|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The News Today

June 18, 2022 Happy 80th Birthday Paul!!

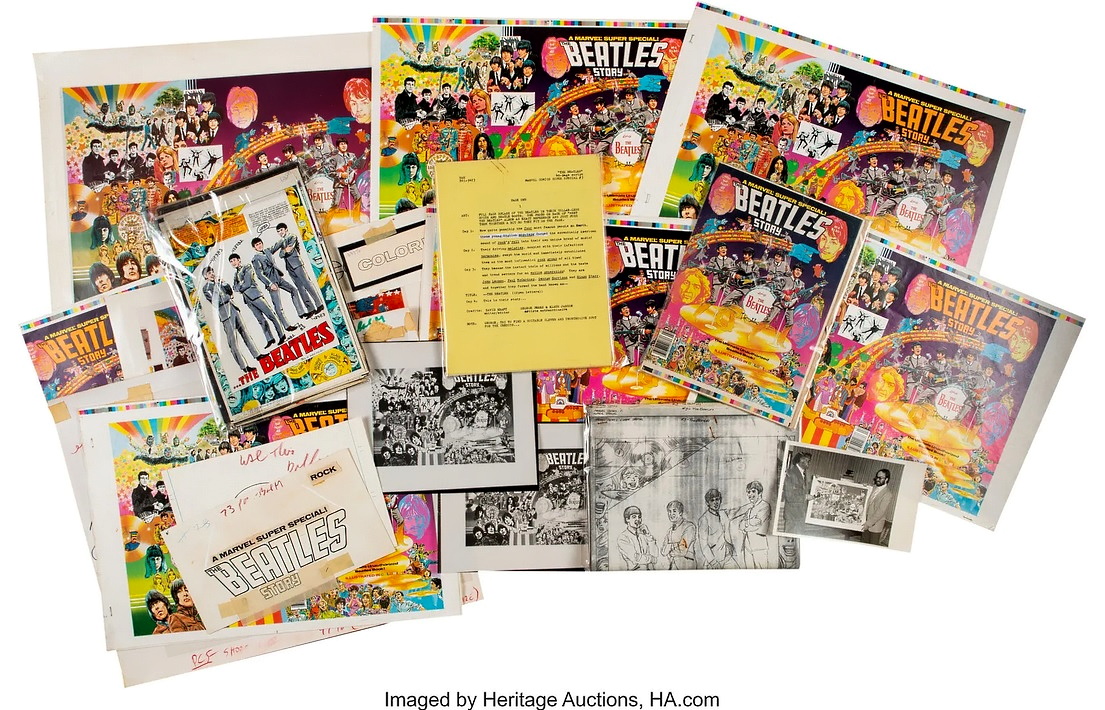

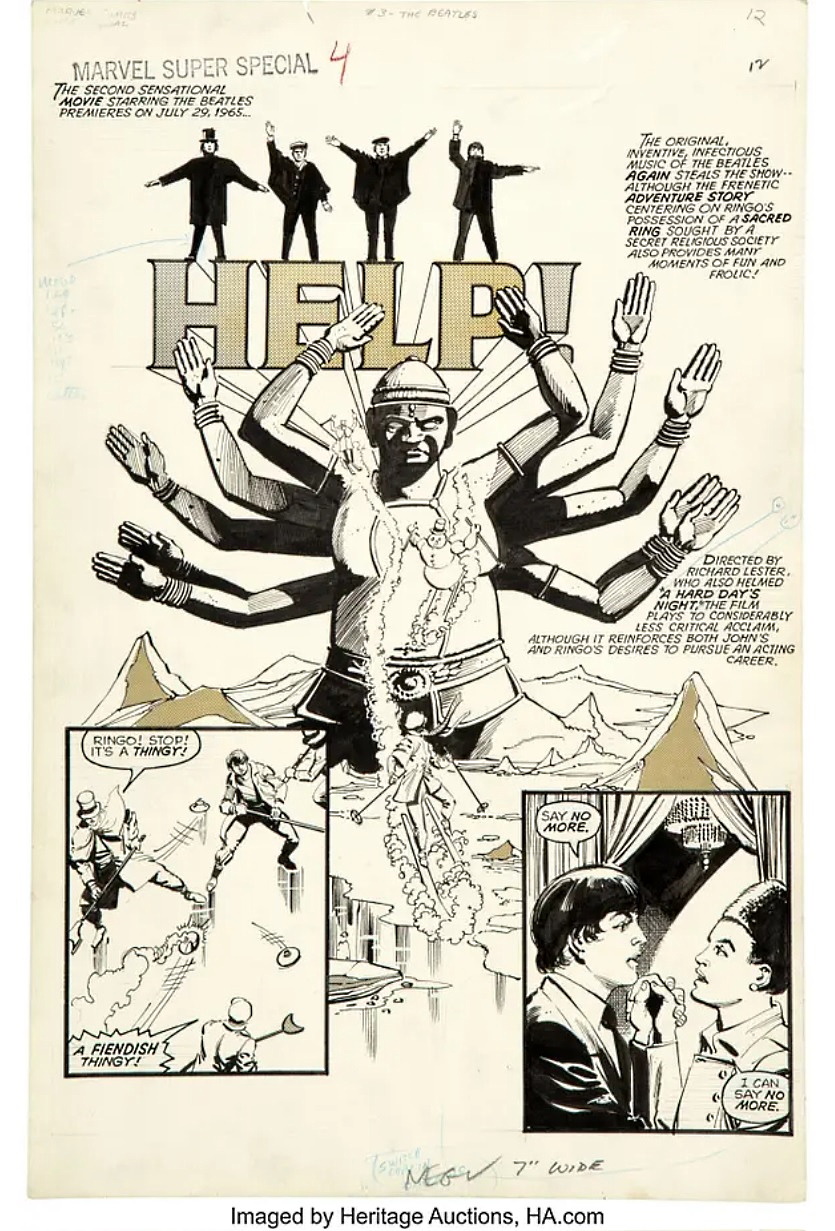

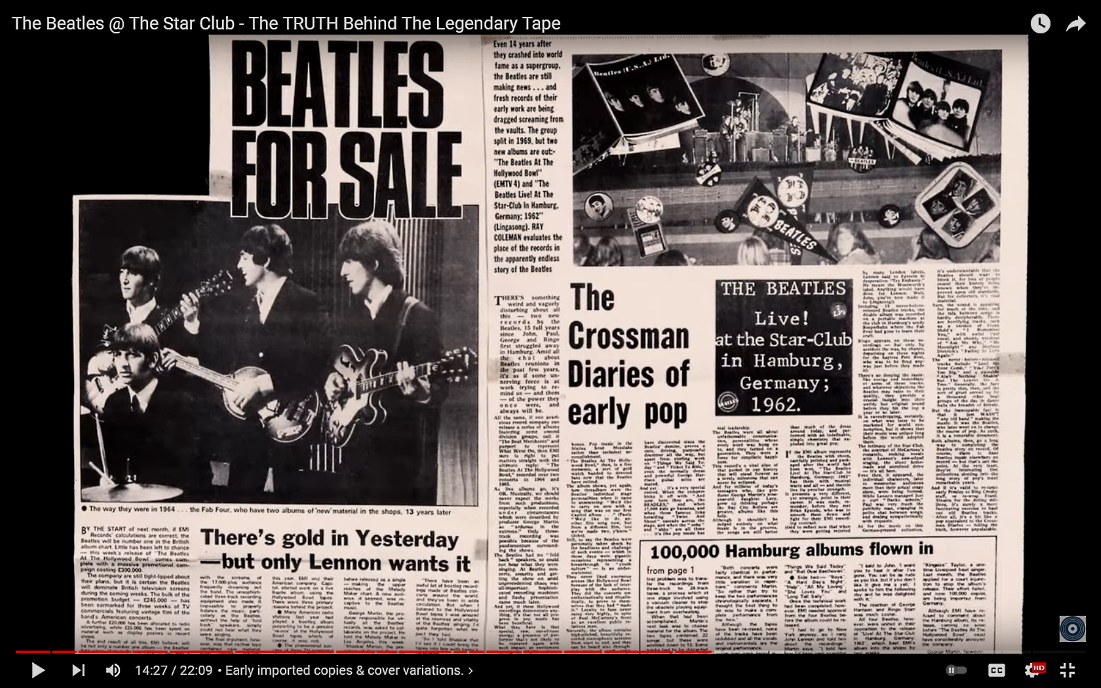

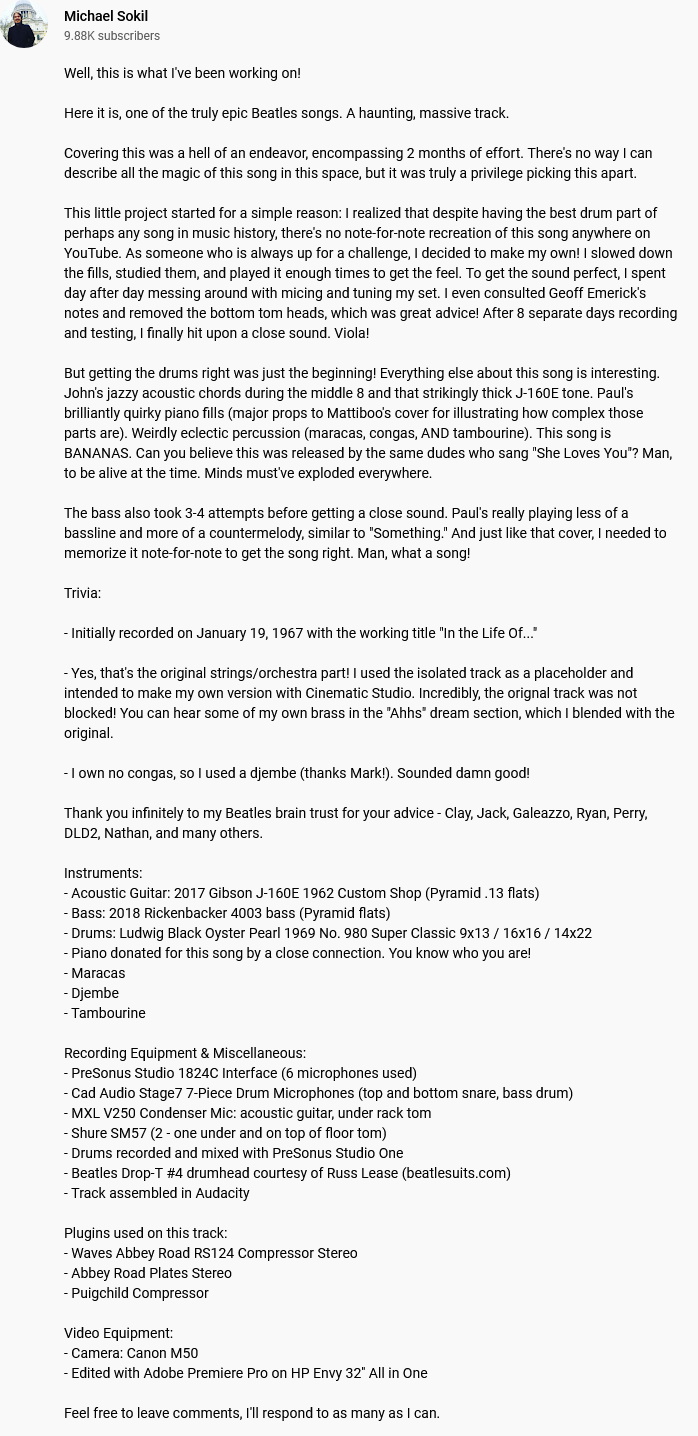

Paul McCartney performing "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da" with the fabulous Hot City Horns Video by Michael Sokil  June 17, 2022 It's a day early, but what the heck...HAPPY BIRTHDAY PAUL!! video by Michael Sokil Every George Pérez Original Art Page For Marvel Beatles Comic For Sale by Rich Johnston for Bleeding Cool Oh this is insane! Beatlemania! As part of a massive auction of premium comic books and original artwork at Heritage Auctions, they are selling a lot of work by the late great George Pérez, including this classic Batman splash currently getting bids of up to $55,000 so far. But one lot is absolutely incredible and I heard his inker Klaus Janson talking about this at Lake Comic Con Art festival last month. The Complete Beatles Story written by David Anthony Kraft that they created together for Marvel in the seventies. All thirty-nine pages in one lot, currently receiving bids totalling $9,900 which is a bargain for anyone's money. I don't know if George Pérez fans or Beatles fans will get this but someone will… also that means we get to read the whole thing in its original uncoloured artwork. Here is the listing.

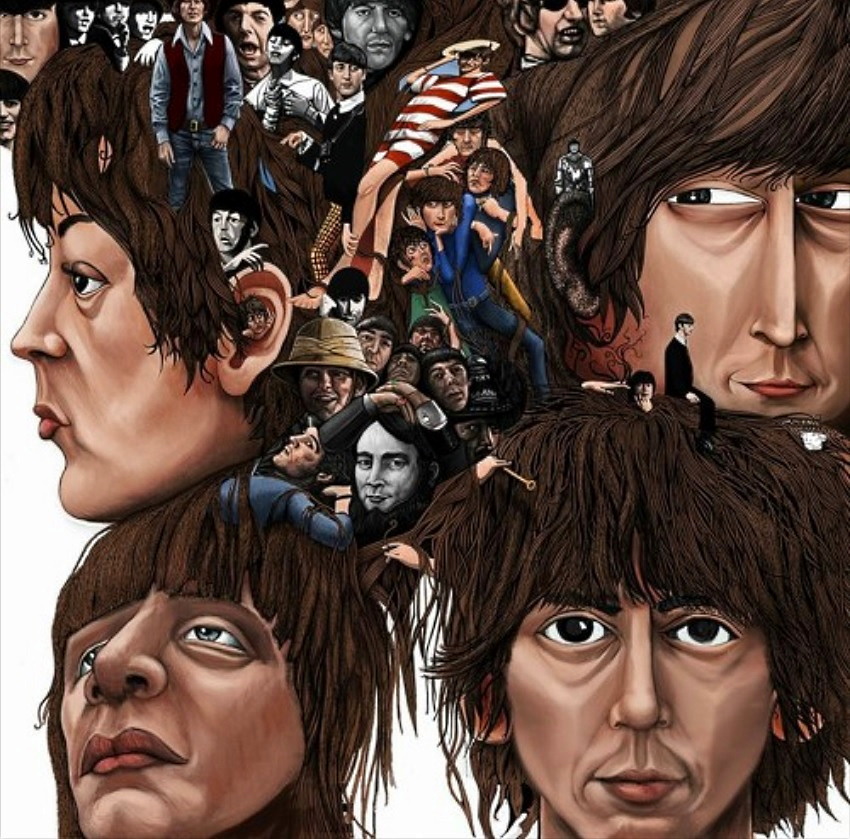

George Pérez and Klaus Janson Marvel Comics Super Special #4 The Beatles Story Complete 39-Page Story Original Art, Production Materials, and Ephemera Memorabilia Box Lot (Marvel, 1978). The Beatlemania heyday may have been the '60s, but the group's legend only seemed to grow during the '70s and beyond. When Marvel featured the Fab Four in a complete issue of its new hit magazine, Marvel Comics Super Special in 1978, legions of fans responded. There had been other authorized comic book appearances by the world's most popular band, but nothing before or since this masterpiece rivaled it for size and content. Rendered by the artistic duo of George Perez and Klaus Janson, it featured 39 pages of four-color majesty, a visual history of the Fab Four, all the more glorious in its magazine-sized format. Conte crayon and Zipatone over graphite on Bristol board with image areas of approximately 10.5" x 15". There are stat paste-up text corrections, and whiteout art/text corrections. The pages average Very Good condition. As a huge bonus, this lot comes with a "B-Side" too – piles of various production materials and photographs! One photo features Stan "The Man" Lee and writer David Anthony Kraft (aka DAK) posing with the original cover art (which is not included). There is a copy of Kraft's typed script for the issue, photocopies of the Pérez raw pencils, the printer's reference color guides, an unbound/untrimmed set of printer's proof pages of the entire issue (text articles and all), the production logo used (part hand-lettered, part stat), multiple sets of prints of the color separations for the cover, two full-color prints of the final cover design, and more! It's a treasure trove of fantastic original art and memorabilia. Yeah, Yeah, Yeah! Items are on average in Very Good condition.

