, “was only 20% a fighter for peace and 80% the product of Western democracy. “Bonchev's letter infuriated Lennon fans. Pogled received over two hundred letters of protest, mostly from young people defending the actions of the ten students and condemning the “incompetence and insensitivity” of government officials. One protester, responding to Bonchev's assessment of Lennon, suggested the ten students may have avoided arrest had they written: “John, we love only 20% of you.”

On January 27, 1987, Todor Zhivkov seemed to tilt the scales against government hard-liners when, in the spirit of glasnost, he urged public criticism of inefficient government organizations and ministries. Rock-music supporters rallied. On March 25, 1987, Uchitelsko delo, the educators' newspaper, demanded more television and radio exposure for rock music to overcome the air of “stagnation” lingering on the official music scene. In April 1987, Dimitr Spasov, a specialist on youth policy, wrote an article in Pogled calling for public tolerance of Bulgaria's punk rockers, heavy-metal fans, and disco fans. Spasov praised punk rockers for their outrageous appearance, for despising duplicity and falsehood in personal relationships, for ridiculing stereotyped behavior. Rather than considering punk and other forms of rock and roll a “disease of socialism,” Spasov argued that this music offered an opportunity to purge society of many ills.

The Communist youth daily Narodna mladezh and the student paper Studentska tribuna began writing prolifically about rock music. In May 1987, Bulgaria sponsored its first official rock festival, Rokfestival '87. 51 |

The Prague Lennon Wall continued to be a force for democracy in the years leading up to 1989. As Synovitz writes “the threat of prison couldn't keep people from slipping into [Wenceslas] square at night to scrawl graffiti epitaphs in honor of their underground hero. The Communist police tried repeatedly to whitewash over the graffiti but they could never manage to keep the wall clean. Paintings of Lennon began to appear along with lyrics of his songs. The wall quickly took on a political focus and, inevitably, developed into a forum for grievances against the Communist state. Even the installation of surveillance cameras and the posting of an overnight guard couldn't stop the opinions from being expressed.52”

+ + +

On Nov. 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell. Days later in Czechoslovakia, the peaceful revolution continued in the form of popular, but peaceful, rallies. In an article on Havel in January 2003, writer Ondrej Hejma wrote “a rally on the morning of Friday, Nov. 17 seemed routine enough. But at dusk, as some 10,000 people marched toward Wenceslas Square, police cracked down hard. Hundreds were injured. ‘You have lost already,’ demonstrators chanted the next day, and the next, gradually swelling to a crowd of hundreds of thousands. In a couple of weeks, it was all over. The Iron Curtain was being rolled up, and on Dec. 29, Havel stood before a parliament still dominated by communist holdovers and laid out his hopes of becoming the country's first democratic president in half a century. “I promise not to let you down,” Havel said in his nomination speech, pledging fair and free elections. And free they were - almost absurdly so. Rock stars Frank Zappa and Lou Reed were among those helping a motley crew of bohemians to mount an election campaign. As the Soviet army began leaving, the Rolling Stones arrived. ‘The tanks are rolling out, the Stones are rolling in,’ posters proclaimed. Havel had won - and the communists were finished.53”

Conclusion

What marked the end of the August 1991 day that saw the collapse of Communism in the

USSR? a) a military parade on the Red Square, or b) a huge, open-air rock 'n' roll

concert in Moscow, organized by the defenders of the White House.

Should there be any difficulties in answering this question, Keith Richards can provide a

hint: “After those billions of dollars, and living under the threat of doom, what brought it

down? Blue jeans and rock 'n' roll.”

|

- Closing lines of a letter from Dr. Yury Pelyushonok to the London Guardian dated December 2, 2000 |

Did the Sixties Counterculture that Lennon represented really change America? In many ways, yes, but in the way that Nixon, Hoover, and others feared, i.e. violent revolution, falling dominoes, and the birth of a “Soviet America,” it most definitely did not.

