|

|

|

"Flew in from Miami Beach BOAC

Didn't get to bed last night

On the way the paper bag was on my

knee

Man I had a dreadful flight

I'm back in the U.S.S.R.

You

don't know how lucky you are boy

Back in the U.S.S.R.

Been away so long I hardly knew the place

Gee it's good to be back

home

Leave it till tomorrow to unpack my case

Honey disconnect the

phone

I'm back in the U.S.S.R.

You don't know how lucky you are boy

Back in the U.S.

Back in the U.S.

Back in the U.S.S.R."

"Back in the U.S.S.R." excerpt of the lyrics composed and written by

John Lennon/Paul McCartney

Copyright by Northern Songs Ltd,

1968 |

INTRODUCTION:

On August 10, 2000, both Tony Copple and I received e-mail notices from ABC

Television in New York requesting contact information about Dr. Yury Pelyushonok

-- a local author whose literary work we feature here at the Ottawa Beatles Web

Site. The request came in from Alex Kay of ABC Television who alerted us in her

e-mail about their production of a Beatles special tentatively titled "How The

Beatles Changed the World" -- which later became known as "The Beatles

Revolution." We forwarded her the appropriate contact information and a as

result Dr. Pelyushonok found himself making an appearance in the show.

Shortly after Dr. Pelyushonok's interview with ABC television, we decided to

alert the Ottawa Citizen about the upcoming Beatle special as a potential story

for their paper. The Ottawa Citizen saw merit in our suggestion and so they

chose free-lance reporter Bruce Deachman to interview Dr. Pelyushonok in his

west-end home. The Ottawa Beatle Site wishes to express grateful acknowledgment

to Bruce Deachman and the Ottawa Citizen for granting us use of their

full-length paper edition report which appeared on Friday, November 17, 2000.

-- John Whelan, Chief Researcher for the Ottawa Beatles Site

He loves them, yeah, yeah, yeah

Ottawa writer looks at Beatles' influence on Soviet culture

Bruce Deachman

The Ottawa Citizen

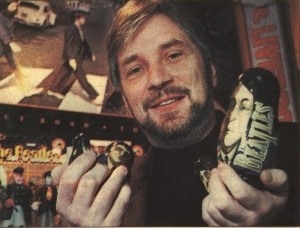

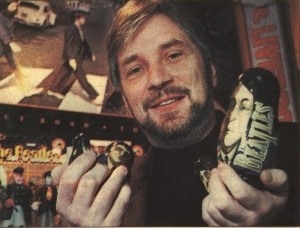

Photo by Rebecca Stevenson, the Ottawa Citizen. Yury

Pelyushonok, author and collector of Beatles

trinkets.

|

There's an unmistakable and pervasive theme to the basement office of

Yury Pelyushonok's west-end Ottawa home.

Pictures of the Beatles adorn the walls, alongside Soviet LP covers of the

Fab Four. The famous Abbey Road shot hangs above fiveYellow Submarine Beatles

toys, still in their original packaging. A few 45s are on the wall, too, as is a

39-cent Beatles hairbrush. Wooden Russian dolls, bearing likenesses of the

Liverpudlians, rest on the window-sill. There's a Beatles mug, plastic rings and

glow-in-the-dark Yellow Submarine stickers. A number of framed commemorative

postage stamps of the Beatles, from countries like Tanzania and St. Vincent, are

also on display, my favourite being the communist-mocking, two-stamp set issued

by Abkhazia, bearing the images of Groucho Marx and John Lennon.

"You're a bit of a fanatic," I say, stating the obvious.

"No, not really," Pelyushonok answers. "It's not like I listen to their music

250 times a day."

I wonder.

A tall 43-year old man, he bends over to press the 'Play' button on a

cassette-player. "Listen," he says, and the room is filled with the words and

music to The Yeah-Yeah Virus, a song that he and his translator-cum-fiance, Olga

Sansom, wrote, and which is being performed by a neighbour, John Jastremski.

"You may know of him," says Pelyushonok, telling me the name of the Ottawa

band that the singer was, or is, in. Unable to recognize the name, I shake my

head and listen to the song. It is reminiscent of old Paul Simon with a dash of

the Monkees thrown in.

"I was thinking of Can't Buy Me Love when I wrote it," he says.

While in the West the Beatles stepped on all the rules

The '60s beat

was echoing through all the Soviet schools.

Every Russian schoolboy wants to

be a star

Playing Beatles music, making a guitar.

Teachers looked upon

all this as if it were a sin,

We were building Communism but the Beatles

butted in.

'Nyet!' to Beatles music. 'Da!' the students said.

Even Comrade

Brezhnev sadly shook his head...

The song's lyrics pretty accurately sum up Pelyushonok's experiences growing

up in the '60s and '70s in the Soviet Union, where access to Western culture was

spare, and misinformation rampant.

"Being a Beatles fan in North America was easy," he says. "Not so in Russia.