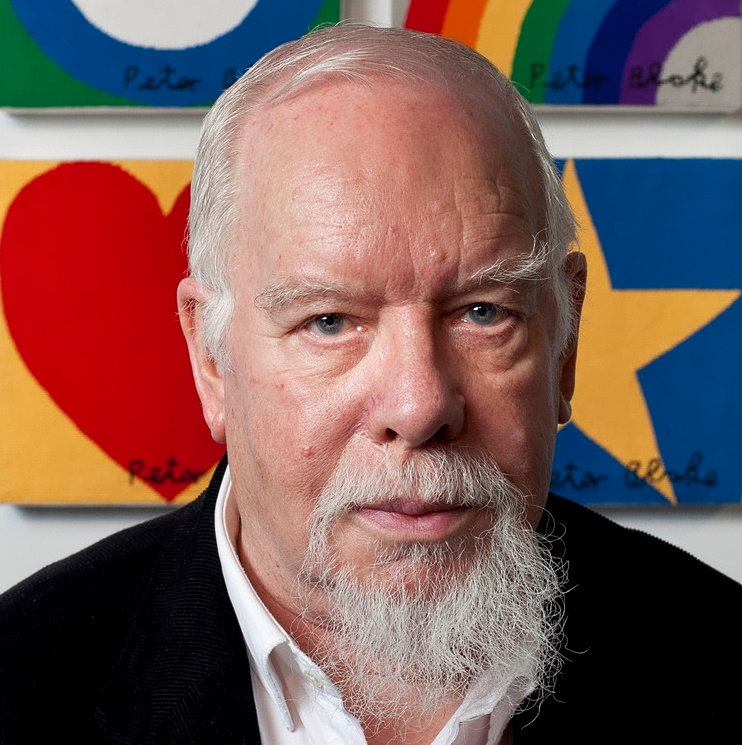

Click here to view the entire comic book art work that is in this collection.  June 15, 2022 ‘The Beatles? I was more a fan of the Beach Boys’: Peter Blake at 90 on pop art and clubbing with the Fab Four by Jonathan Jones for The Guardian

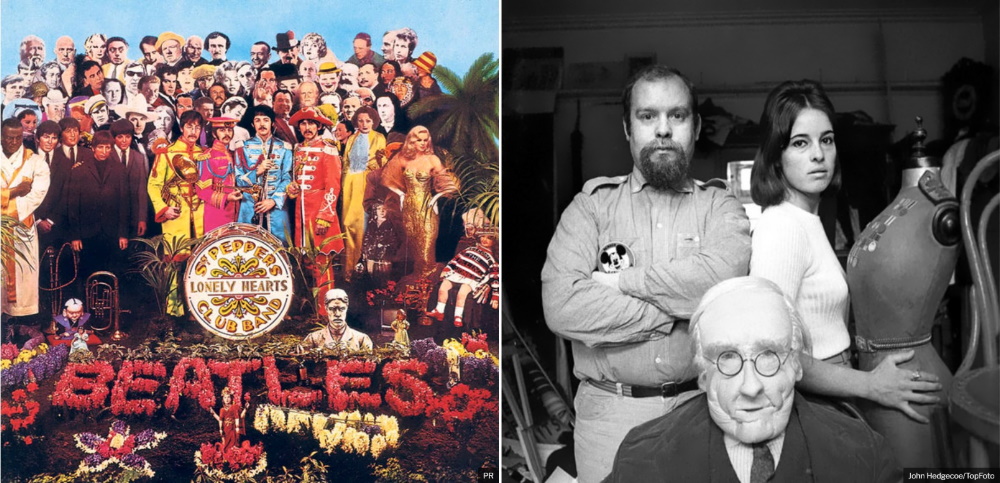

Peter Blake’s wife, Chrissy, is lovingly protective of her husband, who will turn 90 on 25 June. I don’t know where she has been listening, but when she hears the word “Beatles” she pops into the upstairs lounge where he is ensconced in an armchair. “Let this be the only article in the last 55 years that doesn’t mention the Beatles,” she pleads. Some hope. Blake, with his first wife, the artist Jann Haworth, designed perhaps the most famous album cover in history for the Fab Four’s conceptual 1967 spectacular Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band: ever since, his fame as an artist has been inextricable from this one crazy image of John, Paul, George and Ringo posing in lurid neo-Edwardian garb among a crowd of famous and less famous heroes. Chrissy is, of course, right – it’s not as if this was the be-all and end-all of Blake’s vision. To celebrate his birthday, he has an exhibition at the Waddington Custot gallery in London, of a passion to which he has dedicated four decades: visualising Dylan Thomas’s “play for voices”, Under Milk Wood. Blake has recreated the characters’ funny, filthy dreams in tender watercolours and portrays all the people of the imaginary village Llareggub with photographic clarity, as if it were a documentary instead of a dream play. He brings the same innocence and sincerity to Under Milk Wood as he has done to all his crazes. In fact, we weren’t discussing Sgt Pepper when Chrissy got worried. We were talking about Blake’s love of doo-wop, the harmonious genre of male singing invented in the 1940s US that fed into modern pop music. “I loved people like the Four Freshmen, the Hi-Lo’s and Kirby Stone Four. Doo-wop groups. Out of that came the Beach Boys and the Lettermen,” says Blake. These were his personal music passions, as well as bebop and R&B – “Bo Diddley I was an enormous fan of.”

And the Beatles? He pauses reflectively.

“I was interested in them. I’ve never been an enormous fan of the Beatles like I am of the Beach Boys. It’s a dangerous thing to say, I hope that won’t be your headline: ‘Peter Blake doesn’t like the Beatles.’”

But this is not a criticism of the Beatles so much as a reflection on what it is to be a “fan”, which Blake is: and it is at the very heart of his work. He is a fan who has got to know his idols, which led him from making a fan’s image of the Beach Boys in 1964 to collaborating with Brian Wilson. He has also had a friendly working relationship with the Who since he first met them in the early 60s: he has designed two of their album covers.

“Their manager [Kit Lambert] said that they needed a change of direction and he was going to call them The Pop Art Group. He researched pop art and made a look with the union jack jacket. I think Roger [Daltrey] had a belt with black and white stripes which I had originally appropriated from Jasper [Johns]. And then the badges. They designed that Who look on the work I was doing.”

Blake’s version of pop art is warm, affectionate and respectful. He has never been a lofty artist standing above mass culture. His idiosyncratic tastes in comics, fairgrounds, tattoos, wrestling, toy shops, badges and the union jack played a crucial part in the blend of modernity and nostalgia that shaped a new culture in 1960s Britain.

Blake started using pop imagery in the mid-50s as a student at the Royal College of Art. Born in Dartford, Kent, in 1932, he studied graphic design at Gravesend Technical College, then did his national service before starting on the Royal College painting course, where senior students were encouraged to paint what they liked.

“I suppose at that point my life appeared: I started to paint autobiographically, and it’s pictures of my little brother and cousin with badges on, and my sister and me reading comics. My life at that point was popular culture. In the evenings I would go to professional wrestling … I went to Bexleyheath Drill Hall, that was the local venue. It was packed every week. The first fight I saw was Mick McManus who went on for years as one of the stars. Pop art and popular culture are quite separate entities. I could be a pop artist and not be interested in popular culture, but as it happens I am.”

In 1961, Blake painted a self-portrait that is one of the great works of pop art. He stands in a suburban garden, staring forwards, like the clown Gilles who was painted by the French Rococo artist Jean-Antoine Watteau. Except, instead of a clown outfit, Blake is wearing denim and trainers. He is holding an Elvis magazine and sports badges on his jacket.

“It was a very early embryonic collection of badges. It’s been said that they emblazoned my interests and my likes but it wasn’t particularly that – they were the only ones I had. I didn’t know who Adlai Stevenson (the 1960 Democratic presidential candidate) was. It was just what I had. Since then I have collected hundreds. In 1961, a man wouldn’t have worn badges. But a child would have done, a little boy would have done. So it is a boy-like figure, but a man. Also wearing denim in 61 was quite early, and to be wearing trainers was ahead of its time.”

This is a remarkably sensitive reading of his own Self-Portrait With Badges. It is a portrait of the birth of youth culture itself. As he puts it, a “man” in 1961 was not supposed to wear badges or denim or trainers. A man was meant to be suited and serious.

I ask about the shirt, which looks like a Fred Perry. “I was pretty much a mod at that point. So it’s a mod shirt, yeah.”

“You’ve still got that red shirt,” says Chrissy.

Yet Blake’s definition of popular culture was not confined to the young and fashionable. “I was very interested in music halls. I called my Royal College thesis Don’t Point, It’s Nude, and it was about the nude shows that were being introduced into music halls by Paul Raymond. I was going every week to the halls to see Max Wall, Max Miller and all the greats. The music hall was dying. You would go and see a comedian in the first house and there would be 30 people. Raymond thought nudity would revive the music hall – in fact it killed it a little bit quicker. I was writing it in 1956: there were some great shows that year where they could make the six become sex and say: “It’s a happy nineteen fifty sex.” I loved all that. So, yes, I’ve always been interested in the halls, and things like corn dollies and the actual popular arts.”

The folk art Blake loves has always fuelled him. His early works include two buxom fairground women, painted naively on wood and decorated with collage and glass beads. One is Loelia, World’s Most Tattooed Lady, the other Siriol, She-Devil of Naked Madness. Blake’s fascination with the quirky side of popular culture, from the music halls to these sideshow hoardings, is mirrored perfectly in the pop songs of the 60s. The Beatles’ Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite! takes its title from an 1843 circus poster that John Lennon found in an antique shop.

“I’ve been a friend of them, certainly. I met them in 1963. And … no, I am a fan, I am a fan.” Blake is warming to the Beatles.

His friendship with the band began when they came to London to appear on a TV show and Blake was invited to sit in, through an art director friend from Liverpool who had been telling him about this great new group.

“Billy Fury was top of the bill and two boys who had just left the Shadows; there was a female singer called Billie Davis. The Beatles did the opening song Please Please Me, I think. I sat in the audience – just me, nobody else, and that’s when we first met and our friendship started.”

The Beatles were still innocents when he next met them at a gig – or at least John, George and Ringo were. “We went back to the hotel with George and John and Ringo, but no Paul. We sat in the foyer and a man came up and said: ‘Would you sign this for my daughter?’ But people weren’t bothered otherwise and we had tea. Then John said: ‘Do you know any nightclubs? We don’t really know London and we’ve never been clubbing here.’ The week before I had been taken to a place called The Crazy Elephant, and I said: ‘I’m not a member, but we could try it.’ Joe Tilson (a fellow pioneer pop artist) was with us, too, and Joe had a second world war Jeep so we all piled into it and went to The Crazy Elephant. But the doorman said: ‘No, sorry mate, you’re not a member.’ They were playing a Beatles song and John said: ‘Well that’s our song, I’m a Beatle.’ He didn’t believe him. But a voice from around the corner said: ‘Can you let them in? They’re friends of mine.’ We went in, and it was Paul. He was already there with Jane Asher.”

It was an older and more artful group who went into the studio later in the decade to record Sgt Pepper.

“Normally at this point I clam up, but I’ll tell you as best I can,” Blake says. “They had already got a design group called The Fool to do a cover, but the art dealer Robert Fraser talked to Paul and said: “Look, this isn’t a very good cover – it’s psychedelic but there are a lot of other psychedelic things going on – that swirly pink and orange and green stuff – why don’t we use one of the artists in my gallery and make a fine art cover?”

So Blake was commissioned to create a cover that was truly a work of art, yet would be owned in homes all over the world: pop art as popular art.

“The album name was already decided. They were having the uniforms made. They had a vague idea of it being like a brass band, Black Dyke Mills Band or something like that.”

As the Beatles worked on the songs, Blake developed the idea for the cover.

“I did it with my first wife, Jann, and one of us proposed that we could use the idea of a flower clock: in Edinburgh there’s a beautiful one. It slowly evolved into the idea that they had just done a gig, they were in a park and a group of their fans were getting behind them for a photograph. Various ideas came from the Beatles, and others from us. We employed a fairground painter to do the drum.”

To construct the image, they blew up collaged figures to lifesize and posed the band in front, with a real flower arrangement.

“Looking at it from the side it’s a wall, with things fixed to the wall, and then out comes a little platform that they’re standing on, then sloping forwards from the platform is the flowerbed. All the cut outs are made of plywood, then the photographs are stuck to them and hand coloured. I had recently done work for Madame Tussauds, so they lent us their waxworks of the Beatles and Sonny Liston, who I was a great fan of, and Diana Dors. So it’s a mixture of flat cut outs, waxworks and then this platform and the drum.”

On the morning they were to shoot the photograph, everything was perfect. “Clifton Nurseries came in, did the flowerbed, and then the Beatles called and said we can’t do it today – they were finishing off Lovely Rita. So all the flowers went back.” A new day was arranged. “On that day they arrived, put their uniforms on, and Michael Cooper came and took the photograph. Now I would do it on the computer!”

The people in the crowd were partly chosen by the Beatles, but others reflect Blake’s and Haworth’s enthusiasms. Next to the instantly recognisable Bob Dylan is the less familiar face of Simon Rodia, an Italian “outsider artist” who built the wondrous Watts Towers in Los Angeles from wire, shards of glass and other found stuff.

Blake’s admiration for Rodia, ever since he made a pilgrimage to Watts in 1963, is another example of his unaffected, unironic love of popular art. We compare notes of our trips to see the Towers – he went a couple of years before the Watts riots, I went many decades later – but Rodia’s glittering vision is still a joy on the troubled skyline.

The furniture in this room, he says, is a homage to Rodia, with glittering shards of glass embedded into chests and tabletops. This belief in outsider art makes Blake a uniquely generous figure who defies boundaries of taste and cultural value. The kids in his pioneering 1954 pop canvas Children Reading Comics are sincerely enjoying them. This is a million miles from fellow pop artists such as Richard Hamilton or Roy Lichtenstein who looked at the consumer and media age with cool irony, perhaps even contempt.

The New York pop painter Roy Lichtenstein turned comic strips into abstract paintings. But, says Blake: “My theory about Lichtenstein is that he didn’t actually like comic books.

“They were good I think, but they weren’t kind: they weren’t kind to comic books. I think that’s the difference between Lichtenstein and myself – he was making a product and I was a fan.”

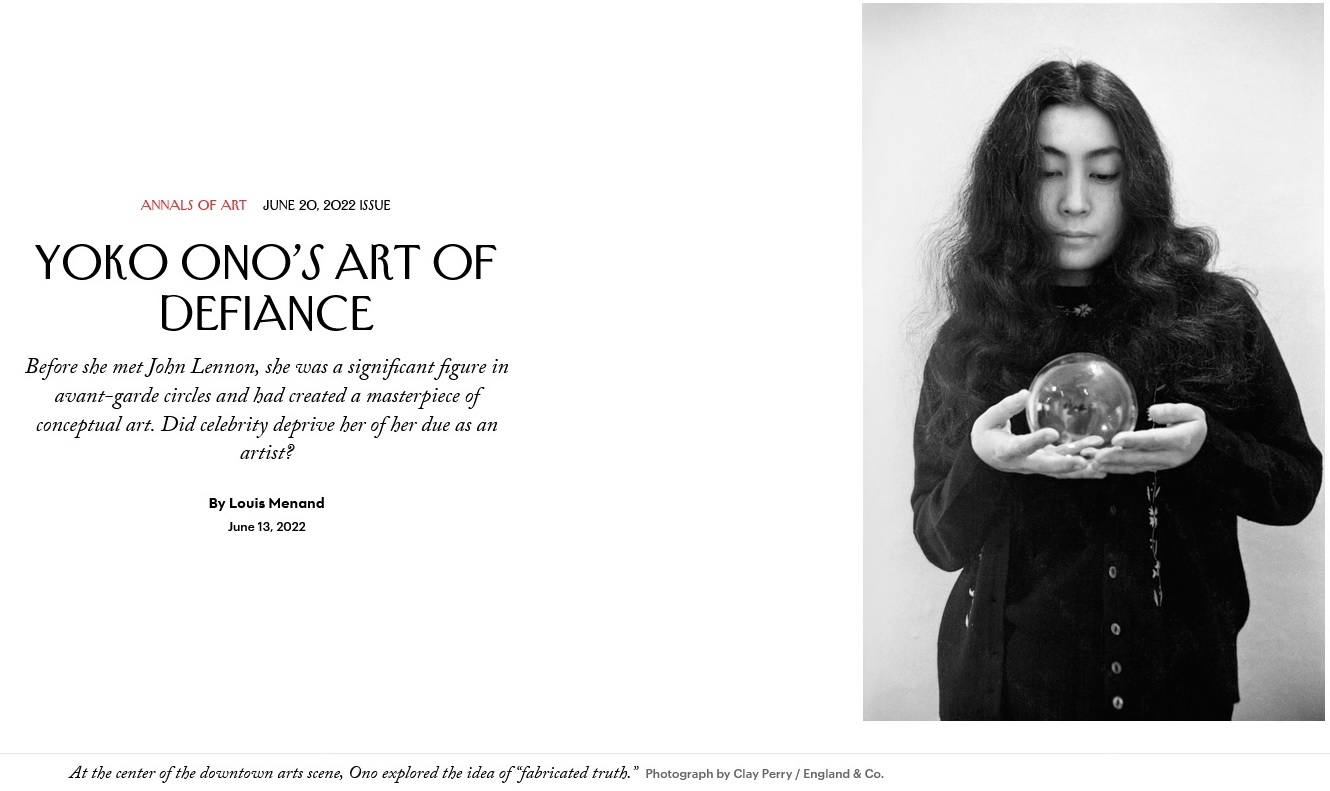

Peter Blake: Under Milk Wood is at Waddington Custot, London, until 23 July.  June 14, 2022 The New Yorker's fascinating write-up on Yoko Ono by Louis Menand

On March 9, 1945, an armada of more than three hundred B-29s flew fifteen hundred miles across the Pacific to attack Tokyo from the air. The planes carried incendiary bombs to be dropped at low altitudes. Beginning shortly after midnight, sixteen hundred and sixty-five tons of bombs fell on the city.

