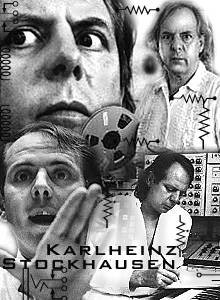

The man who fell to earth

EARLY summer, 1960: a young German composer is putting the finishing

touches to a piece of music titled Kontakte. One thousand hours of studio time

have been condensed into a short, 34-minute work for piano, percussion and

something called “electronic sounds”. It premieres at Cologne Radio’s concert

hall on June 11, and is later released as a record. One day, Kontakte will be

deemed a masterpiece.

EARLY summer, 1960: a young German composer is putting the finishing

touches to a piece of music titled Kontakte. One thousand hours of studio time

have been condensed into a short, 34-minute work for piano, percussion and

something called “electronic sounds”. It premieres at Cologne Radio’s concert

hall on June 11, and is later released as a record. One day, Kontakte will be

deemed a masterpiece.

Around the same time in Hamburg, a German photographer is taking pictures

of her musician boyfriend, Stuart Sutcliffe, and his bandmates John Lennon,

George Harrison and Paul McCartney. Those pictures will one day be famous.

There’s no way of knowing whether The Beatles ever tuned in to German radio

and heard Kontakte, but it would be pleasing to think that’s how they first

heard the name Karlheinz Stockhausen and that, even as they set about shaping

the sound that would revolutionise the 1960s, they had already absorbed some

of the radicalism and spirit of his intense, difficult music.

Today, the whole planet knows about the Fab Four, while Stockhausen has to

be content with his billing as the world’s most famous living composer. He has

been cited as an influence by everyone from Miles Davis to Björk, via Frank

Zappa and Brian Eno, and innumerable books have been written about his

pioneering electronic music. He has also been described variously as a

monster, a genius and – by the British philosopher and musicologist Roger

Scruton – a pseudo-intellectual hippy- mystic with a “liberating gift” for

creating “utter nonsense”. His name alone has become shorthand for the most

outrageous excesses of the avant garde.

Now 76, Stockhausen still lives near Cologne, in a house with hexagonal

rooms in the middle of a forest about 45 minutes from the city. He designed

the house himself to look like one of his musical scores. But we meet instead

at his studio complex in the nearby hamlet of Kürten. Fitting the hippy-mystic

tag, my visit has already taken on the air of a pilgrimage: an e-mail from his

assistant, Suzanne, telling me how to get to Kürten ends with the words:

“Stockhausen will come at precisely 15.30.”

The directions are hardly necessary. I turn a corner on the twisting,

narrow road and there, at the start of the village, is a long whitewashed

building. Peering through the windows, it’s obvious this isn’t a scout hut: I

can see two enormous gongs and, hanging from one of the neat rows of shelves

which contain copies of Stockhausen’s bizarre scores, a strange looking stage

costume.

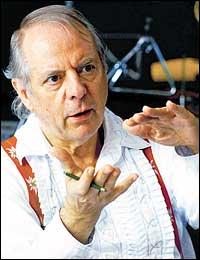

As promised, the man himself arrives punctually, chaperoned by Suzanne and

by his companion, Kathinka. They’re both musicians when not helping run the

Stockhausen empire, and Suzanne will record the interview for the archive

while Kathinka takes pictures and translates when the maestro needs help. It

doesn’t happen often; Stockhausen’s English is near flawless.

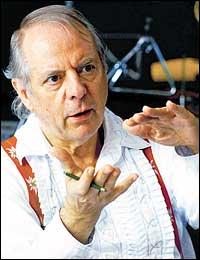

All three are wearing white trousers, but Stockhausen tops his with a

bright orange jumper. His famous flowing locks are shorter now but his hair

still curls over his collar. The eyes, often described as blue, look more

grey-green in the late afternoon sunlight. He is big and he has huge hands. He

worked as a farm labourer, I recall, before he began his experiments with

sound. His handshake is tight and strong.

We’re to conduct the interview in the studio, but first I’m asked to put a

pair of huge felt slippers on over my shoes. They cut down on noise but they

make movement difficult, so I ski rather than walk into the room. Stockhausen,

to whom the slipper rule obviously doesn’t apply, wears a pair of white

Birkenstock sandals. Like his hands, his feet are huge. Although courteous and

personable, he cuts an eccentric figure.