In those days, he explains, it was illegal to bring a Beatles record into the

country and if you were found with one, it was usually confiscated. As a member

of the Soviet national fencing team, he witnessed the same airport routine time

and again: "If, say, a famous sportsman came back from a foreign country, the

customs authorities would ask, 'Do you have a Beatles' record?"

"And if you did, they would put the record on this special device, scratch

it, and then return it to you as a souvenir."

Recordings that did manage to pass through the tight screen were as good as

gold, he says. "Some diplomats, some famous, famous athletes, and some sailors

managed to smuggle in illicit records," he says. "Immediately, the whole country

would have copies of these on reel-to-reel tape."

Most of the Beatles music that Pelyushonok managed to listen to was, at best,

third- or fourth-generation copies.

"'Beatlyi' was the Russian word to describe things by the Beatles,"

Pelyushonok adds. "I remember hearing that word for the first time in 1964, when

I was in Grade 1. Even then, I knew exactly what it meant.

"I don't know how it got around. It wasn't in the newspaper, it wasn't

anywhere. But it's like corruption; you just sense it."

Pelyushonok has recently published a book chronicling his experiences,

titled, Strings For A Beatle Bass: The Beatles Generation in the USSR. The book

explains the Soviet opinion of the Beatles and the importance and prevalence of

the Fab Four in Russian cultural history.

According to Pelyushonok, it began as a small article, written when he

attended the 1995 Ottawa Beatles Convention at the National Museum of Science

and Technology. (He had emigrated to Canada in 1993, because of political

conditions in Russia. "I couldn't stay any longer.")

Pelyushonok, a doctor in the Soviet Union whose training isn't recognized as

a doctor in Canada, got a job at Wal-Mart. At night, he began writing down his

stories of growing up and the connection to the Beatles.

"The youth of the Soviet Union do not need this cacophonous rubbish," stated

Soviet leader Nikita Krushchev of the Beatles in the early 1960s. "It's just a

small step from saxophones to switchblades."

Yet the Soviet youth, claims Pelyushonok, did need the Beatles, and went to

enormous lengths to be more like them. Pelyushonok contends that the Beatles,

and not other bands of the time, were the single-most major factor in shaping

pop culture behind the Iron Curtain.

"They were considered the big capitalist threat during the Cold War," he

says.

"You could bring Rolling Stones albums into the country, later on, but not

the Beatles.

"You know why? I think it's because the Beatles were an event. The Rolling

Stones were a rock band, but the Beatles were the cultural event of our century.

"One-hundred out of 100 kids, if asked who invented the electrical guitar,"

he continues, "would answer 'The Beatles.' Who invented rock-and-roll? The

Beatles.

"Every event has a master, and the master of modern music was the Beatles."

In his book, Pelyushonok describes the lengths that he and others went to in

order to build a guitar. For example, since only traditional seven-string

acoustic folk guitars were readily available then, and bass guitars were unheard

of, he built his own bass guitar, only to discover that bass strings were

impossible to get. The solution was to steal some from a school piano, an act

that didn't go unnoticed at the next school assembly, nor one that went

unpunished. At the New Year's Eve concert that his newly-formed "beat-band"

played at, retribution was final, as the piano strings snapped his guitar in

half.

It seemed everyone was in a band then, says Pelyushonok, and they all played

Beatles' songs, whether they knew the words or not. Curiously, however, they

never performed Beatles' songs in public.

In the U.S.S.R., the Beatles were surrounded by such an aura of legend and

fame," he writes in his book, "that no one dared to even approach them. The word

Beatles was almost sacred, just like the cow in India. To go out onto the stage

and imitate John Lennon would have been...like a faithful Catholic dressing up

as Jesus Christ for Halloween."

Rolling through the '60s, '70s, '80s and '90s, the book includes the death of

John Lennon, by which time the Soviet propaganda machine has turned 180 degrees,

contending that the American secret service had assassinated Lennon, a proponent

of peace and a friend of the Soviet Union's.

Recently, the book came to the attention of executives at ABC, whose Beatles

documentary, The Beatles Revolution, airs tonight at 8:00 p.m.

Pelyushonok was flown to New York last month, where he was interviewed for

hours for the show.

"It was us, listening to the Beatles," he says, "that became Russia's lost

generation.

"And we grew up and became the deputies, and we became the officers, and

that's what changed the country.

"The Beatles brought this message about love and peace," he adds, "but there

was this thundering silence and fury. (The authorities) wouldn't listen. They

wouldn't pay attention. "But you know what the Beatles did? They allowed us a

little bit of a way to escape when there was no escape."

Pelyushonok bends over once more to play the tape. The lyrics again tell his

story:

Each Comrade's child was in a band,

The yeah-yeah virus swept the

land,

What could they do? What could they say?

A generation gone astray.

The yeah-yeah had them in its sway.

What could they do, what could they

say? They walked away..."

Copyright by the Ottawa Citizen, November 17, 2000.

Used with

permission.

Flag of Russia courtesy of Multimedia Palace

Ottawa Beatles

Site