Most of the buildings in Tokyo were constructed of wood, paper, and bamboo, and parts of the city were incinerated in a matter of hours. The planes targeted workers’ homes in the downtown area, with the goal of crippling Japan’s arms industry. It is estimated that a million people were left homeless and that as many as a hundred thousand were killed—more than had died in the notorious firebombing of Dresden, a month earlier, and more than would die in Nagasaki, five months later. Crewmen in the last planes in the formation said that they could smell burning flesh as they flew over Tokyo at five thousand feet.

That night, Yoko Ono was in bed with a fever. While her mother and her little brother, Keisuke, spent the night in a bomb shelter under the garden of their house, she stayed in her room. She could see the city burning from her window. She had just turned twelve and had led a protected and privileged life. She was too innocent to be frightened.

The Ono family was wealthy. They had some thirty servants, and they lived in the Azabu district, near the Imperial Palace, away from the bombing. The fires did not reach them. But Ono’s mother, worried that there would be more attacks (there were), decided to evacuate to a farming village well outside the city.

In the countryside, the family found itself in a situation faced by many Japanese: they were desperate for food. The children traded their possessions to get something to eat, and sometimes they went hungry. Ono later said that she and Keisuke would lie on their backs looking at the sky through an opening in the roof of the house where they lived. She would ask him what kind of dinner he wanted, and then tell him to imagine it in his mind. This seemed to make him happier. She later called it “maybe my first piece of art.”

Like any artist, Ono wanted recognition, but she was never driven by a desire for wealth and fame. Whether she sought them or not, though, she has both. Her art is exhibited around the world: last year at the Serpentine, in London (“Yoko Ono: I Love You Earth”); this year at the Vancouver Art Gallery (“Growing Freedom”) and the Kunsthaus in Zurich (“Yoko Ono: This Room Moves at the Same Speed as the Clouds”). She began managing the family finances after she and her husband John Lennon moved to New York, in 1971, and she is said to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars today.

There is no question that museums and galleries mount these shows and people go to see them because Ono was once married to a Beatle. On a weekday not long ago, I saw the Vancouver show, which occupied the whole ground floor of the museum, and there was a steady stream of visitors. None of the artists and composers Ono was associated with in the years before she married Lennon enjoys that kind of exposure today.

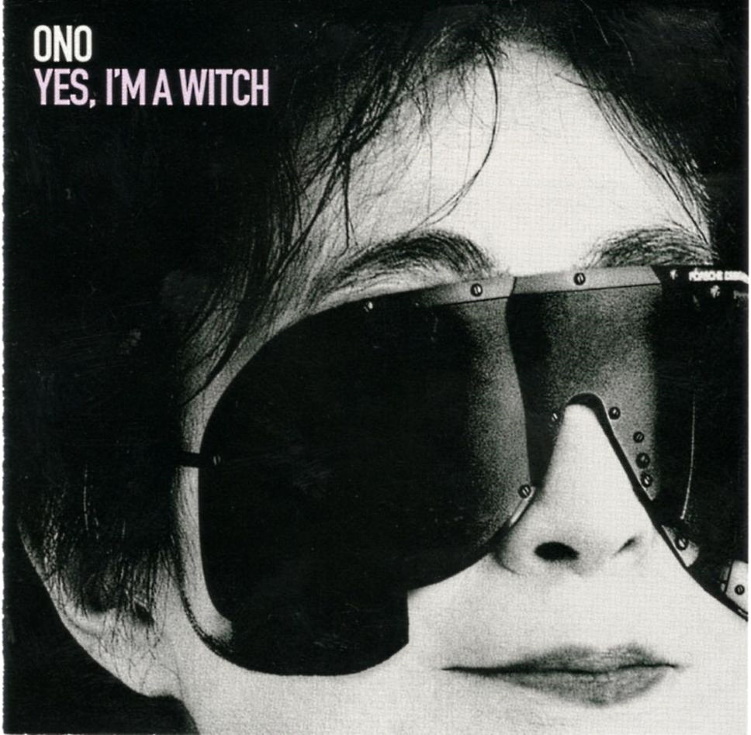

Ono may have leveraged her celebrity—but so what? She never compromised her art. The public perception of her as a woman devoted to the memory of her dead husband has made her an icon among the kind of people who once regarded her as a Beatles-busting succubus. Yet the much smaller group of people who know about her as an artist, a musician, and an activist appreciate her integrity. No matter what you think of the strength of the art, you can admire the strength of the person who made it.

The most recent Ono biography is “Yoko Ono: An Artful Life,” by Donald Brackett, a Canadian art and music critic. He didn’t talk to Ono, and there’s not much in the way of new reporting in his book. The result feels somewhat under-researched. He dates the great Tokyo air raid to 1944, for example, and he gives the impression that Ono spent the night in the bunker with her family. Still, he is an enthusiastic writer, sympathetic to his subject (not so much to Lennon), and alive to the attractions of an unusual person and an unusual life.

Ono has talked about her parents as being emotionally distant. Her mother was a Yasuda, a member of the family that founded the Yasuda Bank, later Fuji Bank, and that owned one of the four largest financial conglomerates in Japan. Ono’s father worked at the Yokohama Specie Bank, which became the Bank of Tokyo after the war, and was frequently posted to foreign branches. He was in San Francisco when Yoko was born; she did not lay eyes on him until she was three. When Tokyo was firebombed in 1945, he was in Hanoi.

Ono received an exceptional education. Beginning when she was very young, she was tutored in Christianity (her father was a Christian; there were not many in Japan), Buddhism, and piano. She attended a school known for its music instruction; she was once asked to render everyday sounds and noises, such as birdsongs, in musical notation. After the war, she attended an exclusive prep school; two of the emperor’s sons were her schoolmates. And when she graduated she was admitted to Gakushuin University as its first female student in philosophy.

She left after two semesters. She said the university made her feel “like a domesticated animal being fed information.” This proved to be a lifelong allergy to anything organized or institutional. “I don’t believe in collectivism in art nor in having one direction in anything,” she later wrote. A classmate offered a different perspective: “She never felt happy unless she was treated like a queen.”

Ono may also have dropped out because her parents had moved to Scarsdale when her father’s bank posted him to the New York City branch. Ono soon joined them, and, in 1953, entered Sarah Lawrence, in Bronxville, less than half an hour away. Sarah Lawrence was an all-women’s college at that time and highly progressive, with no requirements and no grades. Ono took classes in music and the arts, but she seems not to have fitted in. A teacher remembered her as “tightly put together and intent on doing well. The other students were more relaxed. She wasn’t relaxed, ever.”

As non-prescriptive as it was, Sarah Lawrence triggered her allergy. It was “like an establishment I had to argue with and I couldn’t cope with it,” she complained. She now decided that she needed to get away from her family. “The pressure of becoming a Yasuda / Ono was so tremendous,” she said later. “Unless I rebelled against it, I wouldn’t have survived.” Somewhere (stories differ) she met Toshi Ichiyanagi, a student at Juilliard, and in 1956 she dropped out of college, got married (her parents weren’t thrilled), and moved to Manhattan. She began supporting herself with odd jobs. She lived in the city for most of the next ten years.

Not long before leaving Sarah Lawrence, Ono published in a campus newspaper a short story called “Of a Grapefruit in the World of Park.” It’s about some young people trying to decide what to do with a grapefruit left over from a picnic. The allegory is a little mysterious, but it’s clear what the grapefruit represents. The grapefruit is a hybrid, and so is Yoko Ono.

It’s easy to feel that there is an amateurish, “anyone can do this” quality to her art and her music. The critic Lester Bangs once complained that Ono “couldn’t carry a tune in a briefcase.” But the look is deliberate. It’s not that she wasn’t well trained. She learned composition and harmony when she was little, and she could write and read music, which none of the Beatles could do. At Sarah Lawrence, she spent time in the music library listening to twelve-tone composers like Arnold Schoenberg.

She grew up bilingual and was trained in two cultural traditions. She went to secondary school and college in Japan in a period of what has been called “horizontal Westernization,” when artistic and intellectual life was rapidly liberalized as the nation tried to exorcise its militarist and ultranationalist past. Ono and her friends read German, French, and Russian literature in Japanese translation, and the young philosophers they knew were obsessed with existentialism. She also knew Japanese culture. One of the ways she supported herself in New York was by teaching Japanese folk songs and calligraphy. She knew waka and Kabuki. She was therefore ideally prepared to enter the New York avant-garde of the nineteen-fifties, because that world was already hybrid. Its inspirations were a French artist, Marcel Duchamp, and an Eastern religion, Zen Buddhism.

The personification of those enthusiasms was the composer John Cage—a student of Schoenberg, a devotee of Eastern thought, and an idolater of Duchamp. Ono got to know Cage through her husband, who took an evening class that Cage taught at the New School. Although Ono didn’t take the class, artists who would be part of her circle did, the best known of whom was Allan Kaprow, the creator of the Happening.

Cage didn’t expect his students to imitate his own work. He said that one of the most important things he learned from teaching the class was something Ichiyanagi had said to him in response to a suggestion: “I am not you.” But he encouraged experimentation.

And the students duly experimented. A representative piece for the class is “Candle-Piece for Radios,” by George Brecht. Radios are placed around a room in the ratio of one and a half radios per performer. At each radio is a stack of cards with instructions printed on them, such as “volume up,” “volume down,” and “R” or “L,” denoting the direction the radio dial is to be turned. Each performer is given a lit birthday candle, and, on a signal, begins going through the decks, card by card, using any available radio. The piece ends when the last candle goes out.

This is how Happenings work. They are not “anything goes” performances; most Happenings (there are some exceptions) have a script, called an “event score.” Each participant follows specific instructions about what actions to perform and when.

In 1960, Ono found a loft at 112 Chambers Street and rented it for fifty dollars and fifty cents a month. It was a fourth-floor walkup, without heat or electricity, and the windows were so coated with grime that little light got in, though there was a skylight. The furnishings consisted mostly of orange crates and a piano. Ono turned this into a combination living and performance space. Together with La Monte Young, a composer and musician (he was a developer of the drone sound used by the Velvet Underground on some of their songs), she organized a series of concerts and performances. From December, 1960, to June, 1961, eleven artists and musicians performed in the loft, usually for two nights each. Ono said that these concerts were sometimes attended by two hundred people. Cage came, and so did Duchamp. Suddenly, she was at the center of the downtown arts scene.

At some sessions, Ono herself “performed” art works. One consisted of mounting a piece of paper on the wall, opening the refrigerator and taking out food, such as Jell-O, and throwing it against the paper. At the end, she set the paper on fire. (Cage had advised her to treat the paper with fire retardant first so that the building would not burn down.) The art work consumes itself.

The New York art world of 1960, even in its most radical downtown incarnation, was male-dominated. Of the eleven artists who headlined events in the Chambers Street series, only one was a woman. To Ono’s annoyance, Young was credited as the organizer and director of the series. She was identified as the woman whose loft it was.

She was even more annoyed when she learned that a man who had attended some of the concerts was planning to mount a copycat series in his uptown art gallery. The gallery, on Madison Avenue, was called the AG Gallery, and the man was George Maciunas.

Maciunas came to the United States from Lithuania in 1948, when he was a teen-ager, and spent eleven years studying art history. Then, around 1960, he set out to reinvent art by taking it off its pedestal. Duchamp and Cage were his great influences. (Maciunas is the subject of a compelling and entertaining documentary that resurrects the New York art underground of the nineteen-sixties, called “George: The Story of George Maciunas and Fluxus,” directed by Jeffrey Perkins.)

Ono was mollified when Maciunas offered her a show. He never had money. This did not prevent him from renting property, having a telephone, or anything else. He just didn’t pay his bills. By the time Ono’s show was mounted, in July, 1961, the gallery could be visited only in daylight hours, because the electricity had been turned off. Her show “Paintings and Drawings by Yoko Ono” was the gallery’s last.

Ono was present to guide visitors through the show, explaining how the pieces were supposed to work, because some of the art required the viewer’s participation—for example, “Painting to Be Stepped On,” a piece of canvas on the floor. That work, like a lot of Duchamp’s, might seem gimmicky. But, like Duchamp’s, there is something there to be unpacked. “Painting to Be Stepped On” resonates in two traditions. It alludes to the widely known photographs, published in the late nineteen-forties in Life and elsewhere, of Jackson Pollock making his drip paintings by moving around on a canvas spread on the floor. Those photographs, representing painting as performance, inspired artists (including Kaprow) for decades.

The second context, identified by the art historian Alexandra Munroe, is Japanese. In seventeenth-century Japan, Christians were persecuted, and one way to identify them was to ask them to step on images of Jesus and Mary. The procedure was called fumi-e—“stepping on.” People who refused could be tortured and sometimes executed. “Painting to Be Stepped On” is a grapefruit.

In the fall of 1961, Ono gave a concert in Carnegie Recital Hall, a venue that was adjacent to the main hall and that seated about three hundred. Maciunas, now a friend, helped design the show. According to the Times, the place was “packed.” But accounts are so various that it’s hard to tell, exactly, what happened.

Onstage, twenty artists and musicians performed different acts—eating, breaking dishes, throwing bits of newspaper. At designated intervals, a toilet was flushed offstage. A man was positioned at the back of the hall to give the audience a sense of foreboding. A huddle of men with tin cans tied to their legs attempted to cross the stage without making noise. The dancers Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown sat down and stood up repeatedly. According to the Village Voice, the performance finished with Ono’s amplified “sighs, breathing, gasping, retching, screaming—many tones of pain and pleasure mixed with a jibberish of foreign-sounding language that was no language at all.”

This was the kind of art that Maciunas had in mind. It used everyday materials. It had humor (the flushing toilet), meaning that it did not take itself too seriously. And it was anti-élitist. Anyone could do it. Around the time of Ono’s concert, Maciunas came up with a name for this kind of art: Fluxus. When he told Ono, she said it was a mistake to give the art a group name. That is how the Japanese art world worked; every artist was identified with a group. She didn’t want to belong to a group.

But Maciunas was an inveterate organizer—a problem, since he happened to be working with avant-garde artists, the kind of people who don’t like to be organized. For years, he tried to herd those cats. He opened FluxShop, where Fluxus art—mostly cheap plastic boxes filled with odds and ends—could be purchased. (Walk-in business was not brisk.) At one point, he made plans to buy an island and build a self-sufficient Fluxus community on it.

The island venture did not pan out, but Maciunas would finally realize his idea by buying and renovating abandoned buildings—more than twenty of them—in downtown Manhattan for artists to live and work in. The enterprise ruined him. He was sued by the tenants because the renovations were not up to code and the lofts could not pass inspection, and he was badly beaten by goons hired by one of his creditors. In the mid-seventies, he fled the city for a farm in Massachusetts, where he died, of cancer, in 1978. But he had given birth to SoHo. It would become, in the nineteen-eighties, the world capital of contemporary art.

Maciunas’s slogan for Fluxus was “Purge the world of ‘Europanism’!,” and at the Fluxus début, in West Germany in 1962, a grand piano was smashed to bits. Ono, who was invited but declined to attend, was not into breaking pianos. “I am not somebody who wants to burn ‘The Mona Lisa,’ ” she once said. “That’s the difference between some revolutionaries and me.” But she does share something with Maciunas. She is a utopian. She would be happy if the whole world could be a Fluxus island.

In 1962, Ono returned to Japan. She discovered that the Japanese avant-garde was even more radical than the New York avant-garde. There were many new schools. The most famous today is Gutai, which originated in Osaka in 1954. Like Fluxus, Gutai was a performative, low-tech, everyday-materials kind of art. One of the earliest Gutai works was “Challenging Mud,” in which the artist throws himself into an outdoor pit filled with wet clay and thrashes around for half an hour. When he emerges, the shape of the clay is presented as a work of art.