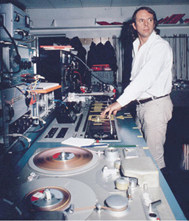

The studio itself feels like something out of 2001: A Space Odyssey. A

massive whitewashed space, it has windows down two sides and a mixing desk in

the middle. The only other objects are a grand piano, several sleek pine music

stands, eight huge speakers arranged at regular intervals and a massive

painting depicting a Stockhausen score. He has long since jettisoned

conventional musical notation, preferring instead a system of graphs, numbers,

arrows and symbols. It’s one of the reasons he likes to use the same musicians

when he records – newcomers would have too much difficulty understanding his

scores.

Stockhausen has recently finished Licht (Light), an epic opera cycle based

on the seven days of the week. He started it in 1977 and the last and seventh

part premiered at the Donaueschingen Music Festival in October 2004. Were it

to be performed as a whole, it would run to over 30 hours. It is for such

grand gestures that he is mocked and venerated in equal measure.

Nevertheless, there are plans to mount the whole thing in 2008, the year of

Stockhausen’s 80th birthday. “I have planned since the very beginning [for it

to be performed all together] but the world does not do what I want it to,” he

says. “Maybe I can still experience a performance of Licht, the complete

cycle. It is an enormous project.”

Undeterred, he has already started on another vast project. It’s called

Klang (Sound), a cycle of works based on the 24 hours of the day. The first

part is already finished and will premiere in Milan Cathedral on May 5. As

part of his research for the other 23 pieces, Stockhausen says he is studying

the different qualities possessed by the various hours of the day, as if

savouring their tastes before capturing them in sound. It seems a

breathtakingly audacious undertaking for someone of his age but he seems to

need these huge tests. You get the sense of a man actually trying to peer into

time itself.

“To compose a large project of music is fascinating because I am divining,

as I have in all my works since the beginning, larger organisms from

nucleuses,” he explains. “Each work is one nucleus, then I develop the

nucleus, make it grow in all aspects.”

That beginning came in 1951 with Kreuzspiel (Crossplay), a piece for oboe,

clarinet, piano and percussion which Stockhausen later described as “an

intersection of temporal and spatial phenomena”. He was 23 at the time of its

first performance, and a music student in Cologne.

The composer was born in 1928 in Mödrath, a village near Cologne. His

father, Simon, was a schoolteacher who was later killed in the second world

war. His mother, Gertrud, suffered from depression and was institutionalised

in 1933. She was put to death in 1941, a victim of the Nazi euthanasia policy.

Stockhausen showed a precocious musical talent from an early age. By the

time he was six he could hear a tune on the radio and play it back immediately

on the piano. By eight, he was earning pocket money playing folk tunes in

restaurants.

Stockhausen showed a precocious musical talent from an early age. By the

time he was six he could hear a tune on the radio and play it back immediately

on the piano. By eight, he was earning pocket money playing folk tunes in

restaurants.

In 1952 he went to Paris to study with the composer Olivier Messiaen, the

champion of Musique Concrète – a new type of music using recorded sound as a

cornerstone of composition. By this time Stockhausen was married to his first

wife, Doris Andreae.

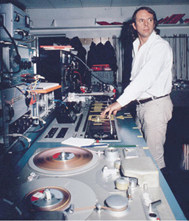

In 1953 Stockhausen returned to Germany where he began his longstanding

association with the radio station WDR. In the broadcaster’s electronic music

studio he started work on pieces such as Gesang Der Jünglinge (Song Of The

Youth), cutting, splicing and looping tape to produce his strange

constellations of sound. In the same year he began teaching at a musical

summer camp, the Darmstadt School. Famous or notorious, depending on your

point of view, it produced some of the coldest, most cerebral and brilliant

modern music of the late 20th century.

By the mid-1960s his works regularly premiered in Europe, India, Japan and

America. In 1966 he became a visiting professor at the University of

California and then travelled through Sri Lanka and Cambodia to Japan, where

he worked for a while. In the 1970s, now married to second wife Mary Bauermeister, he lived in France, Milan and London and worked in Japan, where

he began to write Licht in 1977.

Audiences in Glasgow and Edinburgh will have a chance to put this sprawling

career into perspective next month when Stockhausen undertakes his first ever

Scottish concerts, as part of the Triptych music festival. Fittingly, Kontakte

is one of the pieces to be performed, though in an earlier version which

consists solely of electronic sounds. He will also perform more recent works,

including Octophonie, from Licht.

Stockhausen asks me about the venues for his Scottish dates, curious about

their size and acoustic qualities. He needs to position eight sets of speakers

in the spaces, he says, “so that the sounds are moving vertically and

diagonally through the hall in many different spirals”. He prefers a room

which is square and which has “dry” sounds. Echoes bother him. I describe the

Tramway and the Queen’s Hall as a warehouse and a church. He nods, chewing

over the information.