On October 10, 2001, MTV news reported that “The Beatles may have been the most powerful rock band of 2001 thanks to their hits package 1…The Fab Four ranked third on the power list—behind Tom Cruise and Tiger Woods—with earnings of $70 million for the year.54” On March 11, 1997, the Queen of England knighted Paul McCartney. Fellow 60s rabble-rouser Mick Jagger was given the same honor on December 12, 2003. At the turn of the century, The Beatles were still a Capitalistic, moneymaking machine, and Britain's rebel youth of the 60s had become their old guard. 55

But the same cannot be said for the Soviet Empire. The inundation of Western culture and the message of peace forever changed the generation. As frivolous as it seems, a cultural force like music can be very powerful, and Russia in particular has a history of using the arts as a vehicle for social change. During Imperial Russia, Russian intelligentsia used works of fiction, like Eugene Onegin and What is to Be Done? to

protest the repressive tsarist regime. During the Soviet regime, they used rock and roll.56 Rock and roll served as a lightning rod for the demand for cultural freedom, and an all important symbol of that freedom. The Beatles legacy in Russia could very well be that The Lennon Wall brought down the Berlin Wall.

_________________________

1 Hoover, J. Edgar, “The Communist Trojan Horse in Action,” pp. 197-8, Masters of Deceit: the Story of Communism

in America and How to Fight It.

2 Some Time in New York City, released in 1972

3 Johnson, Paul. “The Menace of Beatleism.” The New Statesman, 28 February 1964

4 Unger, Irwin and Debbie, The Times They Were a Changin’: the Sixties Reader, pp. 150, “The counterculture, even

more than the political New Left, was the child of prosperity. Hippies renounced the bourgeois rat race of nine-to-five

jobs, manicured suburban lawns, and prudent lives. Some professed to despise private property and possessions in

general, but most of them came from this very milieu. Almost all were white suburban dropouts who lived off the

surplus and cast-offs of an affluent society. Some were straight remittance men and women who survived on checks

sent by Dad and Mom from home.”

5 Wiener, Jon, Come Together, pp.12

6 MacDonald, pp. 227

7 At a press conference in New York City to announce the formation of Apple, Lennon described the new company to

the press: “It's a business concern, records, films, and electronics, and as a sideline, manufacturing, or whatever it's

called. We want to set up a system whereby people who just want to make a film about anything don't have to go on

their knees in somebody's office.”

8 Brown, Peter, pp. 303.

9 Seeger joined the Communist Party in 1942; Hampton, pp. 95 “According to Gordon Friesen, who knew Guthrie in

New York in the 1940s, [Guthrie] was indeed a card-carrying [Communist] party member... ‘a full-fledged member of

the Village branch of the Communist Cultural Section.’”

10 Giuliano, Lennon in America, pp. 36: “[Michael X] was a highly controversial character, either a peace loving martyr

for the black movement (according to Dick Gregory) or a cold-blooded killer (according to Tariq Ali). Lennon funneled

considerable funds into Michael’s legal defense and supported him personally until the very end.”

11 “Power to the People: John Lennon and Yoko Ono talk to Robin Blackburn and Tariq Ali,” originally published in

the Red Mole 8-22 March 1971; in this interview, Lennon also expressed interest in traveling to Yugoslavia to see a

society under workers’ control, and that he read the Communist newspaper The Morning Star “to see if there’s any

hope.”

12 In his 1970 book J. Edgar Hoover Speaks Concerning Communism, Hoover referred to the New Left as “a firmly

established subversive force dedicated to the complete destruction of our traditional democratic values and the

principles of free government. This movement represents the militant, nihilistic, and anarchistic forces which have

become entrenched, for the most part, on college campuses and which threaten the orderly process of education as the

forerunner of a more determined effort to destroy our economic, social, and political structures (pp.308).”

13 According to Mari Buitrago’s book Are You Now or Have You Ever Been in the FBI Files?, the FBI Manual of

Instruction define ‘extremist’ as those whose activities ‘aimed at overthrowing, destroying, or undermining the

Government of the United States…by illegal means or denying the rights of individuals under the Constitution.’ The

FBI included among ‘extremists’ the Black Panther Party, the Nation of Islam, the Ku Klux Klan, the American Indian

Movement—and Jerry Rubin.”