Ichiyanagi had returned earlier—the marriage was breaking up—and he arranged for Ono to present a concert at the Sogetsu Art Center, in Tokyo. Outside the hall, she mounted what she called “Instructions for Paintings,” twenty-two pieces of paper attached to the wall, each with a set of instructions in Japanese. The instructions resembled some of the art created by young artists in Cage’s circle in New York—for example, Emmett Williams’s “Voice Piece for La Monte Young” (1961), which reads, in its entirety, “Ask if La Monte Young is in the audience, then exit,” and Brecht’s “Word Event,” the complete score for which is the word “Exit.”

Inside the hall, with thirty artists, Ono performed several pieces, including some she had done at Carnegie Recital Hall. It’s unclear what the audience reaction was—Brackett says it was enthusiastic—but the show received a nasty review in a Japanese art magazine by an American expatriate, Donald Richie, who made fun of Ono for being “old-fashioned.” “All her ideas are borrowed from people in New York, particularly John Cage,” he wrote. This was not an attack from an uncomprehending traditionalist. This was an attack from the cultural left. Ono was traumatized. She checked into a sanitarium.

But when she came out, she picked up where she had left off. She got remarried, to Tony Cox, an American art promoter and countercultural type, and, in 1964, she published her first book, “Grapefruit,” a collection of event scores and instruction pieces:

These are like Brecht’s “Word Event,” but with a big difference. “Word Event” was intended to be performed, and artists found various ingenious ways to enact the instruction “Exit.” Ono’s pieces cannot be performed. They are instructions for imaginary acts.

In an essay in a Japanese art journal, she invoked the concept of “fabricated truth,” meaning that the stuff we make up in our heads (what we wish we could have for dinner) is as much our reality as the chair we are sitting in. “I think it is possible to see the chair as it is,” she explained. “But when you burn the chair, you suddenly realize that the chair in your mind did not burn or disappear.”

What Ono was doing was conceptual art. When conceptual artists hit the big time, at the end of the nineteen-sixties, her name was virtually never mentioned. She does not appear in the art critics Lucy Lippard and John Chandler’s landmark essay, “The Dematerialization of Art,” published in 1968. But she was one of the first artists to make it. In 1965, she came back to New York, and, in March, had another show at Carnegie Recital Hall, “New Works of Yoko Ono.” This was the New York première of her best work, a truly great work of art, “Cut Piece.”

The performer (in this case, Ono) enters fully clothed and kneels in the center of the stage. Next to her is a large pair of scissors—fabric shears. The audience is invited to come onstage one at a time and cut off a piece of the artist’s clothing, which they may keep. According to instructions Ono later wrote, “Performer remains motionless throughout the piece. Piece ends at the performer’s option.” She said she wore her best clothes when she performed the work, even when she had little money and could not afford to have them ruined.

Ono had performed “Cut Piece” in Tokyo and in Kyoto, and there are photographs of those performances. The New York performance was filmed by the documentarians David and Albert Maysles. (Brackett, strangely, says that the Maysleses’ film, rather than a live performance, is what people saw at Carnegie Recital Hall.)

In most Happenings and event art, the performers are artists, or friends of the person who wrote the score. In “Cut Piece,” the performers are unknown to the artist. They can interpret the instructions in unpredictable ways. It’s like handing out loaded guns to a roomful of strangers. Ono is small (five-two); the shears are large and sharp. When audience members start slicing away the fabric around her breasts or near her crotch, there is a real sense of danger and violation. In Japan, one of the cutters stood behind her and held the shears above her head, as though he were going to impale her.

The score required Ono to remain expressionless, but in the film you can see apprehension in her eyes as audience members keep mounting the stage and standing over her wielding the scissors, looking for another place to cut. When her bra is cut, she covers her breasts with her hands—almost her only movement in the entire piece.

Most immediately, “Cut Piece” is a concrete enactment of the striptease that men are said to perform in their heads when they see an attractive woman. It weaponizes the male gaze. Women participate in the cutting, but that’s because it’s not just men who are part of the society that objectifies women. The piece is therefore classified as a work of feminist art (created at a time when almost no one was making feminist art), and it plainly is.

But what “Cut Piece” means depends in large part on the audience it is being performed for, and Ono originally had something else in mind. When she did the piece in Japan, a Buddhist interpretation was possible. It belonged to “the Zen tradition of doing the thing which is the most embarrassing for you to do and seeing what you come up with and how you deal with it,” she said.

The piece also derived, Ono said elsewhere, from a story about the Buddha giving away everything that people ask him for until he ultimately allows himself to be eaten by a tiger. Ono was offering everything she had to strangers—that’s why she always wore her best clothes. “Instead of giving the audience what the artist chooses to give,” as she put it, “the artist gives what the audience chooses to take.”

In 1966, Ono went to London to participate in the Destruction in Art Symposium, where she performed “Cut Piece” twice. It was not read as a Buddhist text at those events. Word of mouth after the first performance led to the second one being mobbed, with men eagerly cutting off all her clothing, even her underwear. This was Swinging London; everyone assumed that the piece was about sex. After London, Ono did not perform it again until 2003, when she did it in Paris, seated in a chair. This time, she explained that the work was about world peace, and a response to 9/11.

No matter where it is performed or what reading it suggests, the piece is an experiment in group psychology. People are being invited to do something publicly that is normally forbidden—violently remove the clothing of a woman they do not know. The ones who participate can rationalize their actions by telling themselves that stripping a passive woman is not “really” what they’re doing, because it’s a work of art. But, of course, it really is what they’re doing.

And people in the audience who don’t go onstage because they find the spectacle repellent or violative can tell themselves that at least they are not participating. In the film of the New York show, the last person recorded cutting is a young man with a bit of a swagger who lustily shears off all that was left of Ono’s top so that she has to cover her breasts. He is heckled. But no one stops him. For the hecklers are part of the show. And, of course, the more people who cut, the easier it is to become a cutter. It must be O.K. Everybody’s doing it.

The first time I saw the Maysles film was at the Vancouver show (although it is online), and that was when I understood what the New York performance was about. A beautifully dressed Japanese woman kneels, offering no resistance, while a series of armed white people methodically destroy all her possessions. What is being represented here? Hiroshima. Nagasaki. The firebombing of Tokyo.

Ono had planned to spend only a few weeks in London, but she found the city’s art world receptive to her work. Interest spilled over into the non-art world when she and Cox released a film entitled “Film No. 4,” commonly known as “Bottoms.” Which is all you see: closeups of naked people’s bottoms as they walk.

Ono and Cox had filmed a six-minute version of the movie in New York, using a high-speed camera loaned to them by Maciunas (who had it on loan from someone else). In London, many art-world celebrities eagerly agreed to perform in it, and the final cut is eighty minutes long, at approximately twenty seconds of screen time per bottom.

But no one knows you’re a celebrity from the rear. So the film is not just a joke. There’s an edge to it. It mocks self-importance. Ono described it as “like an aimless petition signed by people with their anuses.” The movie was promptly banned by the British Board of Film Censors—about the best publicity a filmmaker could hope for in sixties London. It got Ono into the tabloids. By then, though, she had met John Lennon.

Their story—and it could all be true, who knows?—is that on November 9, 1966, the day before a show of Ono’s work was scheduled to open at Indica Books and Gallery, Lennon dropped in. The Indica was a short-lived countercultural art gallery (indica is a species of cannabis) whose patrons included Paul McCartney. Ono accompanied Lennon while he browsed the art on display. (She has claimed not to have known who he was, which is not very believable. It is believable that she did not care who he was.) One work consisted of an apple on a pedestal. Lennon asked her what it cost. She said, Two hundred pounds. He picked up the apple and took a bite out of it. She thought that was gross.

Another piece was a ladder. When you climb up, there is a magnifying glass, which you use to look at a piece of paper on the ceiling, where you read a tiny word: “Yes.” This was totally up Lennon’s alley. “It’s a great relief when you get up the ladder and you look through the spyglass and it doesn’t say ‘No’ or ‘Fuck you,’ ” he explained later.

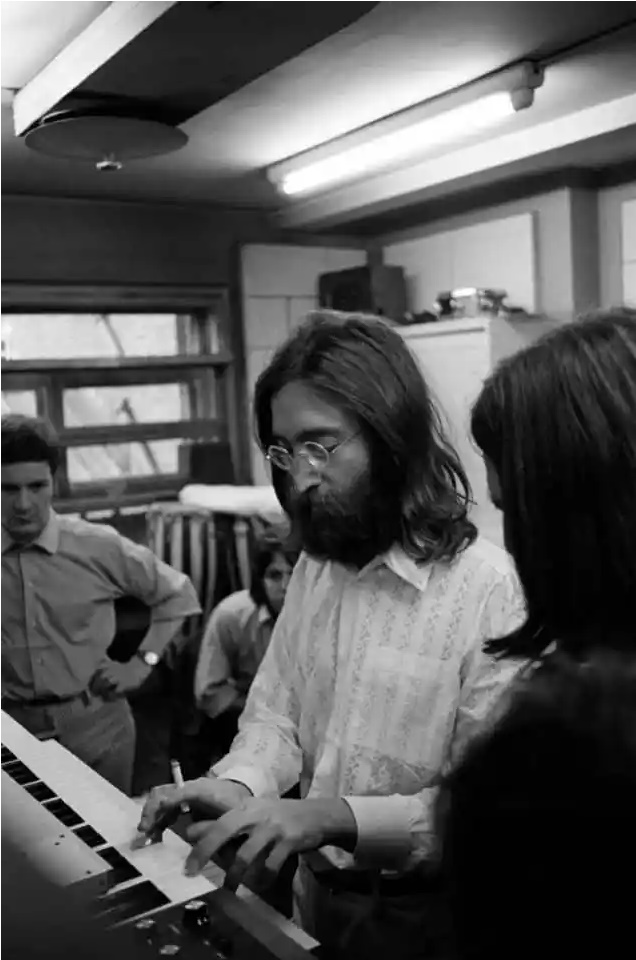

But they made their fateful connection with a piece called “Painting to Hammer a Nail In (No. 9).” Visitors are invited to hammer a nail into a board mounted on the wall. Lennon asked Ono if he could hammer a nail. Yes, she said, if he paid her five shillings. “Well, I’ll give you an imaginary five shillings,” he said, “and hammer an imaginary nail in.” “That’s when we locked eyes,” he said, “and she got it and I got it and, as they say in all the interviews we do, the rest is history.” For a while, they were “just friends.” It helps to remember that this was still very early in the Beatles’ career, less than three years after the band played “The Ed Sullivan Show” for the first time. They had not yet recorded “Sgt. Pepper.” Lennon had just turned twenty-six. Ono, on the other hand, was thirty-three. Her work had fully matured. She gave Lennon a copy of “Grapefruit,” which he read with attention. The affair did not begin until May, 1968. They went public in June, and for the next twelve years, until Lennon was killed, they lived under the constant scrutiny of the world press (another context for “Cut Piece”). Brackett says that Lennon was the clingy one, not Ono. Lennon made her sit next to him when the Beatles were recording, because he was afraid that if she was out of his sight she would leave him.

The Times music critic Robert Palmer thought that “having John Lennon fall in love with her was the worst thing that could have happened to Yoko Ono’s career as an artist.” Ono herself admitted that “together we hurt each other’s career and position just by being with each other and just by being us.” How true is that?

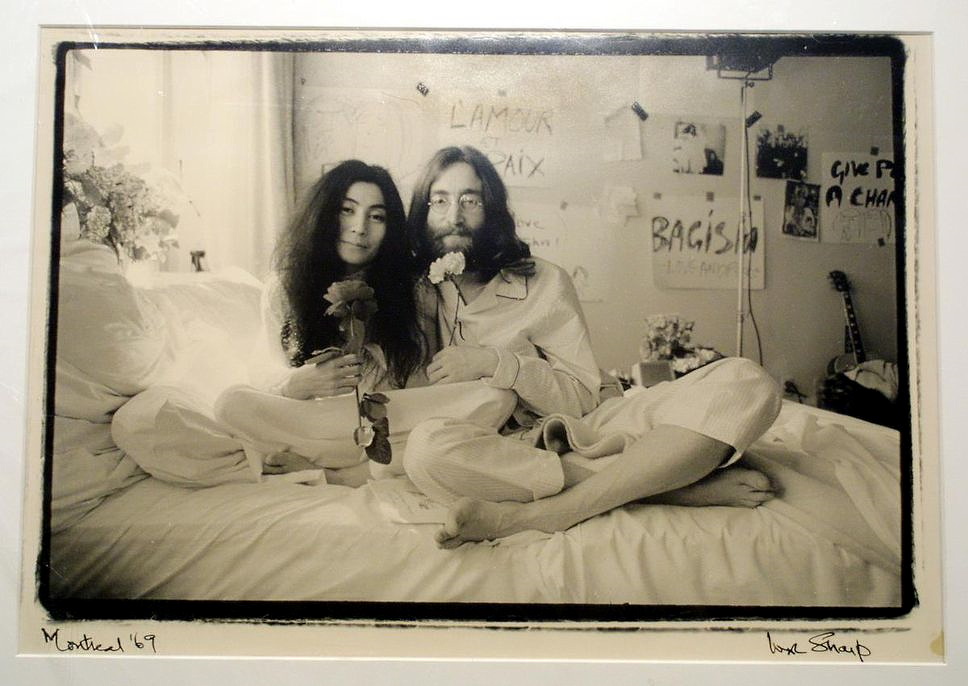

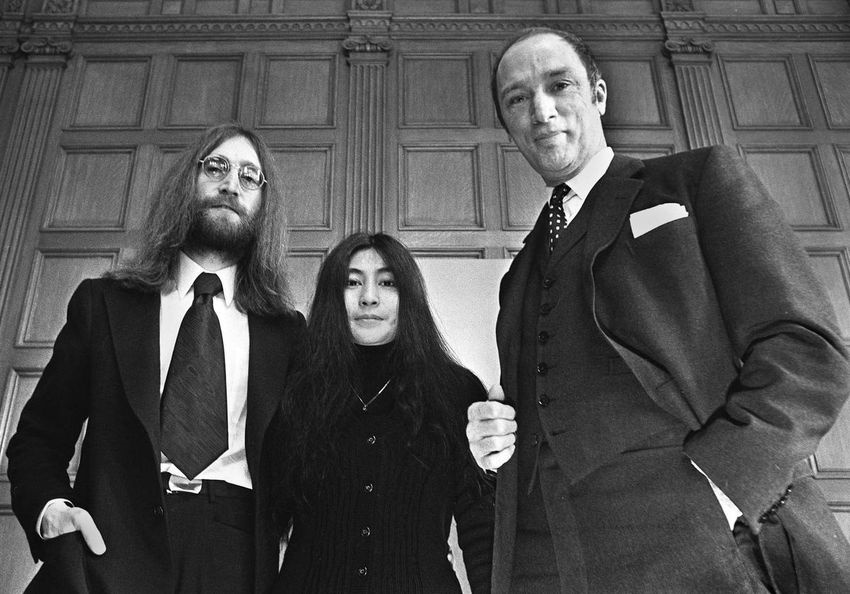

The Vancouver show covered Ono’s career from 1954 to the present, and the visitor feels an abrupt shift after 1968. Starting with the Bed-ins for peace, where she and Lennon sat in hotel-room beds in their pajamas and discussed politics with journalists and various counterculture celebrities, such as Timothy Leary, a lot of her work has been about world peace. It has also become explicitly feminist. Maciunas had a politics, but most Fluxus art—and Cage’s and Duchamp’s art—is apolitical. It is art about art. After 1968, Ono’s art is about politics. But that is true of virtually every artist. With the war in Vietnam, art got politicized, and it remains politicized today.

Ono’s conception of the audience for her work changed, too. When Ono and Lennon married, she was a coterie artist and he was a popular entertainer—maybe the most famous in the world. She performed for hundreds; he performed for hundreds of millions. She decided that condescension to popular entertainment is a highbrow prejudice. As she put it, “I came to believe that avant-garde purity was just as stifling as just doing a rock beat over and over.” So she became a pop star. Including the records she made with Lennon, she has released twenty-two albums. She expanded her audience.

Her music hasn’t sold the way Beatles music has, of course. But she and Lennon did produce one spectacularly successful collaboration.

“Imagine” was the biggest hit of Lennon’s post-Beatles career. The song was recorded in 1971, and, over the years, it has become a kind of world anthem, covered by countless artists, and played in the opening ceremonies at the Olympics and in Times Square on New Year’s Eve. Pretty much everybody can hum the tune.