I ask him what the audience will see while they listen. “Nothing,” he says.

“I will switch off the lights and project a very small moon so that people who

do not like to be in the complete dark have something to look at.”

One thing Stockhausen himself likes to look at is space. His answers to my

questions are peppered with references to his work as “space music” and “star

music” and he has a long and abiding interest in astronomy.

“I have a dear friend in America who is a librarian and he sends me the

astronomic magazines so I am informed of the latest discoveries in the

universe. There are some very extraordinary photographs.”

He had a telescope, he says, but he gave it to one of his six children. “It

was too small. Just looking at one of these fantastic photos of the galaxy,

you see much more.”

Astrology is another passion. His work Tierkreis is subtitled 12 Melodies

Of The Star Signs and in composing it he immersed himself in The Urantia Book.

Published in Chicago in 1955, it took the basic tenets of Christianity and

recast them as a belief system in which the Earth was a dog star called

Urantia and the universe was ruled over by a being called Michael.

Stockhausen took all this cosmological mysticism to heart. By 1980, after

he had started work on Licht, he was claiming that a “crazy dream” had told

him he was in fact from the star Sirius. Indeed Licht is essentially a

reworking of the Urantia story. In Licht, Michael is pitted against his arch

enemy Lucifer, the bringer of destruction, while Eve looks on. It involves

three singers, dancers, stage sets and costumes.

It was a typically convoluted explanation of all this that landed

Stockhausen in trouble after the September 11 attacks in the US. Asked by a

German journalist for a comment, Stockhausen appeared to describe the

destruction of the World Trade Centre as Lucifer’s greatest work of art. A

concert scheduled for Hamburg had to be cancelled amid the resulting media

storm, though a performance at London’s Barbican went ahead. Stockhausen

claimed he had been misquoted but issued an apology anyway. I ask him if he

was angered or hurt by the controversy and he embarks on another lengthy

explanation which again invokes Lucifer and Michael and which, if I’m honest,

I find a little hard to follow.

As with his words, so it is with his work. I

ask him if he thinks his music is misunderstood. “Yes,” he says. “Most of the

people think my music ought to entertain.” It doesn’t, evidently, but neither

does he want it viewed purely as an intellectual exercise. Instead he just

wants us to understand it, though he isn’t going to make that too easy.

“The people who want to understand the work I do have to spend at least as

much time as I have listening to it,” he says. In the case of his most recent

piece, that means listening for 55 days, seven hours a day. And if you can’t

spare the time – who can? – he has this advice: “Take just a bit. Better to

choose one or two works and concentrate … It’s better to go deep than broad.”

While Stockhausen may be lauded by modern DJs and dance musicians like The

Aphex Twin, serious classical music critics are divided over his continuing

importance. His mission to discover new laws of sound was realised in the

1950s and 1960s but since then he seems to have been journeying further and

further into the stratosphere, determined never to repeat himself or succumb

to cliché.

“Every musician has his clichés – in his muscles, in his body – when he

touches an instrument or when he sings,” he tells me. “I am very careful when

I compose not to allow any foreign property in.”

“Every musician has his clichés – in his muscles, in his body – when he

touches an instrument or when he sings,” he tells me. “I am very careful when

I compose not to allow any foreign property in.”

It’s an admirable sentiment but it makes his legacy hard to quantify. As

for the young DJs who sample or remix his work, he treats their efforts with a

mixture of bemusement and contempt. “On the whole planet, stealing has become

absolutely acceptable. People steal all the time – ideas, physical objects –

and reshape it and sell it.”

So what can he do? “I’m not a policeman and I am not a politician,” he

says. “But naturally I have my own inner ethic and morals.”

He tells me about a French organisation called Le Disque Du Centre De La

Bombe which commissioned an album of Stockhausen compositions remixed by six

contemporary composers. He calls it “garbage”.

There have been many others which have come to his attention. “An American

producer who produces what he calls ‘Plunderphonics’ wrote to me, saying that

he had made quite a lot of money by mixing my music with pop music of all

kinds and making new CDs. I didn’t really know how to react. I didn’t want to

hurt him.”

Stockhausen did write back, though. He told the Plunderphonic king it was

better to make something new. Other CDs he is sent just make him laugh. One

came from a young Hamburg band who had written a song about him and Bill Gates

getting stuck in a lift together. “That’s what they sing,” he chortles. “They

sing about a fight with Bill Gates in an elevator. It was very funny.”

