The Beatles Started a Cultural

Revolution

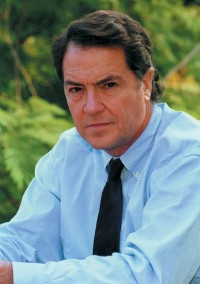

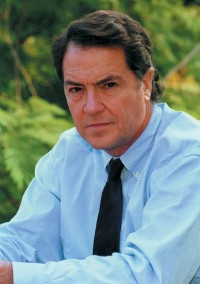

by John W. Whitehead

10/31/2005

It seemed to me a definite line was

being drawn. This was something that never happened before.—Bob

Dylan

To celebrate its 100th anniversary, Variety, considered the premiere

entertainment magazine, recently picked the top 100 entertainment icons of

the century. These are the men and women who have had the greatest impact on

the world of entertainment in the last 100 years.

On the list are film actors, directors, screenwriters, musicians, television

performers, animals, comedians, even cartoon characters. Named the top

entertainers were the Beatles—over such icons as Elvis, Humphrey Bogart, Bob

Dylan, Alfred Hitchcock and Rogers and Hammerstein, among others. According

to the article, the Beatles sit at the top because they transformed pop

music.

However, their impact was much greater than that. In fact, John, Paul,

George and Ringo unknowingly set in motion forces that made an entire era

what it was and, by extension, what it is today. The Beatles “presided over

an epochal shift comparable in scale to that bridging Classical Antiquity

and the Middle Ages,” writes professor Henry Sullivan, “or the transition

from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance.” Indeed, they played a central role

in catalyzing a transition from the Modern to the post-Modern Age.

Beatlemania hit the United States with full force in 1964. When the nation

tuned in to the Ed Sullivan Show, some 70 million Americans got their first

glimpse of the Beatles—the streets emptied and crime stopped.

It was February 9, and four English lads were singing to an

assassination-wearied country. That night, along with the Beatles, the

guests on the popular Sullivan show included Georgia Brown singing a

Broadway tune, several comedians, an Olympic athlete and an acrobatic act.

Amid this series of well-worn, non-controversial vaudeville acts came the

Beatles. With their mop-top haircuts and original music, they seemed like

visitors from another planet. Obviously, a cultural revolution was at hand.

There are several important ways the Beatles altered western history. First,

perhaps unintentionally, the Beatles helped feminize the culture. Presley

may have been revolutionary, but there was no gender revolution until the

Beatles came along. With the prominence they accorded women in their songs

and lives and the way they spoke to millions of young teenage girls about

new possibilities, the Beatles tapped into something much larger than

themselves. It eventually led to the empowerment of young women.

The implications of the Beatles’ relatively androgynous appearance had a far

more profound effect on sexual and women’s liberation than anyone could have

guessed at the time. “The Beatles set the tone for feminism,” according to

professor Elaine Tyler May.

Moreover, as Steven Stark points out in his insightful book on the group,

Meet The Beatles, the Beatles also “challenged the definition that

existed during their time of what it meant to be a man.” This ultimately

allowed them to help change the way men feel and look. The Beatles, as Dr.

Joyce Brothers recognized at the time, “display a few mannerisms which

almost seem a shade on the feminine side, such as tossing of their long

manes of hair. Very young ‘women’ are still a little frightened of the idea

of sex. Therefore they feel safer worshipping idols who don’t seem too

masculine, or too much the ‘he-man’.” To this effeminacy should be added the

early Beatles’ preference for high falsetto leaps in their vocals.

Second, the Beatles converged with their era—the sixties generation—in an

almost unprecedented way. At no other time in history, or since, has a

generation been so connected. The vehicle was rock music. And the Beatles

helped create an aural culture.

American demographics also played a major role in what was happening with

the emerging generation. The baby boom began in 1946 and lasted until 1964,

producing 78 million children. In the first years of American Beatlemania,

these boomers were aged from 18 on down to a couple of days old. This

represented a tremendous concentration of the population—over a third of the

nation’s total—in the teen and sub-teen bracket. This was a vast army of

potential Beatle fans hooked on music.

This fascination with music brought the sixties generation into a collective

whole. “Perhaps the most important aspect of the Beatles’ attraction,”

writes Stark, “during that influential era was their collective synergy.” In

other words, the Beatles popularized the sanctity of “the group.” With the

Beatles, the whole, thus, was always greater than the sum of the parts. This

gave them a dazzling appeal to millions who worshipped them.

Third, the religious allure of the Beatles was a vital factor in allowing

the group to endure. John Lennon was onto something in 1966 when he compared

the group’s popularity with that of Jesus Christ. Multitudes flocked to them

and even brought sick children to see if the Beatles could somehow heal

them. Thus, those who have seen elements of religious ecstasy in Beatlemania

are not wrong.

Religion, it must not be forgotten, has its roots in spiritual bonding. And

the Beatles had a powerful appeal to a generation in calling forth a

spiritual bonding. It was so intoxicating that it created mass hysteria. In

this way, the Beatles—especially with their elevation to a kind of

sainthood—have become modern counterparts to the religious figures of the

past.

As such, the Beatles, as new spiritual leaders, came to embody the values of

the counterculture in its challenge to “the Establishment.” They celebrated

an alternative worldview. It was a vision of a new possibility. And they

sang and lived this vision for others.

Finally, the Beatles had a worldwide power over millions of people that was

singular in history among artists. In 1967, with the release of their

Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band album, as one critic noted, it was

the closest Europe had been to unification since the Congress of Vienna in

1815. Most thought North America could have been included as well. And the

Beatles became the embodiment of the Summer of Love with their live global

BBC television broadcast of “All You Need Is Love” in June 1967.

Approximately 400 million people across five continents tuned in.

This type of power was something new. Before, only popes, kings and perhaps

a few intellectuals could hope to wield such influence in their lifetimes:

“Only Hitler ever duplicated their power over crowds,” said Sid Bernstein,

the promoter who set up some of their first concerts in America.

The Beatles had the good fortune to emerge at a unique time when musicians

could become forces for social change. It was a time when music was the most

vital force in young people’s lives—something that will never happen again

and something that was never intended by the Beatles themselves. As George

Harrison said: “We were four relatively sane people in the middle of

madness.”

Constitutional attorney and author John W. Whitehead is founder and

president of The Rutherford Institute. He can be contacted at

johnw@rutherford.org.

Information about the Institute is available at

www.rutherford.org.

Copyright © by John W. Whitehead and The

Rutherford Institute, 2005. Ottawa Beatles publication, November 2, 2005.

Used with permission with our sincere thanks!

|