It’s easy to enjoy the song and embrace the sentiments but to think of it as expressing a kind of harmless flower-power utopianism. That’s a misapprehension. “Imagine” is utopian, but it is also a work of conceptual art. It’s an instruction piece. “Imagine it in your mind,” as she told her little brother, had—improbably, but that’s the way culture works—ricocheted across time and space to end up, twenty-six years later, in the words of a song heard by millions.

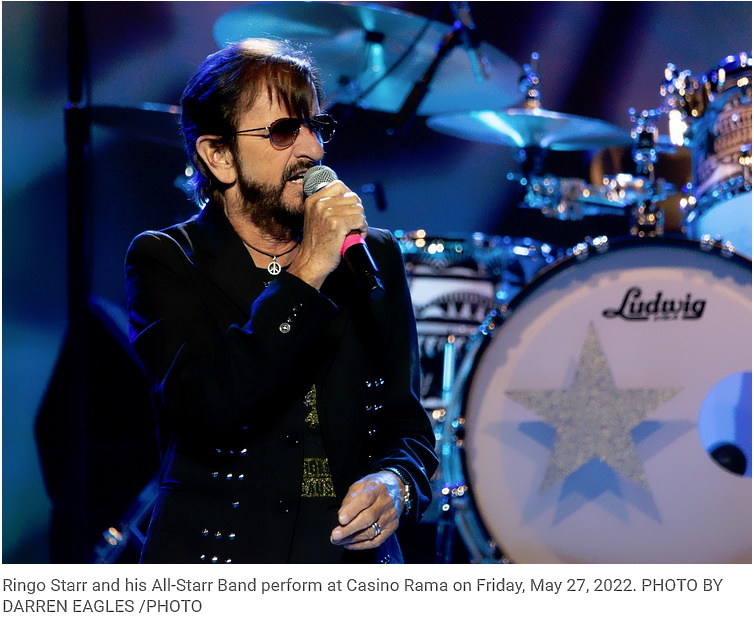

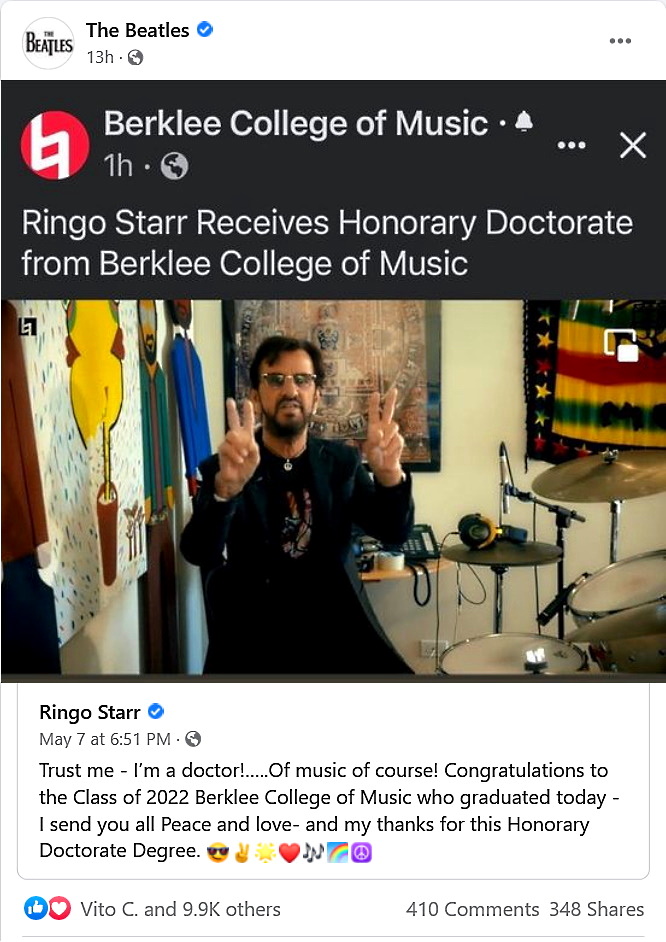

When the record was released, one of Ono’s instruction pieces from “Grapefruit” was printed on the back cover: “Imagine the clouds dripping. Dig a hole in your garden to put them in.” Later, Lennon said that it was sexist of him not to have listed Ono as a co-writer, given that the idea and much of the lyrics were hers. Somehow, though, he never did anything about it. But the world does go round, and in 2017 the National Music Publishers’ Association announced that, henceforth, Yoko Ono would be credited as a co-writer on “Imagine.” ♦  June 13, 2022 Covid 19 sidelines Ringo Starr and His All Star Band Tour

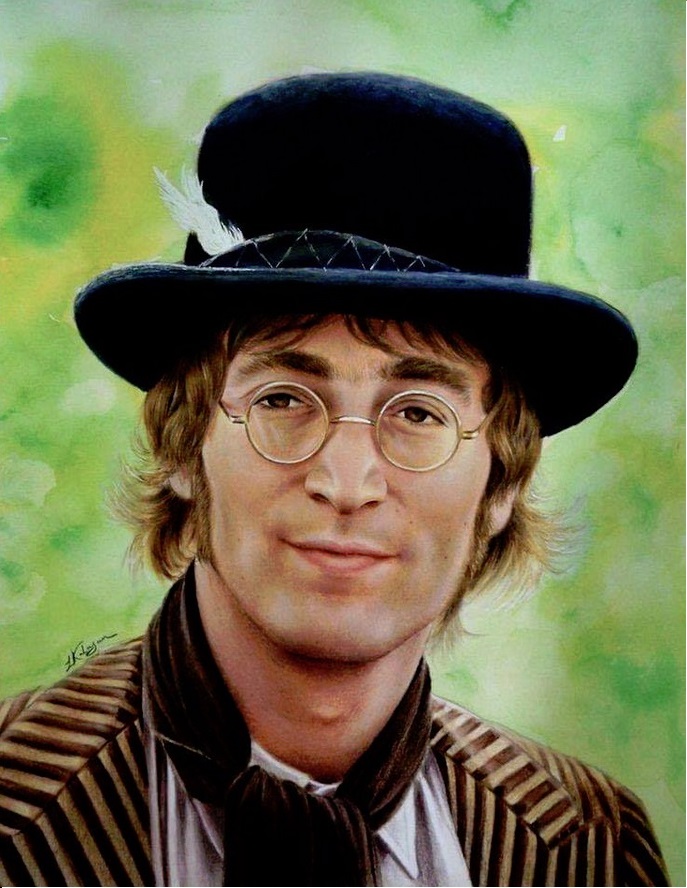

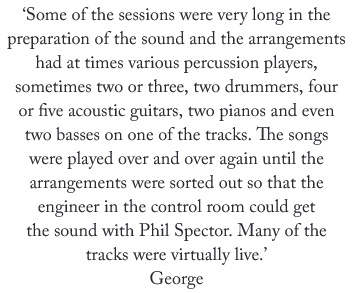

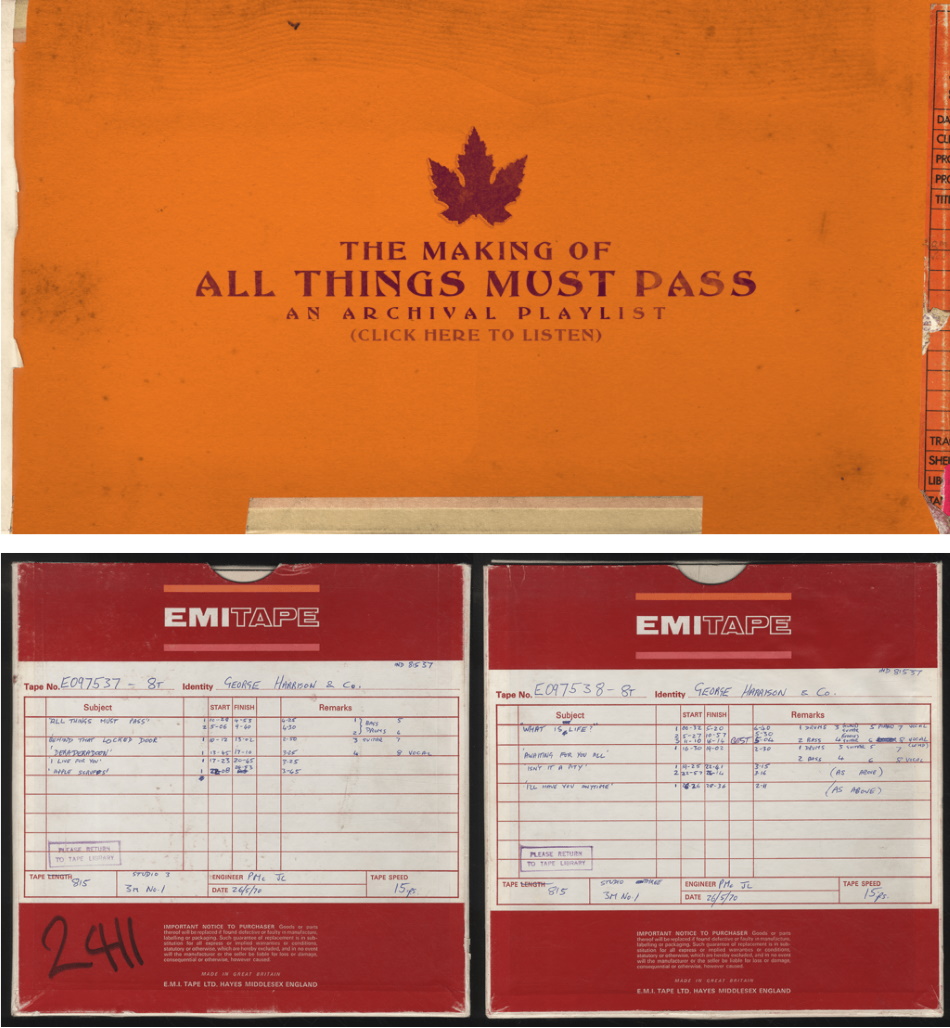

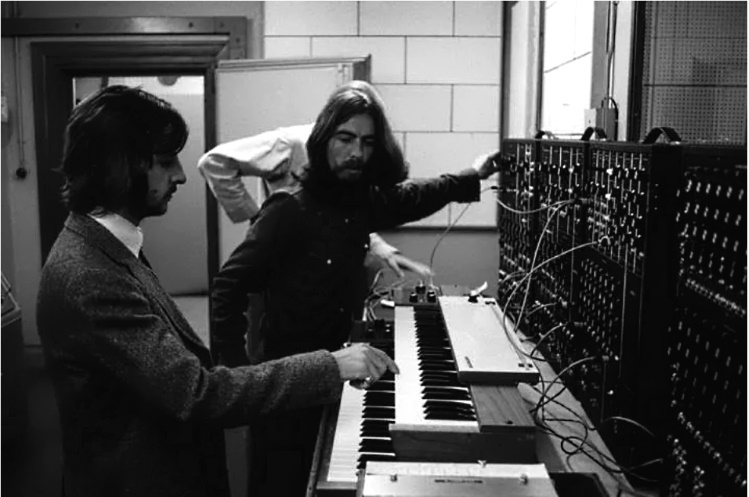

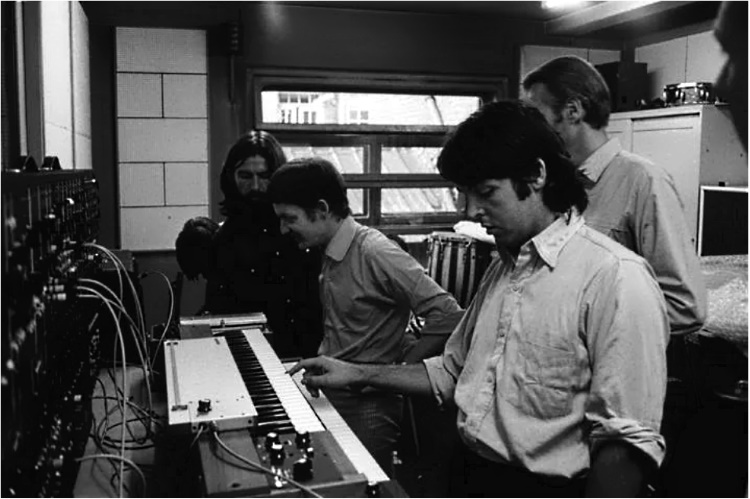

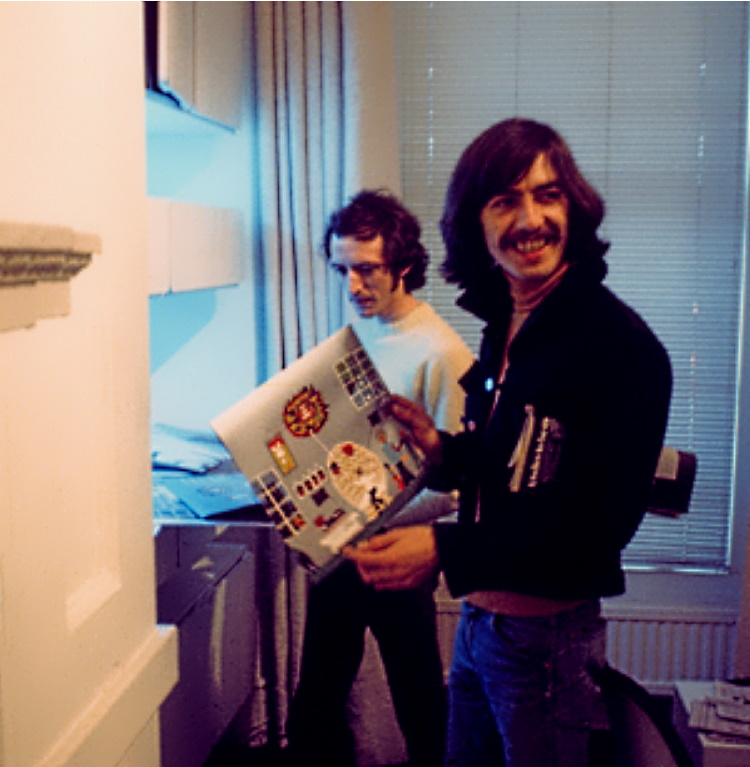

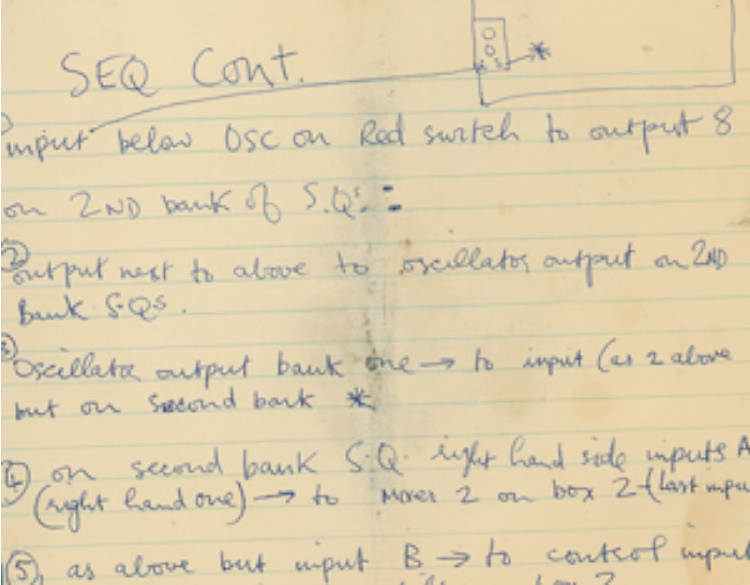

June 12, 2022 Archival session notes on the creation of "All Things Must Pass" The estate for George Harrison has put together session notes for "All Things Must Pass." "The session information is based on the original All Things Must Pass production notes, photographs and reel-to-reel session tapes in the George Harrison Archive," writes the estate for Harrison. The notes were researched by Don Fleming and Richard Radford. Below is part of the information provided, but the comprehensive report of the sessions is featured by clicking on this link: "ALL THINGS MUST PASS".