Stockhausen has never met Bill Gates and nor, despite repeated attempts,

did he ever meet The Beatles. They were all joined in cardboard, however, on

the cover of the Sgt Pepper album. Stockhausen is sandwiched between Lenny

Bruce and WC Fields, his vacant stare suggesting he might have a hand on Mae

West’s backside.

“Oh yes, I think they had the discs,” he says when I mention the Sgt Pepper

homage and The Beatles’ citing of him as an influence. “I would have liked to

have met them. I was invited to by their manager. I had a few phone calls with

him. We wanted to do joint concerts in London, but then they went to the

States. Then John Lennon was shot. So it didn’t happen.”

However or whenever The Beatles discovered Stockhausen, there’s no doubting

the influence his music had on them. Paul McCartney has talked about his

admiration for the 1955 piece Gesang Der Jünglinge and John Lennon openly

admitted that 1967’s Hymnen (Anthems) was the inspiration for Revolution No 9,

from The Beatles’ White Album.

Today, of course, Paul McCartney sings The Frog Chorus and gets booked as

the half-time entertainment in the Super Bowl. Stockhausen, 15 years his

senior, appears alongside The Fall at leftfield Scottish rock festivals and

continues to scrape away at our understanding of sound. So it seems

appropriate, in a way, that he should have outlived Sutcliffe, Lennon and

Harrison. The modernity of The Beatles faded, but you sense that Stockhausen’s

never will.

I ask him if he thinks about death. Every day, he says. What does he think

is beyond it? He laughs. “I will see. But this morning I saw, for the first

time since last year, about 200 crocuses opening up. I said to Kathinka, who

was standing next to me: ‘This is how it will be when I die.’”

Life is a cosmic adventure, he says. “This life is like being imprisoned in

a body, in a house, in a country. But then after this life, I expect to see a

much broader view. A whole new scale of things.”

I leave him talking about his grandchildren – 16 or 17, he can’t remember –

and how they like to listen to his music. Doesn’t it scare them? I joke. “Ach,

children like to be scared,” he laughs. Then he tells me about his dentist,

who recently had twin boys. They wouldn’t sleep so Stockhausen asked for their

star sign and delivered a copy of Tierkreis (Zodiac).

“I said, ‘Make a loop out of Aquarius – because the boys were born on

January 22 this year – and play it over and over again and you will see, they

will fall asleep right away’. And it works!” He beams at me, pleased with

himself.

He also tells me that he’s looking forward to the two days off between his

Scottish concerts. He wants to see something of Glasgow and Edinburgh, these

cities he has heard of but never visited. Perhaps he’ll just go for a walk.

Keep an eye out, then, for a man in an orange jumper and white jeans, head

cocked to listen to a new sound. Or maybe just looking at crocuses as they

break open in the sun.

Stockhausen plays Glasgow’s Tramway on April 27 and the Queen’s Hall,

Edinburgh, on April 30 as part of the Triptych festival. Tickets: 0870 220

1116

27 March 2005

This article first appeared in the Sunday Herald

Online.

EARLY summer, 1960: a young German composer is putting the finishing

touches to a piece of music titled Kontakte. One thousand hours of studio time

have been condensed into a short, 34-minute work for piano, percussion and

something called “electronic sounds”. It premieres at Cologne Radio’s concert

hall on June 11, and is later released as a record. One day, Kontakte will be

deemed a masterpiece.

EARLY summer, 1960: a young German composer is putting the finishing

touches to a piece of music titled Kontakte. One thousand hours of studio time

have been condensed into a short, 34-minute work for piano, percussion and

something called “electronic sounds”. It premieres at Cologne Radio’s concert

hall on June 11, and is later released as a record. One day, Kontakte will be

deemed a masterpiece.

Stockhausen showed a precocious musical talent from an early age. By the

time he was six he could hear a tune on the radio and play it back immediately

on the piano. By eight, he was earning pocket money playing folk tunes in

restaurants.

Stockhausen showed a precocious musical talent from an early age. By the

time he was six he could hear a tune on the radio and play it back immediately

on the piano. By eight, he was earning pocket money playing folk tunes in

restaurants.  “Every musician has his clichés – in his muscles, in his body – when he

touches an instrument or when he sings,” he tells me. “I am very careful when

I compose not to allow any foreign property in.”

“Every musician has his clichés – in his muscles, in his body – when he

touches an instrument or when he sings,” he tells me. “I am very careful when

I compose not to allow any foreign property in.”