Pure Freedom Versus Commitment - The changing values of the Counter Culture - By James DeWilde

Published by The Paper, Volume 3, Number 2, September 14, 1970, as a student weekly newspaper for the Loyola College and Sir George Williams University of Montreal.

Both the college and university merged on August 24, 1974 and created Concordia University.

The article was researched by John Whelan for the Ottawa Beatles Site.

Clean keyboard format has been transcribed underneath the report.

|

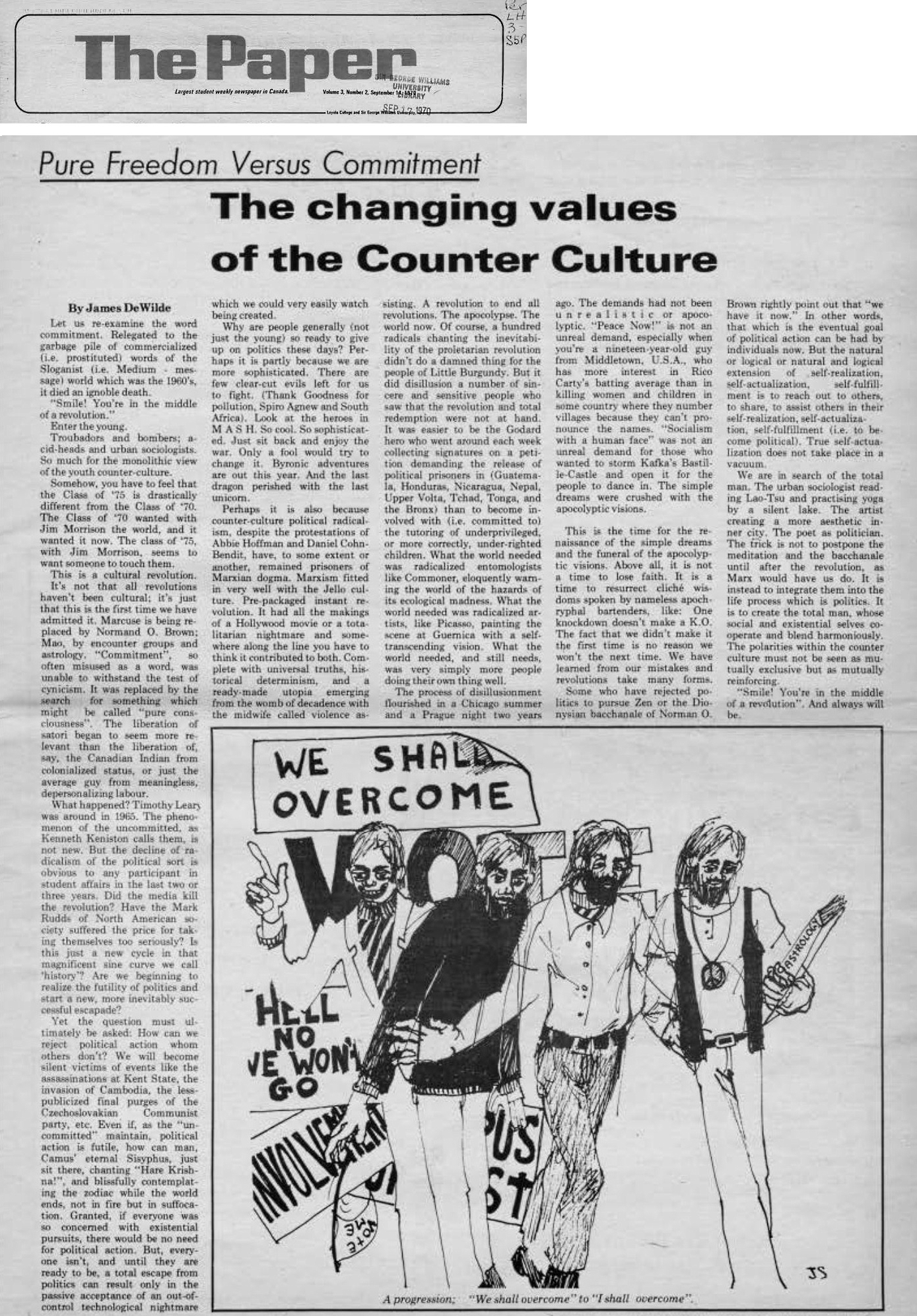

Pure Freedom Versus Commitment - The changing values of the Counter Culture - By James DeWilde Published by The Paper, Volume 3, Number 2, September 14, 1970, as a student weekly newspaper for the Loyola College and Sir George Williams University of Montreal. Let us re-examine the word commitment. Relegated to the garbage pile of commercialized (i.e. prostituted) words of the Sloganist (i.e. Medium - message) world which was the 1960's, it died an ignoble death. "Smile! You're in the middle of a revolution." Enter the young. Troubadors and bombers; acid-heads and urban sociologists. So much for the monolithic view of the youth counter-culture. Somehow, you have to feel that the class of '75 is drastically different from the class of '70. The Class of '70 wanted with Jim Morrison the world, and it wanted it now. The Class of '75, with Jim Morrison, seems to want someone to touch them. This is a cultural revolution. It's not that all revolutions haven't been

cultural; it's just that this is the first time that we have admitted

it. Marcuse is being replaced by

Norman O. Brown;