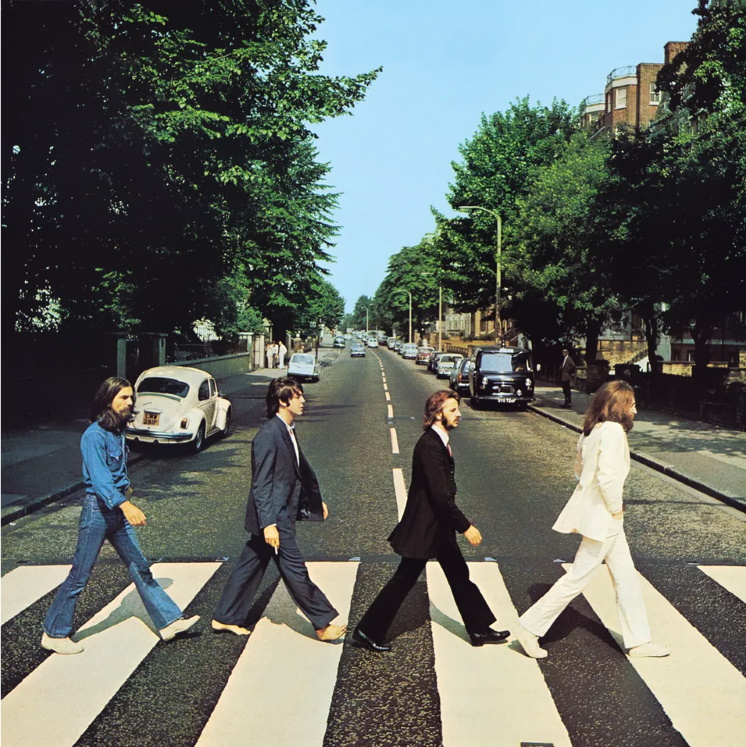

On Tuesday 26 May 1970, George Harrison entered Studio Three at EMI Studios, Abbey Road in St John’s Wood, London. To the public the studio was called Abbey Road, but for the engineers working there it was still EMI, until the name was officially changed in 1976. It had been George’s musical home since The Beatles first arrived there for an audition in June 1962. The Beatles are more associated with Studio Two, but had plenty of experience working in Studio Three. They had recorded songs for the Abbey Road album in Studio Three in 1969, including ‘Something’. George knew the room, and the engineers, very well.

George spent the first of two days recording thirty demos of songs that were being considered for his new, as yet untitled, album. There were recent compositions plus numerous songs that had been written during the past several years, but had not found their way onto albums or singles by The Beatles. There were also two co-writes with Bob Dylan, and two unreleased compositions by Dylan that George had learned directly from him.

George recorded fifteen demos on the first day with two of his oldest friends, Ringo Starr and Klaus Voormann. They were part of the studio team that George had assembled over the past two years for the albums on Apple Records that he had produced for Jackie Lomax, The Radha Krsna Temple, Doris Troy and Billy Preston.

On the second day, George recorded fifteen additional demos for his co-producer Phil Spector.

George had recently experienced Spector’s production style first-hand while playing on John Lennon’s ‘Instant Karma’ in January and then attending Spector’s mixing of The Beatles’ Let It Be in March and April. That album had just been released earlier in the month on 8 May.

The tracking sessions with the full band started on 28 May. Spector’s legendary ‘Wall of Sound’ required a large group of musicians to create an orchestra of rock instrumentation – multiple guitars, keyboards, basses, drums and percussion. George had a team of exceptional musicians to draw upon, his counterpart to Spector’s ‘Wrecking Crew’ in LA.

The mystery of who played on each track will will never be completely solved. The tape boxes from the sessions only indicate the instruments on each track, rarely naming the players. Some songs were recorded on more than one occasion, weeks apart with different sets of musicians, leading to contradictory accounts of the musicians on each song.

‘See, although the

album was done on an eight- track tape, and there

were some overdubs, most of those tracks had a lot

of musicians in the studio and it was done as Phil

Spector probably did his stuff back in the early

60s. That is to say it was routine that everybody

knew when they came in – with the piano, the

guitar solo, the tambourines – you just had to

learn it and do it as a take. So most of those

songs were done as a performance, really. And then

with the vocal, you had to do it again, or we’d

add the horns or strings, or whatever.’

Engineer Philip McDonald used the studio’s 3M M23 eight-track tape recorders and the TG12345 Mk I mixing desk throughout the session. McDonald had worked on sessions with The Beatles and had risen to become a top engineer at EMI Studios. This session would lead to Phil engineering and co-producing many of George’s solo albums.

‘I suppose I was a

whizz kid at that time. I was an in-house engineer

at EMI. I was supposed to do anything

that came through the doors. I think George must

have asked for me, but I can’t remember him asking

me personally.’

The session got under way with a big line-up: Eric Clapton and his new American pals from Delaney & Bonnie’s band: Carl Radle, Bobby Whitlock and Jim Gordon, along with George’s A-team: Ringo Starr, Klaus Voormann and Billy Preston, plus Pete Ham, Tom Evans, Joey Molland, and Mike Gibbons from Apple Records’ band Badfinger playing acoustics and percussion. But Spector wanted more: multiple pianos, more acoustic guitars, more drums.

‘It was just Spector

saying, “I think we need another piano,” so we’d

call in a pianist, or “I need another guitarist”

or “I need a percussion player”. But usually once

they’d started learning a song then they’d do that

one with the same people.’

Gary Wright from Spooky Tooth, Tony Ashton from The Remo Four, Peter Frampton and Jerry Shirley from Humble Pie, Alan White, who had played with The Plastic Ono Band at the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival festival and on ‘Instant Karma’ and would later join Yes, Dave Mason of Traffic, Gary Brooker from Procol Harum, and Delaney & Bonnie / Joe Cocker / Rolling Stones’ horn section Bobby Keys and Jim Price were all called in the tracking sessions. Maurice Gibb of the Bee Gees and a teenage Phil Collins spent at least one evening at Abbey Road playing on songs, though not on versions that were used on the album.

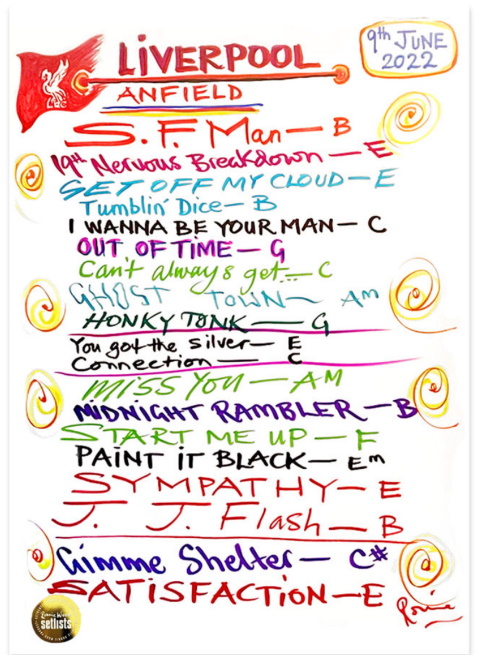

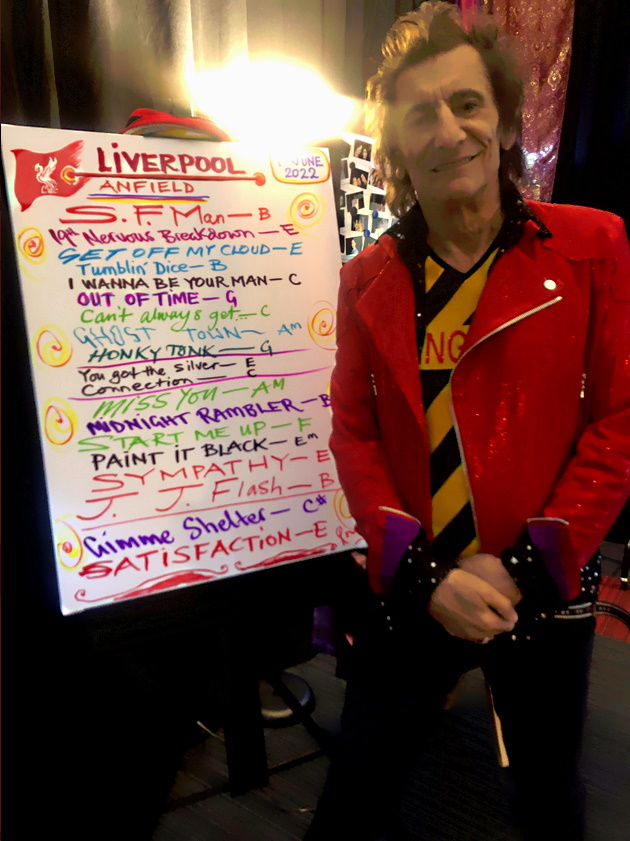

The arrangements for string and horns were written by one of George’s frequent collaborators, John Barham, and recorded at Abbey Road while George was doing overdubs in August, after the main tracking was completed. Abbey Road had been slow to install sixteen-track machines and George moved the sessions to Trident Studios in September to transfer some of the songs from eight-track to sixteen-track tape in order to create more open tracks for additional overdubs. The eight-track tapes were mixed at Abbey Road in early October and then the sixteen-track tapes were mixed at Trident, with the final mix completed on Saturday 17 October.  June 11, 2022 Watch The Rolling Stones Honor the Beatles in Liverpool With ‘I Wanna Be Your Man’ It marked their first performance of the 1963 classic in a decade, and their first time ever playing it in the Beatles’ hometown by Andy Greene for RollingStone

Added historical feature from the New Musical Express...

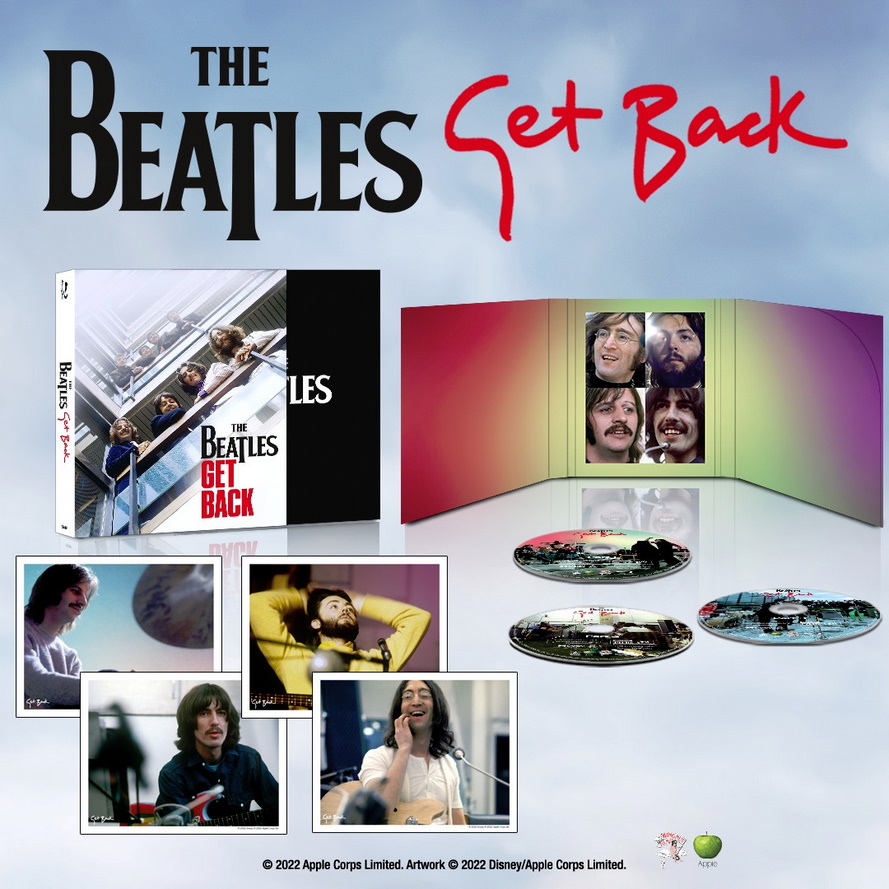

June 10, 2022 Just shy of 80, Paul McCartney goes back — all the way back The Beatle's first of a two-show stint at Fenway traced his career from his earliest days, but with no hint of slowing down. Paul McCartney may be feeling nostalgic, if not sentimental. For one of rock’s remaining forebears though, this can be hard to gauge. McCartney, who turns 80 on June 18, has been performing for well over three-quarters of his life in front of audiences in sweaty — and sometimes outright makeshift — venues in his native Liverpool and stadiums and arenas the world over. And despite his revered musical acumen that helped raise and push the second wave of rock ‘n’ roll to become a lasting and liberated art form, rather than a culture-shock blip fueled by teenage fantasy, too often overlooked in today’s rearview is McCartney’s sheer prowess for performance. Simply put, the guy knew — and still knows — what the fans want. Whether it’s what the man himself wants to play is altogether a different matter. Yet, there could be something a bit more personal, a bit more tender than just playing the hits behind Macca’s latest run — aptly named the “Got Back” tour, which pulled into Fenway Park on Tuesday and returns Wednesday night. Beatle buzz is common anytime McCartney or Ringo Starr hit the road. But this latest slate of shows — yes, they’re both currently on tour (Ringo just played the Boch Center last week) — comes on the heels of “Get Back,” the Peter Jackson-directed film released on Disney+ late last year, offering fans a fuller-picture of the band’s previously notorious sessions that would culminate in Let It Be. At Fenway on Tuesday night, McCartney rolled through a 36-song, career-spanning set, book-ended with Beatle classics “Can’t Buy Me Love” and the encore-closing “The End,” which capped off the medley fading out 1969’s Abbey Road. In between was a musical mosaic reminding us why McCartney remains one of the genre’s most colorful pioneers, laced with plenty of his distorted treble shouts and punctuated with his tactful “Yeahs” — outbursts forever reminiscent of an idol, Little Richard. When the band cracked open “Let Me Roll It,” from his Wings-backed 1973 release “Band on the Run,” McCartney strapped on a Les Paul to play the cutting guitar riff as if to prove he’s no octogenarian. And bolstered by his longtime and formidable backing band, McCartney can still hit those Everly Brothers- seasoned harmonies ever-present in his cataolog. When a sign by a fan wishing him an early happy 80th birthday caught his eye, he quipped, “Who’s that?” Indeed McCartney’s current setlist, stacked with a handful of more recent works — including “Fuh You,” off of 2018’s Egypt Station — shows he has no interest in being penned into the 1960s and ’70s. (Still globe trotting, McCartney is no Elvis in Vegas). And he’s well aware of what his audience thinks about that. “We can tell what songs you like,” he told the crowd late into his set, which ran just over two-and-a-half hours long. When Beatles hits fired through the speakers, out came a sea of phones from the audience, McCartney explained. He likened the view to a “galaxy of stars.” When the newer songs came out, though, there was a “black hole,” he said. “But we don’t care,” he continued. “We’ll do them anyway.”