14 Wiener, Jon, Come Together, pp. xv: “Buried deep in the twenty-six pounds of files the Federal Bureau of

Investigation and the Immigration and Naturalization Service gathered on John Lennon, there is a report to FBI director

J. Edgar Hoover describing John's 1971 appearance in Ann Arbor, Michigan, at an antiwar rally. The FBI informers

who watched him knew what no one else in the audience did: John considered his appearance at the rally a trial run for

a national anti-Nixon tour, on which he would bring rock and roll together with radical politics in a dozen cities. He

had been talking about ending the tour in August 1972 at a giant protest rally and counterculture festival outside the

Republican national convention, where Richard Nixon would be re-nominated...Lennon prior to rally composed song

entitled, 'John Sinclair,' which song Lennon sang at the rally…John's appearance in Ann Arbor was his first concert in

the United States since the Beatles' 1966 tour. He shared the stage with the most prominent members of the "Chicago

Seven," who had led the antiwar protests outside the Democratic national convention in 1968: Jerry Rubin, founder of

the Yippies, Bobby Seale, chairman of the Black Panther Party; Dave Dellinger, the veteran pacifist; and Rennie Davis,

the New Left's best organizer. Stevie Wonder made a surprise appearance. All of them called for the release from

prison of John Sinclair, a Michigan activist. Sinclair had led the effort to make rock music the bridge between the

antiwar movement and the counterculture, and between black and white youth. He had already served two years of a

ten-year sentence for selling two joints of marijuana to an undercover agent.”

15 Wiener, Jon, Gimme Some Truth, pp.254

16 Ibid, pp.208

17 Ibid, pp. 220

18 Ibid, pp. 136

19 Goldman, Albert, Elvis, pp. 556-560. Nixon appointed Elvis as a special agent of the Bureau of Narcotics and

Dangerous Drugs (BNDD). Ironically, at this time, Elvis was heavily using the opiate Dilaudid, also known as

“drugstore heroin.”

20 Krogh, Egil “Bud,” The Day Elvis Met Nixon, pp. 35

21 Goldman, Lives of John Lennon, pp.439-40

22 Ibid, pp. 450

23 Brown, Peter, pp. 411

24 Photo from the “John Lennon Yoko Ono War is Over” website: http://www.strawberrywalrus.com/warisover.html

25 MacDonald, pp.223

26 Coleman, Ray, pp.408

27 Wiener, Gimme Some Truth, pp. 178

28 Ibid, pp. 220

29 Ryback, pp. 60: the Polish called the Beatles the “Bitels.”

30 From The Historical Political Development of Soviet Rock Music by Trey Donovan Drake, University of California,

Santa Cruz (http://www.powerhat.com/tusovka/titlepage.html): “Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin's main cultural official, was at

the head of the offensive against any Western influences ‘poisoning the consciousness of the masses.’ In 1947, his

bilious polemics were directed at a popular form of entertainment from the West; jazz. Zhdanov condemned the

“predilection for, and even a certain orientation toward modern, Western, bourgeois music, toward decadent music.”

31 Ibid, pp.40

32 From the article “Communism Destroyed” by Alexander Zheleznjak, published in “Kiev Post” (now “Kyiv Post”) in

1996

33 Ibid, pp. 9

34 Ibid, pp. 56

35 Dr. Pelyushonok has earned an interesting place in Beatles history as the co-creator and host of the first officially

authorized Soviet television special on the Beatles in 1991, titled “30 Minutes with the Beatles.” Because of the

Communist hardliner’s coup attempt that happened in Moscow in August of that year, the special was almost not aired.

But, thanks to Zheka, the show’s producer, who had made a copy of the program before reactionaries had a chance to

erase it, the program aired in December 1991.

