|

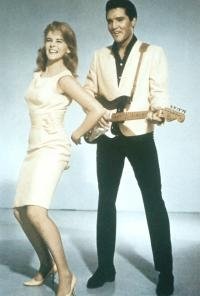

Photo credit: © Maclean's magazine, 1964 How Elvis survived the faddish years, and why the Beatles may go on forever by Wendy Michener for Maclean's magazine, Sept 19, 1964 edition. THE LAST TIME the Beatles visited America, some knowing teenagers greeted them with a sign saying: "Elvis is Dead. Long live the Beatles." That just about sums up the situation, even though Elvis is still very much with us. The latest Elvis movie (his fifteenth), Viva Las Vegas, is on the way to making a profit just like all the others. But Presley is no longer the sort of star that adolescent girls lose their cool over. Now nearing thirty, Presley has become the most decorous of sex symbols, a well-groomed, reliable, right-thinking entertainer who endears himself to his elders by calling them "sir" or "ma'am." The offending sideburns and gyrations have gone the way of all fads, and The Pelvis has become a clean-cut commercial personality like Annette Funicello, Frankie Avalon, and all the rest of the beach-party swimming-surfing crowd. His movies no longer revolve around an adolescent hero in conflict with the square older generation -- there's not a nasty daddy or a horrid mummy anywhere in Viva Las Vegas -- but around racing cars, gambling casinos and other playboy pursuits, like Ann-Margret. Presley has abandoned his teenage fans, not vice-versa, for the greater security of a family audience.

The people who thought Presley would quickly swivel his way into obscurity, and who are now predicting a fast fade-out for the Beatles, reckon without the star-making quality of the movies. If, as Marshall McLuhan says, the medium is the message, then the message of the movies is stardom, the sainthood of personality. Presley has endured not as a teen idol, but as a singing movie star; and the Beatles are well on their way to making the same transition with their first movie, A Hard Day's Night. In most movies that are produced to capitalize on teenage fads, the plot usually concerns a group of photogenic adolescents who are trying to arrange a twist party, a hootenanny, or some other event that provides an excuse for slinging together a bunch of musical numbers. In the end, they succeed despite adult interference, and the camera thereafter concentrates on all the shapely young bottoms in motion. But A Hard Day's Night, surprise, surprise, is a joyful departure from this well-worn formula. It can hardly be what beatlemaniacs were expecting, but it didn't dampen their enthusiasm the afternoon I saw it. The front rows were filled with girls about eleven to fourteen years old who held their arms as though to bathe in the screen-image and screamed like a surge of seagulls in a high wind. The secret of the picture's appeal to non-fans is simple: it's funny. Alun Owen's screenplay has captured and probably improved on the Liverpudlians' natural irreverence. And Richard Lester, who directed Peter Sellers in The Running, Jumping and Standing Still Film, has combined sight gags with the sort of rough immediacy that is found in the best cinema-verité films. Part fact and part fiction, A Hard Day's Night presents a day in the life of the Beatles -- not a real day, but a true-to-life day, with Paul, George, John and Ringo playing variations on themselves.

They emerge as four talented zanies, something like the Marx Brothers with their disdain for society. During a ride in an English train compartment, a pompous Colonel Blimp type tells them: "I fought the war for your sort." "I'll bet yer sorry ya won," is the Beatle reply. Clearly the Beatles have something in common with the angry young kitchen-sink heroes of recent British films, though they appear to be anarchists, not socialists. "Are you a Mod or a Rocker?" a journalist ask in a hilarious interview sequence. "I'm a mocker," says the Beatle, and it's quite true. They don't take anything seriously, not even their own success. When the fan mail arrives, their fatherly manager (played by Norman Rossington) orders them to stay in like good little stars to answer it, so naturally they skip out for a little fun. And when a makeup girl comes around before the television show, John (or was it George?) says: "I hope you're not going to interfere with my basic rugged image." That basic image, as social commentators have noted, is not only kooky and irreverent, but also sexually ambivalent, just like the long-haired teenagers of both sexes who worship them. There is, as well, something funny about people looking alike. It's one of the enduring sources of humor, and Lester, the director, puts it to good use. These teenage rages always seem to focus on a singer or music-maker, probably because of the enduring association of love and music. Comics just don't cause faintings and riots in the street. Frankie sent them with sentiment, Presley communicated a doing-what-comes-naturally kind of frenzy, and the Beatles project a fun-loving cheekiness that is strangely innocent. "This won't last and we know it," says John Lennon, the writer of the group. He could be wrong. About: Wendy Michener.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: |

||

|

|