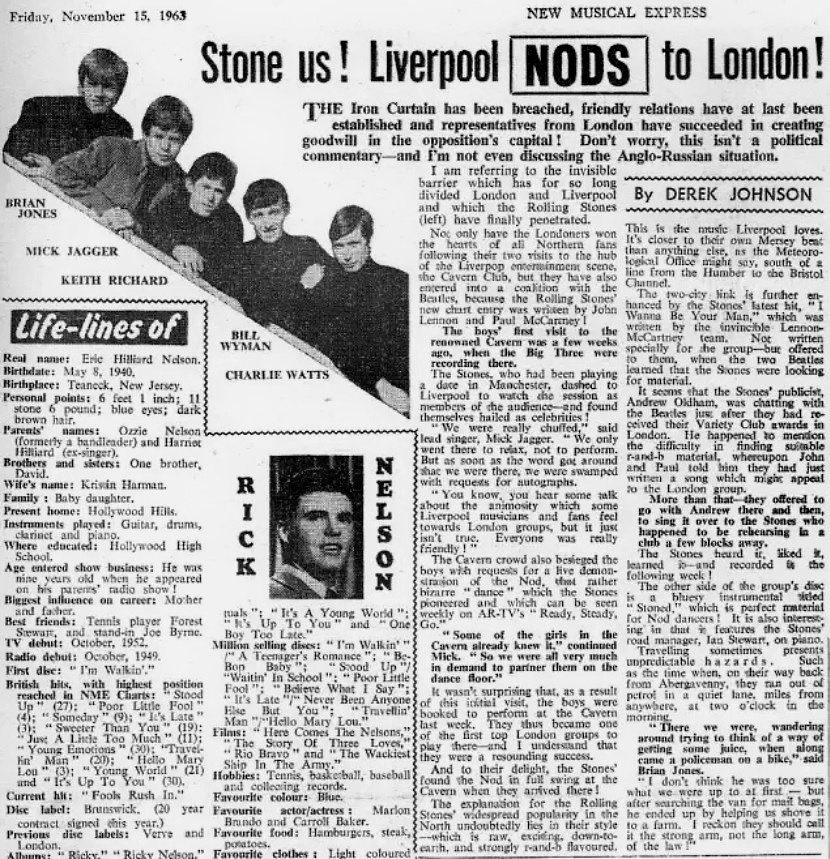

But it’s hard to shake a feeling that McCartney, now late in his life, is more acutely aware of his career’s glorious arc, or maybe just accentuating it a tad more. An undeniable living legend, McCartney has likely had to reckon with his public perception as an untouchable artist the likes of a modern Beethoven, rather than a boy who struck gold in a dreary, working-class city on England’s outer shores. “In that little port, there were these four guys who got together, formed a band, and ended up doing quite well for themselves,” McCartney told the crowd Tuesday. Next month marks the 65th anniversary of when a 15-year-old McCartney met John Lennon, joining the latter’s folksy, thorny, and completely homespun musical group, The Quarry Men. The following year, as McCartney explained, the five-member group that would someday shrink and evolve into the Beatles scraped together £5 to cut their first record, a lone 78 rpm disc the boys passed around by the week. (John “Duff” Lowe kept the pressing for some 20-odd years before McCartney bought it off of him, with Lowe making “quite a considerable profit,” McCartney quipped.) With a Martin acoustic guitar, McCartney brought back his boyhood as he played that track. Written with George Harrison, “In Spite of All the Danger” is an Elvis-heavy, adolescent plea to take on life’s toughest challenges — “anything you want me to” — for the sake of a relationship. McCartney’s mighty back-up band joined him downstage for the toned-down performance. Behind them stood a backdrop of a tin-roofed shack plucked out of 1950s southern America, suggesting a juke joint or front- porch affair that birthed the music that would roll into one large lump the Brits called “skiffle,” and hand the Beatles the match to set the world on fire with rock ‘n’ roll. At other times, McCartney, standing in Beatle boots, vest, and drainpipe pants, told stories about landing the group’s first recording contract and putting “Love Me Do” to tape, admitting he can still hear the nerves in his voice on the song’s solo refrain to this day. His late bandmates got nods with a ukulele-led cover of Harrison’s “Something” and a rendition of “Here Today,” the letter-in-song McCartney wrote to Lennon after the latter was killed in 1980. Offering some advice, McCartney told the audience to never pass up a moment to tell someone you love them.  When he wrapped “Maybe I’m Amazed” from McCartney, his first solo venture in 1970, McCartney pointed out an image of him and his then-infant daughter, Mary, that flashed above him on a giant monitor, taken from the album’s back cover. Mary, he said, now has four kids of her own. “How time flies,” he said with an air of disbelief not lost on the legions of grandparents that packed the house. “Maybe I’m amazed!” Living a lifetime in showbiz, McCartney is beginning to — finally — look a bit more his age, after all. His eyes are a bit more tired, though in year three of the COVID-19 pandemic, he’s certainly not alone. He’s embraced his grays more in recent years. He wears them well and they’re still a bit moppy. In the breeze at Fenway, it’s hard to not conjure a squint-and-you-may-see-it vision of the much-younger man who stood in the January chilly air on a London rooftop all those winters ago. Of course, with the Jackson film this past year, songs like “Get Back” have a renewed flair and remain dumbfoundedly accessible across the generations assembled in McCartney’s audience. And a late-set run of Beatles hits, from “You Never Give Me Your Money” to “Let It Be,” cranked up an electric jolt needed for the rather sleepy mid-week crowd that welcomed McCartney back to Boston on Tuesday. (Notably, however, signs spelling out “We love you Paul” wrapped the grandstand earlier in the night, causing the rocker to stop to “drink it all in for myself.”) Abundantly clear is that the beating heart of McCartney’s career will forever be that storied collaboration with Lennon — two friends whose ambitions and humor carried them into the stratosphere of stardom and have now shaped more than half a century of popular culture. Like the quintessential core of the “Get Back” sessions — intended to capture the band in a rootsy-er, less glammed-out version — it’s clear McCartney is not interested in myth making, but rather something more pure, more innocent, as the Beatles at their best will always be. His encore opener plays it straight. Using isolated vocals and video from the rooftop concert produced by Jackson, McCartney duets, virtually at least, with Lennon for the first time in decades on Let It Be’s “I’ve Got A Feeling,” with Lennon’s line “Everybody had a hard year” ringing a bit more true during this pandemic. “That’s beautiful for me,” McCartney said, summing it up afterwards. “Together again.” Perhaps even more fitting is McCartney’s full-throated bridge: All these years, I’ve been wanderin’ around Wonderin’ how come nobody told me All that I been lookin’ for was somebody who looked like you For a few minutes, together, the two boys from Liverpool sang across the ages, one on a screen high above and immortalized in long-haired youth, uncertain where that wild ride would take them all next. Below him stood McCartney, wearing all the life Lennon never got to embrace, but still left pondering about £5 recording sessions, a high school band, and the music he made with his friend. All these years, indeed. Setlist: 1. Can’t Buy Me Love 2. Junior’s Farm 3. Letting Go 4. Got to Get You into My Life 5. Come on to Me 6. Let Me Roll It (with Jimi Hendrix, Foxy Lady tribute) 7. Getting Better 8. Let ‘Em In 9. My Valentine 10. Nineteen Hundred and Eighty-Five 11. Maybe I’m Amazed 12. I’ve Just Seen a Face 13. In Spite of All the Danger 14. Love Me Do 15. Dance Tonight 16. Blackbird 17. Here Today 18. New 19. Lady Madonna 20. Fuh You 21. Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite 22. Something 23. Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da 24. You Never Give Me Your Money 25. She Came in Through the Bathroom Window 26. Get Back 27. Band on the Run 28. Let It Be 29. Live and Let Die 30. Hey Jude Encore 1. I’ve Got a Feeling (virtual duet with John Lennon) 2. Birthday 3. Helter Skelter 4. Golden Slumbers 5. Carry That Weight 6. The End Paul McCartney plays his second night at Fenway Park on Wednesday, June 8.  June 9, 2022 1962 Was The Final Year We Didn't Know The Beatles. What Kind Of World Did They Land In? The Beatles broke out regionally in 1963 and nationally in 1964, which makes 1962 the last year they weren't widely known. And given that we'll probably never forget them, that makes it a special year indeed. What was going on then? by Morgan Ends for the Grammy Awards

During the mid-to-late 1950s, the titans of rock 'n' roll dominated the earth; by 1962, many of them had seemingly gone extinct.

Buddy Holly went down, young. Little Richard found Jesus. Jerry Lee Lewis married his 13-year-old cousin and was crucified in the press. Chuck Berry spent three years in jail. Elvis, fresh out of the army, was making films often derided as beneath him. So when the Beatles broke out — regionally in 1963, and nationally the following year — they arrived in a barren, joyless world, right?

This is usually the line: In the wake of the Kennedy assassination, in a wasteland of schmaltzy, insipid crooners, the Fabs made the desert rejoice and blossom as the rose. As a gang of impudent, talented youths — a feast for the ears and eyes — with reams to give the world, they taught an unmoored and grieving America to have fun again.

Of course, that certainly applies to some Americans in those days. But if you ask Mike Pachelli, he might give you a different story. Because he was there.

Indeed, it's tempting to frame the Beatles as messianic — reams of ink have made their debut performance on "The Ed Sullivan Show" to reinforce that narrative. Everybody remembers "All My Loving," "She Loves You" and the rest; few remember that they were followed by a desperate-looking magician doing salt-shaker tricks. (As Rob Sheffield put it in Dreaming the Beatles: "Acrobats, jugglers, puppets — this is what people did for fun before the Beatles came along?")

Through that lens, the Beatles can look like the product of divine intervention, meant to restore brilliant hues to a monochrome culture, Wizard of Oz-style. Why not ask Tune In author Mark Lewisohn about it? He's almost universally regarded as the foremost global authority on the Fab Four. And to that point, he lists some names.

"Otis Redding, James Brown, Little Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, Paul Simon, Freda Payne, Randy Newman, Ike and Tina Turner, the Supremes, Wilson Pickett, Gladys Knight, P.J. Proby, Barbara Streisand, Glen Campbell, Patti LaBelle, and Dionne Warwick" were all waiting in the wings or as established stars in 1962, he tells GRAMMY.com.

"They're all making records before the Beatles," Lewisohn continues. "So, anyone who says the Beatles fashioned the entire scene doesn't know what they're talking about." Rather, the Beatles entered an already-fecund landscape 60 years ago — and reshaped it forever.

Humming a song from 1962

In the grand pop-cultural timeline, 1962 tends to represent innocence, youth and the "good old days." In his 1976 hit "Night Moves," Bob Seger awakens "to the sound of thunder," with a song from that year on his lips. (It was the Ronettes' "Be My Baby," which was actually from '63; apparently, Seger felt strongly enough about what 1962 meant to him to tweak history a tad.)

Plus, George Lucas didn't set his classic coming-of-age flick American Graffiti in 1962 for nothing.

"These kids are driving all night and they're hearing the '50s rock 'n' roll on the radio," Sheffield, who is also a Rolling Stone contributing editor, tells GRAMMY.com of the 1973 film. "They're listening to Wolfman Jack and it's kind of the last gasp of that old school rock 'n' roll era."

Sheffield cites the scene where a brooding John Milner (played by Paul Le Mat) tells the gangly, 12-year-old Carol Morrison (played by Mackenzie Phillips) to turn off "that surfing s***" on the dashboard radio — the Beach Boys' "Surfin' Safari." "Rock 'n' roll's been going downhill ever since Buddy Holly died," Milner reports, his face fallen.

American Graffiti's soundtrack is packed with hits that paint a picture of young love in Modesto, California, in 1962. Aside from '50s jukebox mainstays like Bill Haley and the Comets' "Rock Around the Clock," you've got obscurer cuts by acts like Lee Dorsey, the Cleftones, and Joey Dee and the Starlighters — all from the previous year.

If you want to understand the prevailing vibe of the year in question, American Graffiti is the first looking-glass you should peer through. For another, look no further than the Beatles' infamous audition for Decca Records — on the very first day of 1962.

"Searchin' Every Which A-Way"

The Beatles had a massive, unlikely shot on January 1, 1962, when they auditioned for Decca Records. But by most accounts, they blew it: the label ended up telling them "guitar groups are on their way out." (They ultimately went with Brian Poole and the Tremeloes.)

The Decca audition, which floats around the internet today, is famously regarded as terrible — John Lennon called it "terrible" himself a decade later. But if you listen today with fresh ears, it's really not — despite some rough moments and pre-Ringo drummer Pete Best's shaky grasp of rhythm.

It's important to note that the Beatles weren't experimenters come 1965 with Rubber Soul, or with 1966's Revolver — they were a deeply experimental band from jump. The Beatles were unique for their ability to emulate and synthesize disparate threads of 1962's musical landscape; just take a look at their Decca setlist: Immediately notable are Lennon-McCartney originals like "Like Dreamers Do," "Hello Little Girl" and "Love of the Loved," which was unheard of — rock 'n' roll groups simply didn't write their own songs back then.

On top of that, you've got a Phil Spector ("To Know Her is to Love Her"), a showtune via Peggy Lee ("'Til There Was You"), a jolt of Detroit R&B ("Money (That's What I Want)"), comedic numbers (three Coasters songs, including "Searchin'"), a jazz standard (Dinah Washington's take on "September in the Rain") — on and on and on. All of that, plus country and western, music hall, and so many other forms, were swimming around their skulls.

"What they'd been doing in Hamburg and then brought back to Liverpool was 'We just have to do everything, because we're playing for 10 hours a night,'" Alan Light, a music journalist, author and SiriusXM host, tells GRAMMY.com. "Anything that they knew, or anything that they might know, was fair game for material, because they just had to keep going."

But the Beatles' omnivorousness in this regard, both in their choice of cover material and raw inspirations for songs, wasn't just to run the clock — it spoke to their essences as artists and human beings. "They were so receptive to anything that was good, and it didn't matter what genre it was, as it didn't matter what genre they were," Lewisohn says.

So, how do you know that music in 1962 was, in many ways, outstanding? Because without it, there'd be no raw material for the Beatles to work with.

Aside from the Beatles' purview, other fascinating musical forces were at play. According to Kenneth Womack, a leading Beatles author, what the music industry hawked in 1962 wasn't necessarily what the public asked for — hence John Milner's reaction in American Graffiti.

"What happens is you go from that pretty intense rock era to the crooners and doo-woppers coming back with a vengeance," Womack tells GRAMMY.com. "That was really not music that people wanted. It was music that was marketed to us."

Still, many tunes from 1962 and thereabouts endure — including all the tremendous, often Black, talent Lewisohn mentions above, as well as a smattering of bubblegum songs that have baked themselves into 21st-century life.

That year, Shelley Fabares released her confectionary cover of "Johnny Angel," and Chubby Checker's "Let's Twist Again" won a GRAMMY for Best Rock 'n' Roll Recording. The Tokens’ "The Lion Sleeps Tonight" became a No. 1 hit; so did Gene Chandler's "Duke of Earl." ("There's still a pulse around the old-world stuff," Light notes about the latter tune. "It's not gone.")

Plus, recent years had given us "Itsie Bitsie Teeny Weeny Yellow Polkadot Bikini" and "The Purple People Eater" — further proof of novelty songs' enduring presence.

"It's funny that the song from 1962 we hear the most nowadays might be 'Monster Mash,' which has just turned into such a seasonal banger," Sheffield says. "If you went back to a music fan in 1962 and said, 'Sixty years in the future, the most famous song from this era is going to be 'Monster Mash,' people would laugh in your face."

"You've got a lot of the trivial pop throwaways that the people laugh about, but a lot of those were fantastic songs," he continues, citing rock 'n' roll singer Freddy Cannon's "Palisades Park" as a "fan-f***ing-tastic song": "The drummer on that song is absolutely insane. That's the year that Stax starts to make its mark nationwide."

On top of that, you've got Spector, Motown, Chicago soul, Memphis instrumental R&B (hello, Booker T. and the MGs' "Green Onions"), the still-green Beach Boys and Bob Dylan… the list goes on. To say nothing of Ray Charles, whose Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music — released in 1962 — remains a monumental fusion of Black and white cultures.

1962 was also a major year in American culture: John Glenn became the first man to orbit the Earth, the Cuban Missile Crisis erupted, and it was the only full year John F. Kennedy was president. The Space Needle and the first Wal-Mart were opened. Marilyn Monroe sang "Happy Birthday" to JFK and died three months later.

In British media at the very least, there was a shift toward irreverence that left an opening for the flippant and cheeky Fabs. "The Beatles came up at the very same time when you could be less respectful to the sacred cows of society," Lewisohn says, noting a rising acceptance of unfettered working-classness, like in the pre-"Sanford and Son" show in the UK, "Steptoe and Son."

Sheffield stresses the impact of the draft on the world the Beatles entered: "I think they presented to American youth a vision of adult male life that wasn't military-based or violence-based," he says. And across the pond, the abolition of conscription in the UK in 1959 had fundamentally shaped the Beatles' path.

"They were clearly not boys who had been in the war," Lewisohn says. "The Beatles escaped it in the very nick of time."

What If The Beatles Never Broke Through?

As most parties agree, one of the weirdest things about the Beatles is that they happened at all — which is easy to overlook due to their sheer omnipresence.

"For me, the weirdest things about the Beatles are the most obvious things about the Beatles. Just the four of them being born in this town and finding each other and making music together," Sheffield says. "It's so shocking and bizarre that that synchronicity happened and that they were as good as they were, and they were able to keep inspiring and challenging and goading and competing with each other, and that they were able to scale those heights."

"I mean, there's nothing in world culture that's anything like a precedent for this," he continues. "And they were able to do it for 10 years, which is about 30 times longer than anybody would have predicted in 1962. That in itself is so completely bizarre."

Not that anyone could be a prognosticator — but if the Beatles had never been born, or broke up when they began, what would the '60s be like? Obviously, the Vietnam War and subsequent youth revolt would happen. Humanity would land on the moon.

But the music world, including all their peers, would be radically different. Without them, the Stones would probably never have written songs, or had their manager. The Beach Boys wouldn't have been spurred to make Pet Sounds or "Good Vibrations." The Byrds wouldn't use a 12-string Rickenbacker (Roger McGuinn got it from A Hard Day's Night), nor spell their name with a y. Bob Dylan may have never broken out of the folk scene.

Without the Beatles, the template of a self-contained band — a democratic gang with a unified message, lobbing working-class Britishness into the world, raining down heartening music and blistering humor, and reinventing themselves seven or eight times before drawing the blueprint for band breakups — would be gone.

"I feel like rock 'n' roll would've come back," Colin Fleming, who writes articles and books about the Beatles, tells GRAMMY.com. "It's almost like someone's on the injured list on the baseball team."

But everything played out how it did — and what unending pleasure and edification. Still, history screams that the decade would have remained semi-recognizable without the Beatles.

The '60s would still be action-packed, just in a different way; it contained all the nascent threads and forces to be so. In 1962, you had the debuts of James Bond, Spider-Man and "The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson." Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange was published. Lawrence of Arabia opened in cinemas. America's presence in Vietnam dramatically escalated.