36 Pelyushonok, pp.2

37 “You Say You Want a Revolution,” by Mikhail Safonov, History Today, August 2003.

38 Album cover photo from the Xavier Records website: http://x-rec.com/main/czech/egon_bondy.htm

39 From The Historical Political Development of Soviet Rock Music by Trey Donovan Drake, University of California,

Santa Cruz (http://www.powerhat.com/tusovka/titlepage.html)

40 BC News: FILM Friday, 23 March, 2001 - Beatles 'brought down communists'

(http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/film/1235862.stm

41 “You Say You Want a Revolution,” by Mikhail Safonov, History Today, August 2003.

42 “You Say You Want a Revolution,” by Mikhail Safonov, History Today, August 2003.

43 According to several sources, Havel was an ardent Frank Zappa and Lou Reed fan (both men visited him in

Czechoslovakia during his presidency); in Ryback’s document, Havel is also purported to be a big fan of John Lennon.

44 From an article on the Plastic People by Richard Vine, printed in The Guardian (London) on February 16, 2000,

titled “Rock Czechs;” subtitled “Rock bands may be famed for their lax attitude to authority but only one has ever

helped overthrow a government.”

45 From an article published in The Guardian (London) January 31, 2003 under the headline “The king of Bohemia:

This weekend Vaclav Havel steps down as Czech president,” by Timothy Garton Ash

46 From a July, 1990 article for the Los Angeles Times titled, “A Prague Spring for Rock 'n' Roll,” by Denise Hamilton

47 Havel, “Power to the Powerless,” pp.154-156

48 From an article published in The Guardian (London) January 31, 2003 under the headline “The King of Bohemia” by

Timothy Garton Ash: “...So much has changed in the two decades…his life, from dissident to president, his dress, from

jeans to dark suits, his health, from bad to worse, the whole world around, from communism to capitalism, Warsaw

pact to Nato - but this image remains, in my mind's eye, the constant, the irreducible Vaclav Havel...It was like this

when I first met him, sitting in the bay window of his old flat high above the river Vltava in Prague, thin and drawn

after nearly four years as a political prisoner of the communist regime. It was like this last time we talked, in a congress

centre that was built for Communist party conferences but now awaited a Nato summit. The subject of the wry

observation has changed, of course. Back then, in 1984, it was about the secret policeman who followed him

everywhere. When Havel went to a sauna, the secret policeman, middle-aged and portly, hurried up to him and said,

"Excuse me, Mr. Havel, but I have a heart pacemaker and it's not good for me to go in there. Would you mind waiting

while I call for someone else?" Now it was about his fellow presidents, George W Bush and Jacques Chirac, and

whether they would stay for the amazing after-dinner hymn to freedom, combining Beethoven's Ode to Joy, the

Marseillaise and John Lennon's ‘Power to the People,’ that he had specially commissioned for the Nato summit - and

for his own farewell.”

49 Ryback, pp.192

50 http://www.bagism.com/library/lennonwall.html

51 Ryback, pp. 197

52 http://www.bagism.com/library/lennonwall.html

53 From an article By Ondrej Hejma, published by the Associated Press January 28, 2003 under the headline “Pictures

from a Revolution: ‘The tanks are rolling out, the Stones are rolling in’”

54 http://www.mtv.com/news/articles/1449516/20011002/story.jhtml

55 John Lennon has an official Capital Records website (http://hollywoodandvine.com/johnlennon/) where visitors can

watch a streaming version of the video for “Working Class Hero,” join the Capital Records mailing list, or buy Lennon

records online.

56 In a July, 1990 article for the Los Angeles Times titled, “A Prague Spring for Rock 'n' Roll,” Denise Hamilton noted

that “...after a visit to Prague this year, writer Philip Roth noted that in a censorship culture where everybody lives a

double life, literature becomes a life preserver, the remnant of truth that people cling to. The same was true of

alternative rock 'n' roll. While many musicians in Eastern Europe never set out to write political lyrics, the system

forced them into it. Now, they find the lines between politics and culture blurring again.”