Mao, by encounter

groups and astrology, "Commitment", so often misused as a word, was

unable to withstand the test of cynicism. It was replaced by the search

for something which might be called "pure consciousness". The

liberation of satori

began to seem more relevant than the liberation of,

say, the Canadian Indian from colonized status, or just the average guy

from meaningless depersonalizing labour. Why are people generally (not just the young) so ready to give up on politics these days? Perhaps it is partly because we are more sophisticated. There are few clear-cut evils left for us to fight. (Thank Goodness for pollution and Spiro Agnew and South Africa). Look at the heroes in MASH. So cool. So sophisticated. Just sit back and enjoy the war. Only a fool would try to change it. Byronic adventures are out this year. And the last dragon perished with the last unicorn. Perhaps it is also because counter-culture political radicalism, despite the protestations of Abbie Hoffman and Daniel Cohn-Bendit, have, to some extent or another, remained prisoners of Marxian dogma. Marxism fitted in very well with the Jello culture. Pre-packaged instant revolution. It had all the makings of a Hollywood movie or a totalitarian nightmare and somewhere along the line you have to think it contributed to both. Complete with universal truths, historical determinism, and a ready-made utopia emerging from the womb of decadence with the mid-wife called violence assisting. A revolution to end all revolutions. The apocolypse. The world now. Of course, a hundred radicals chanting the inevitability of the proletarian revolution didn't do a damned thing for the people of Little Burgundy. But it did disillusion a number of sincere and sensitive people who saw that the revolution and total redemption were not at hand. It was easier to be the Godard hero who went around each week collecting signatures on a petition demanding the release of political prisoners in (Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Nepal, Upper Volta, Tchad, Tonga, and the Bronx) than to become involved with (i.e. committed to) the tutoring of the underprivileged, or more correctly, under-righted children. What the world needed was radicalized entomologists like Commoner, eloquently warning the world of the hazards of its ecological madness. What the world needed was radicalized artists, like Picasso, painting the scene at Guernica with a self-transcending vision. What the world needed, and still needs, was very simply more people doing their own thing well. The process of disillusionment flourished in a Chicago summer and a Prague night two years ago. The demands had not been unrealistic or apocolyptic. "Peace Now!" is not an unreal demand, especially when you're a nineteen-year-old guy from Middletown, U.S.A., who has more interest Rico Carty's batting average than in killing women and children in some country where they number villages because they can't pronounce the names. "Socialism with a human face" was not an unreal demand for those who wanted to storm Kafka's Bastilie-Castle and open it for the people to dance in. The simple dreams were crushed with the apocolyptic visions. This is the time for the renaissance of the simple dreams and the funeral of the apocolyptic visions. Above all, it is not time to lose faith. It is time to resurrect cliché wisdoms spoken by nameless apochryphal bartenders, like: One knockdown doesn't make a K.O. The fact that we didn't make it the first time is no reason we won't the next time. We have learned from our mistakes and revolutions take many forms. Some who have rejected politics to persue Zen or the Dionysian bacchanale of Norman O. Brown rightly point out that "we have it now." In other words, that which is the eventual goal of political action can be had by individuals now. But the natural or logical or natural and logical extension of self-realization, self-actualization, self-fulfillment is to reach out to others, to share, to assist others in their self-realization, self-actualization, self-fulfillment (i.e. to become political). True self-actualization does not take place in vacuum. We are in search of the total man. The urban sociologist reading Lao-Tsu and practising yoga by a silent lake. The artist creating a more aesthetic inner city. The poet as politician. The trick is not to postpone the meditation and the bacchanale until after the revolution, as Marx would have us do. It is instead to integrate them into the life process which is politics. It is to create the total man, whose total and existential selves cooperate and blend harmoniously. The polarities within the counter culture must not be seen as mutually exclusive but as mutually reinforcing. "Smile! You're in the middle of a revolution". And always will be. The above article was e-published on August 27, 2020 Related link from the National Film Board of Canada: "Little Burgundy" When an old area of a city is to be demolished to make way for a new low-rental housing development, is there anything that the residents can do to protect their own interests? This film, produced in 1968, airs such a situation in the Little Burgundy district of Montréal. It shows how citizens organized themselves into a committee that made effective representations to City Hall and influenced the housing policy. Little Burgundy, Bonnie Sherr Klein & Maurice Bulbulian, provided by the National Film Board of Canada This page was updated with the inclusion of the NFB video on December 3, 2020 |