"The more I thought about it, October of '62 is interesting," Jordan Runtagh, an executive producer and host at iHeartMedia, tells GRAMMY.com. "That's the month that 'Love Me Do' came out. On the same day, Dr. No came out. It's the same month that Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? came out, which completely revolutionized the theater."

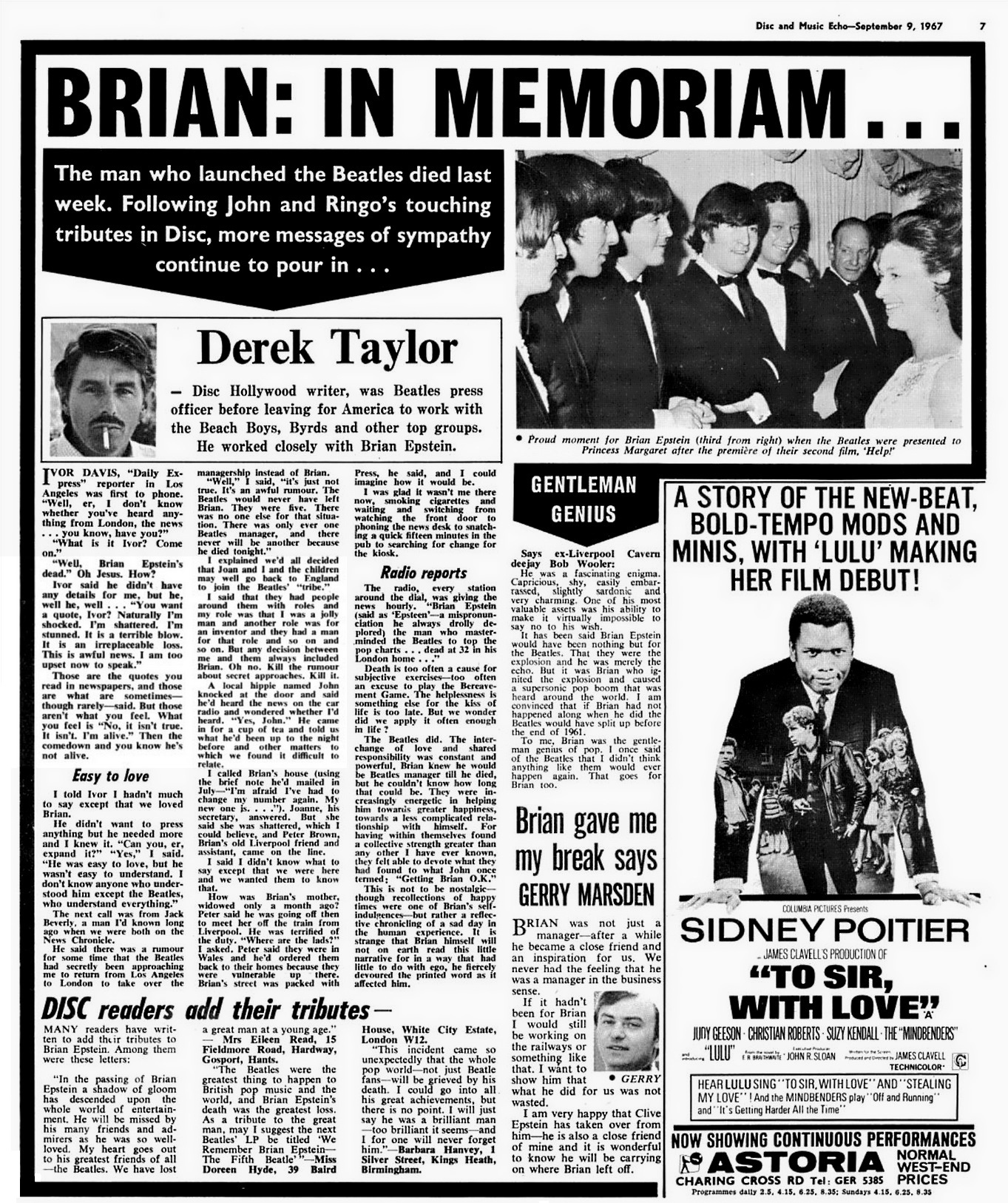

It's easy to consider the '60s without the Beatles as unthinkable. But even as a diehard fan, the thought is actually strangely beautiful. Flashback: Derek Taylor writes on the passing of Beatles Manager Brian Samuel Epstein

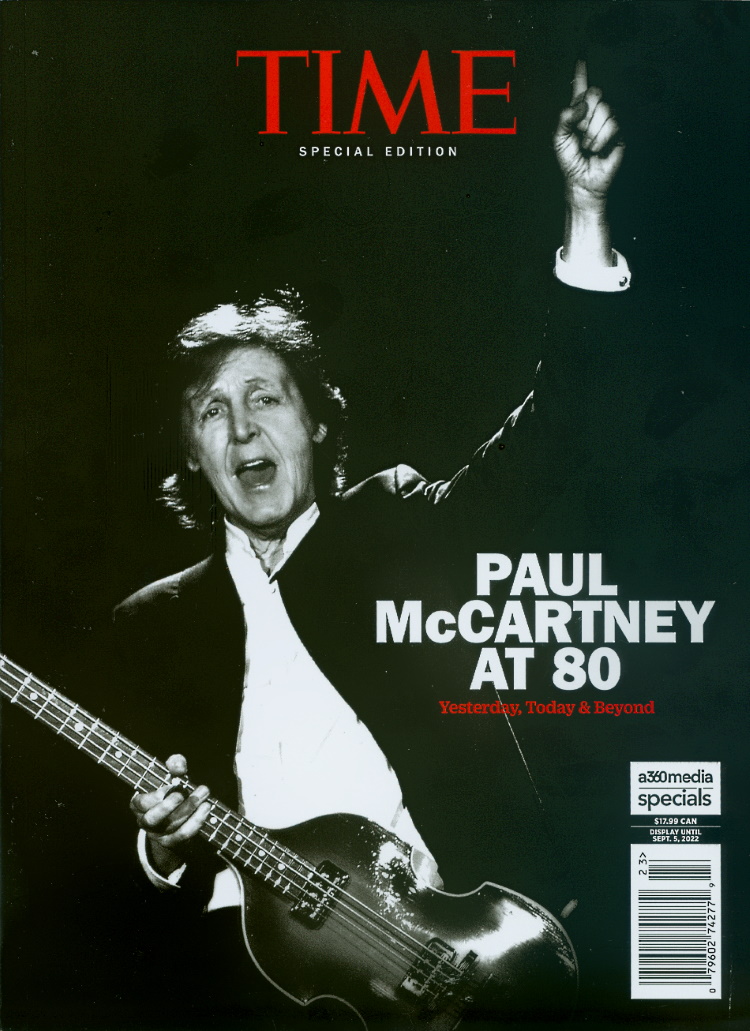

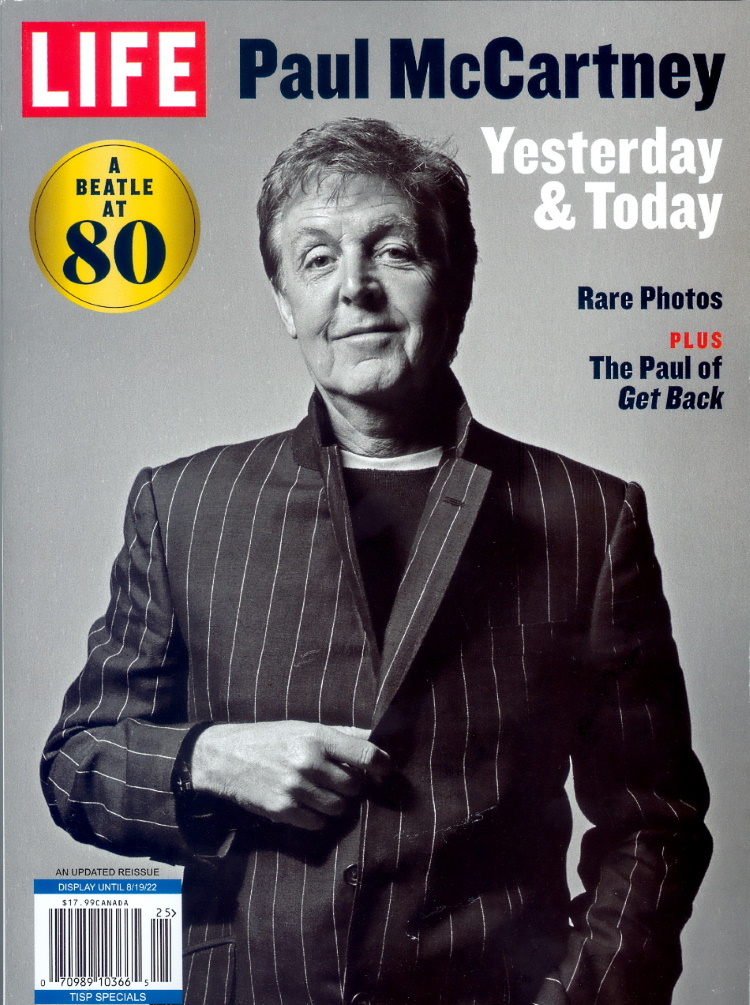

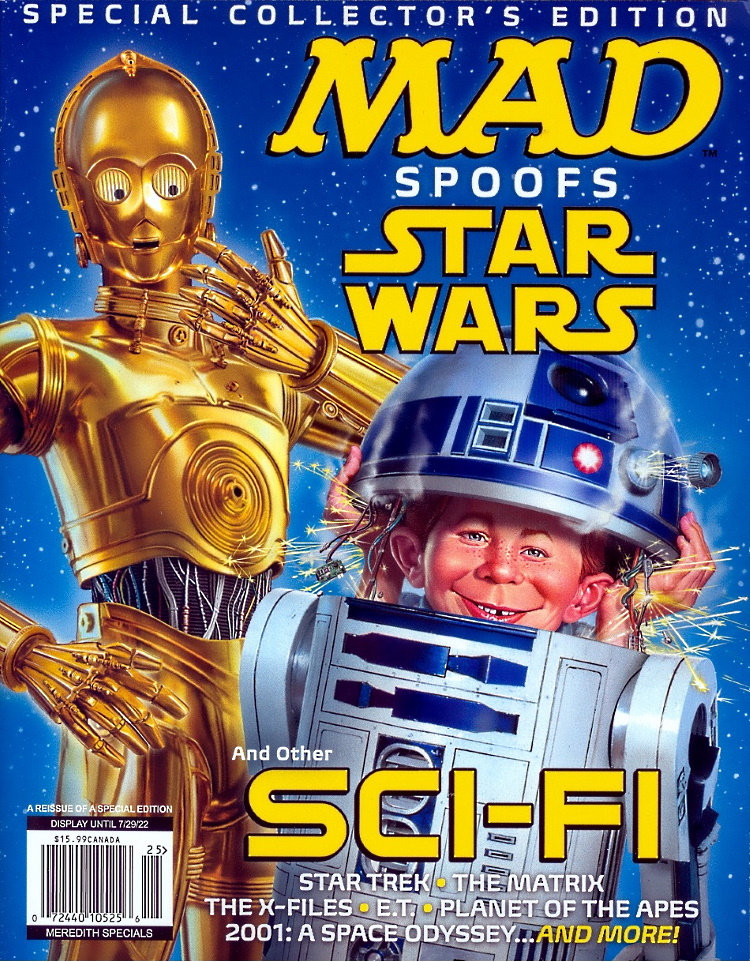

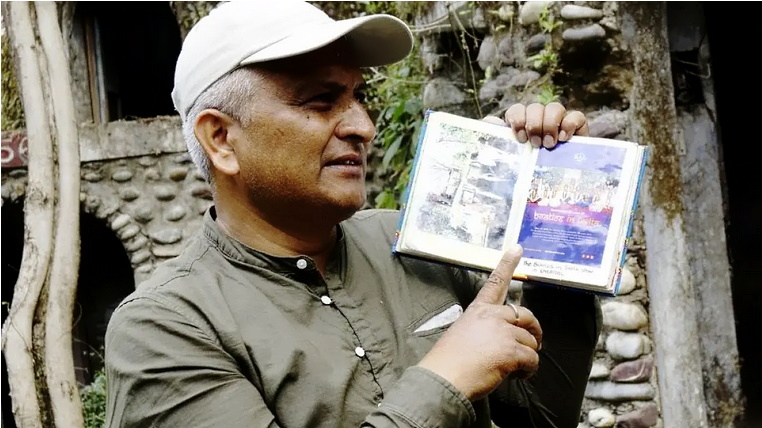

June 8, 2022 Today it was a hat trick on Special Magazine Editions At Shoppers Drug Mart I purchased three collectable magazine editions: Two of them on Paul McCartney from Time and Life. And the third one from Mad magazine with various spoofs on Star Wars, Star Trek, The Matrix, Planet of the Apes, etc. ─ John Whelan, Ottawa Beatles Site

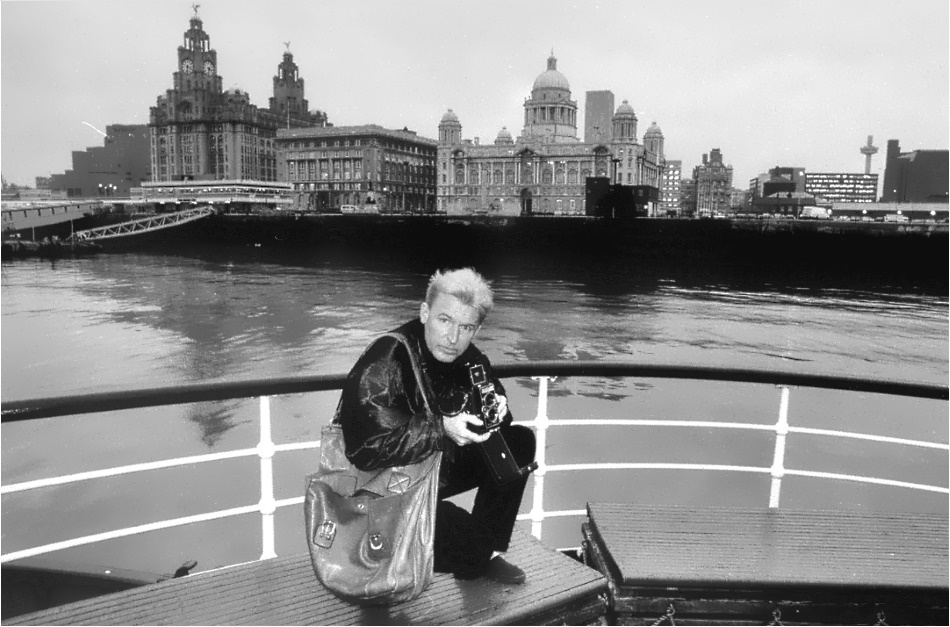

June 7, 2022 Paul McCartney’s Brother Recalls the Beatles’ Early Years The photographer reflects on 1962, a watershed year for his brother's band by Jeff Slate for InsideHook

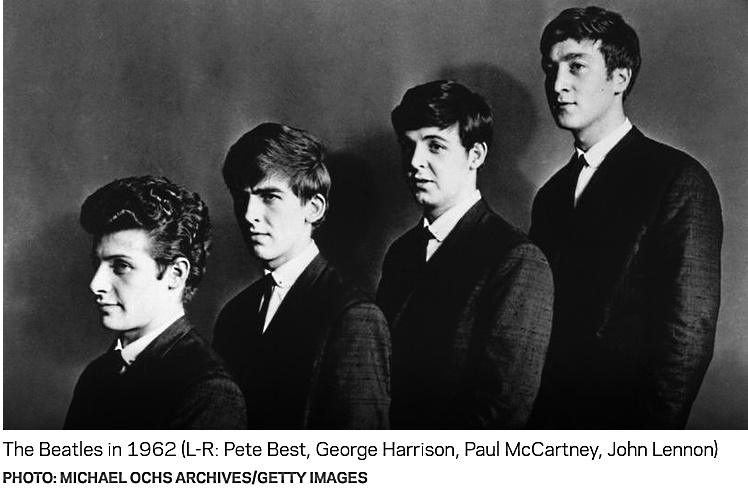

On June 6, 1962, 60 years ago this week, the very nervous, almost-Fab foursome of John, Paul, George and Pete entered EMI’s studios on Abbey Road in the St. John’s neighborhood of London for their first recording session under the recording contract that the already legendary producer George Martin had offered their rather green manager, Brian Epstein, on the label he was then managing, Parlophone, when the pair had met the previous February. But the group — who were tearing up the pub and club circuit in the north of England after a long, grueling stint in Hamburg, Germany, where they’d played eight hours a day, six days a week, honing their craft and becoming one of the tightest and rawest bands in the country — nearly didn’t make the cut during that first session.