Bibliography

Ambrose, Stephen E., Nixon: The Triumph of a Politician 1962-1972. (New York: Simon

& Schuster, 1989)

The Beatles Anthology, by the Beatles, (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2000)

Peter Brown and Steven Gaines, The Love You Make: an Insider’s Story of the Beatles.

(New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983)

Buitrago, Ann Mari, Are You Now or Have You Ever Been in the FBI Files? (New York:

Grove Press, 1980)

Coleman, Ray, Lennon. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1984)

Dubcek, Alexander, Hope Dies Last: the Autobiography of Alexander Dubcek. Edited

and translated by Jiri Hochman. (New York: Kodansha International, 1993)

Goldman, Albert, The Lives of John Lennon. (New York: William Morrow and

Company, 1988)

Elvis. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981)

Gorbachev, Mikhail Sergeevich, Memoirs. (New York: Doubleday, 1996)

Mikhail Gorbachev and Zdenek Mlynár, Conversations with Gorbachev: on Perestroika,

the Prague Spring, and the Crossroads of Socialism. Translated by George Shriver with a

foreword by Archie Brown. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002)

Green, John, Dakota Days. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983)

Giuliano, Geoffrey, Lennon in America. (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2000)

Hampton, Wayne, Guerilla Minstrels: John Lennon, Joe Hill, Woody Guthrie, and Bob

Dillon. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1986)

Harry, Bill, The Book of Lennon. (New York: Delilah Books, 1984)

Havel, Vaclav, Disturbing the Peace. (New York: Vintage Books, 1990)

Open Letters: Selected Writings, 1965-1990. Selected and edited by Paul

Wilson. (New York: Knopf, 1991)

Hoover, J. Edgar, J. Edgar Hoover Speaks Concerning Communism. (Washington, D.C.:

Capital Hill Press, 1970)

Masters of Deceit: The Story of Communism in American and How to

Fight It. (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1958)

Krogh, Emil “Bud,” The Day Elvis Met Nixon. (Bellevue, WA: Pejama Press, 1994)

Imagine: John Lennon [video recording] / Warner Bros. Inc. (Burbank, CA: Warner

Home Video, 1988)

MacDonald, Ian, Revolution in the Head: the Beatles' Records and the Sixties. (New

York: H. Holt, 1994)

Mitchell, Greg, Tricky Dick and the Pink Lady: Richard Nixon vs. Helen Gahagan

Douglas—Sexual Politics and the Red Scare, 1950. (New York: Random House, 1998)

Morgan, Edward P., The 60s Experience: Hard Lessons about Modern America.

(Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991)

Pelyushonok, Dr. Yury, Strings for a Beatle Bass: The Beatles Generation in the USSR.

(Ottawa: Ply Publisher, 1999)

Powers, Richard Gid, Secrecy and Power: The Life of J. Edgar Hoover. (New York: The

Free Press, 1987)

Ramet, Sabrina Petra, Rocking the State: Rock Music and Politics in Eastern Europe and

Russia. (Boulder: Westview Press, 1994)

Riley, Tim, Tell Me Why: a Beatles Commentary. (New York: Knopf, 1988)

Ryback, Timothy, W., Rock Around the Bloc: a History of Rock Music in Eastern Europe

and the Soviet Union. (Oxford: Oxford university Press, 1990)

Safonov, Mikhail, “You Say You Want a Revolution,” History Today, August 2003

Elizabeth Thompson and David Gutman, The Lennon Companion: Twenty-five Years of

Comment. (New York: Schirmer Books, 1987)

Troitsky, Artemy, Back in the USSR: the True Story of Rock in Russia. (Boston: Faber

and Faber, 1988)

Irwin and Debi Unger, The Times Were a Changin’: the Sixties Reader. (New York:

Three Rivers Press, 1998)

Wiener, Jon, Come Together: John Lennon in His Time. (New York: Random House, 1984)

Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files. (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1999)

Yenne, Bill, The Beatles. (New York: Gallery Books, 1989)